Chad Michael Morrisette is surrounded by bodies. They crowd his West Hollywood home, which also serves as headquarters for his window-dressing business. Dismembered limbs are piled on shelves and boxes, and mannequin torsos are suspended with rope in his backyard. Morrisette’s collection is overwhelmingly female, so when Sony Pictures approached him to find a mannequin to tour its Spiderman costume last summer, he embarked on a difficult search.

“I kept showing them male mannequins, and they were like, ‘That’s not a superhero pose. That’s not strong enough. Spiderman doesn’t stand with his arms folded. He doesn’t stand with his hands on his hips,’ ” says Morrisette. “I was able to find one where the chest is a little bit puffy, and the head is up, and it’s a little bit more heroic in its posing.” The winner, a muscular golden statue, was subjected to some cosmetic surgery; nipples were shaved off and the ears cut in order to fit the costume.

This dilemma typifies the nature of the rarefied mannequin world, which is highly feminized. Mannequin manufacturers produce fewer male than female mannequins overall, which means there’s a more limited range in appearance. Although body diversity campaigns have sought realistic makeovers for female mannequins, male mannequins have escaped similar scrutiny. This is not only because there are fewer of them; it’s also because there’s less at stake. The cultural norms that impose stereotypical physical ideals on women don’t exist for men. Images of portly guys, or men built more like saplings than tree trunks, exist in popular culture without question or criticism—from Homer Simpson to Marty McFly. Mannequins, however, still embody a social history of masculinity and male physicality. While the ideals inscribed into the bodies of male mannequins are not enforced by the same structural sexism that enforces standards of female beauty, male mannequins do signify evolving notions of manhood.

The History of (Man)nequins

The first mannequin was born as a man—or, at least, as a rough approximation of a male body. Mannequins emerged in the 18th century as dolls called “lay figures,” which were used in artists’ studios in place of live male models. The very word “mannequin,” is derived from a French term meaning “little man.”

In Cutting a Figure, textile and fashion historian Alison Matthews David traces in her thesis paper the evolution of mannequins from artists’ dummies to full-bodied male forms. “The word began its metamorphosis during the early 19th century: the term mannequin was stylish men who advertised the wares of tailors, then to the anthropomorphic dummy who began to replace this male model in the clothing industry,” writes David.

Mannequins in the late 1700s and early 1800s were largely faceless and generic, and their torsos were broad and flat. One of the first known mannequins was a 2-foot-tall lay figure composed of a cork body, wooden head, and hinged limbs that fell limply at the sides. “This physical malleability made the mannequin a symbol of moral passivity,” writes David. The word ‘mannequin’ was inscribed with class and gender connotations—people began lobbing it as an insult, to describe fashionable men of leisure who lacked a certain moral fiber and strength of character. A feminine, foppish quality was implied by the slight.

It wasn’t until the 1820s that mannequins began developing more human-like bodies. The Industrial Revolution marked a turning point for fashion—the manufacture of large panes of glass eventually gave birth to the modern window display. As the window display became an integral part of urban pedestrian life, it wasn’t long before tailors began using mannequins to exhibit and advertise their wares. Upper-class men in particular favored the use of mannequins as tailors’ dummies. “The intimacy of the tailor’s touch collapsed the physical distance that rank and social position placed between him and his clients,” writes Davis. “The dummy soon came to aid the tailor in his task and obviated the need for such direct contact.”

These proto-mannequins were made of plaster and extremely heavy. Marsha Bentley Hale, a mannequin historian who began her career photographing the forms in 1970s Los Angeles, London, and Paris, says they also forged mannequin men out of wax, complete with papier-mâché heads and fitted glass eyes, the hair applied with a hot needle. “Often, the male mannequins would look somewhat effeminate because ... they would use makeup [to draw on their faces],” says Hale.

It was around this time that the first female mannequins began appearing. David attributes this gender shift to a Parisian tailor named Alexis Lavigne, who began casting custom molds of the human body. Lavigne soon opened up a women’s tailor shop where he sold women’s horse-riding habits. He featured his female mannequins in advertisements for his tailoring services, and these images reinvented the mannequin as not only a clothes hanger but also a fashionable model on which women—and men—could project desires. As corsets became popular in the 1840s and ‘50s, female mannequins acquired pinched waists and curvier figures. With more control of the household purse strings, women were becoming more active consumers of fashion, and shops were looking to capitalize on this. By the turn of the 20th century, female mannequins completely dominated shop window displays.

Modern (Man)nequins

The male mannequins of the early 1900s didn’t look all that different from their female counterparts. They were almost ghoulishly life-like, with false teeth, glass eyes, and human hair. The Art Deco era produced male mannequins with exquisitely stylized heads; jovial expressions were often sculpted into their faces, perhaps in homage to the roaring ‘20s. These mannequins had slim torsos and jointed limbs, which allowed them to be posed as though they were riding on bicycles or dancing. The era brought a sense of dance and movement to mannequin staging as well. “As you get into the 1920s to the early 1930s, you started having mannequins that were a little more athletic,” says Hale. “There was more attention, more detail, in the physical fitness of the male mannequin.”

In 1929, Wall Street had crashed, precipitating the Great Depression. Men felt emasculated by their inability to fulfill their traditional roles as family breadwinners. Masculinity, and especially American masculinity, was in crisis. Popular culture became flooded with images of brawny, working-class men in an effort to rehabilitate the American male ego and encourage a return to the workforce. Mannequin faces lost their smiles, and their expressions became somber and subdued. By World War II, they had acquired soldiers’ bodies, with postures that stood at attention. “The war did change things,” says Morrisette, who owns mannequins from the era. “You definitely can see the more puffed-up masculine mannequins.”

By the 1940s and ‘50s, a social and political conservatism had taken hold of American society. This conservatism manifested itself in shifting notions of masculinity. The nipples of older male mannequins were shaved off. Their smiles became more restrained. Some of their faces had holes where display artists would insert pipes. “[They] were almost cartoon-like, like Father Knows Best,” says Hale, referring to the popular TV show that ran through the 1950s starring the genial Robert Young. Like Young, these mannequins were dressed in tweed jackets and bow ties, the picture-perfect representation of middle-class American family dads. They were, without exception, always white.

The American Dad had become an outdated conception of masculinity only a couple of decades later. The 1960s saw the flowering of the civil rights movement; the 1970s saw the tragedies of the Vietnam War produce a generation of men disaffected with traditional notions of manhood and expressions of patriotism. Male mannequin faces of this era became exceedingly expressive, roaring with unheard laughter.

“In the ‘70s, they even made mannequins with faux chest hair. You could buy them with this hairy effect on them,” says Morrisette. The mannequins also reflected the relaxed and liberal sexual codes of conduct of the time. “Some of them were made to wear swimming trunks. They had what they called ‘the basket,’ which kind of made them look like they were rather well-endowed,” says Hale with laughter.

Ralph Pucci, the legendary mannequin manufacturer, designed his first mannequin in 1979. Pucci was bored with the stiff, motionless figures that populated store windows. A fitness craze had seized pop culture. The new Rocky film had just premiered. Jane Fonda was about to release her famous exercise videos. Barbara Paris Gifford, a curatorial assistant for The Art of the Mannequin, the forthcoming Ralph Pucci exhibition at the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, said Pucci wanted his new mannequin to reflect the visual tastes of the period. “It was modeled after a really athletic guy. They dressed it in very tight clothing,” she said. “People related to them in a very different way.”

In 1981, Ronald Reagan was voted in as president. A few years later, Arnold Schwarzenegger made his blockbuster debut as The Terminator. Stern jawlines, broad shoulders, and social conservatism were in again. The mannequins of this period lost their slim figures and smiling faces. In 1990, when People launched its inaugural 50 Most Beautiful People issue with Michelle Pfeiffer on the cover, one of Pucci’s mannequins was included among the beauties listed. The Olympic Gold—a strapping, energetic mannequin with a prominent basket who looked more like a Greek god than a department store model—was the work of American artist Lowell Nesbitt. “He is really buffed out. He’s a size 44 chest when mannequins were usually size 40,” says Gifford. “This particular mannequin was not supposed to wear clothes because it was just supposed to celebrate a beautiful male body.” Nesbitt designed him in homage to his friend and colleague Robert Mapplethorpe, the provocative photographer who died of AIDS in 1989. The Olympic Gold was not only a counteraction against right-wing repression but also a tribute to gay culture, which had suffered devastating losses in the wake of the AIDS crisis.

More than a decade later, in 2001, Pucci collaborated with artist Robert Clyde Anderson on a new set of mannequins. But this time, they were inspired by yuppies and the bourgeoisie who occupied New York City’s brownstones. Among them was Hamilton, a gray-haired, half-smiling mannequin whose body is characterized by soft lines. “He’s obviously older. He exudes some kind of success. But he’s not model-gorgeous in any way,” says Gifford. The confident, relaxed pose his body was set in suggested a certain type of sophistication and a particular kind of affluence. Hamilton wasn’t trying to sell us clothes. He was trying to sell us a lifestyle.

(Man)nequins Today

In 2010, designer mannequin manufacturer Rootstein introduced a male mannequin with an impossible 27-inch waist. While most people mocked the Rootstein mannequins, they revealed a modern shift in how society conceptualizes the male body. The fashionable male physique is thin and lean but not overtly muscular.

The storefronts of hip clothing brands—American Apparel, Uniqlo, and Urban Outfitters, among others—feature slim mannequins with subtle but never excessive muscle definition in the arms and chest, paragons of white hipster masculinity. Hipsters “seem simultaneously interested in incorporating the form but denying the substance of the masculinities they perform with their clothing, beards, and interests,” noted Tristan Bridges, an assistant professor of sociology at the State University of New York in Brockport, writing on the social science website The Society Pages. “For all their posturing, hipster masculinities appear (at least symbolically) intent on being taken tongue in cheek.”

But male mannequins haven’t just lost their macho figures. They’ve also lost their faces. Famed window dresser Simon Doonan popularized the use of conceptual, faceless, and sometimes headless mannequins during his career designing window displays for Barneys New York. These are the mannequins that can be seen staring blankly out of every retail clothing store window, high and low. They’re often rendered in a high-gloss white finish, and sometimes their heads are covered with wigs. Morrisette, who abhors the abstract turn, calls them “eggheads.” “You walk down any street, and you see egghead, egghead, egghead, high-gloss white, high-gloss white, high-gloss white, headless, headless, headless,” he says. “They’ve changed for the worse.”

These mannequins constitute a droll sameness in the landscape of shop window displays. But male mannequins, like men’s fashions, don’t exist to disrupt any binaries or subvert expectations. They largely exist to reproduce normative and homogenous conceptualizations of sex and gender; the mannequins in shop windows must be as inoffensive and unassuming as possible. This is why many of them are outfitted with “baskets” rather than anatomically correct genitals. Americans still harbor prudish attitudes toward genitalia, the penis in particular. So mannequins must be conduits for our physical ideals without challenging any of our cultural virtues. In 1995, when Stephen Sprouse was tasked with designing exhibits for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, he worked with Pucci to create mannequins for legendary rock stars like Axl Rose and Sid Vicious. While Sprouse argued successfully for mannequins that were anatomically correct, Pucci told Rolling Stone, with an industry-reflective primness: “We recommended against the genitals.”

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

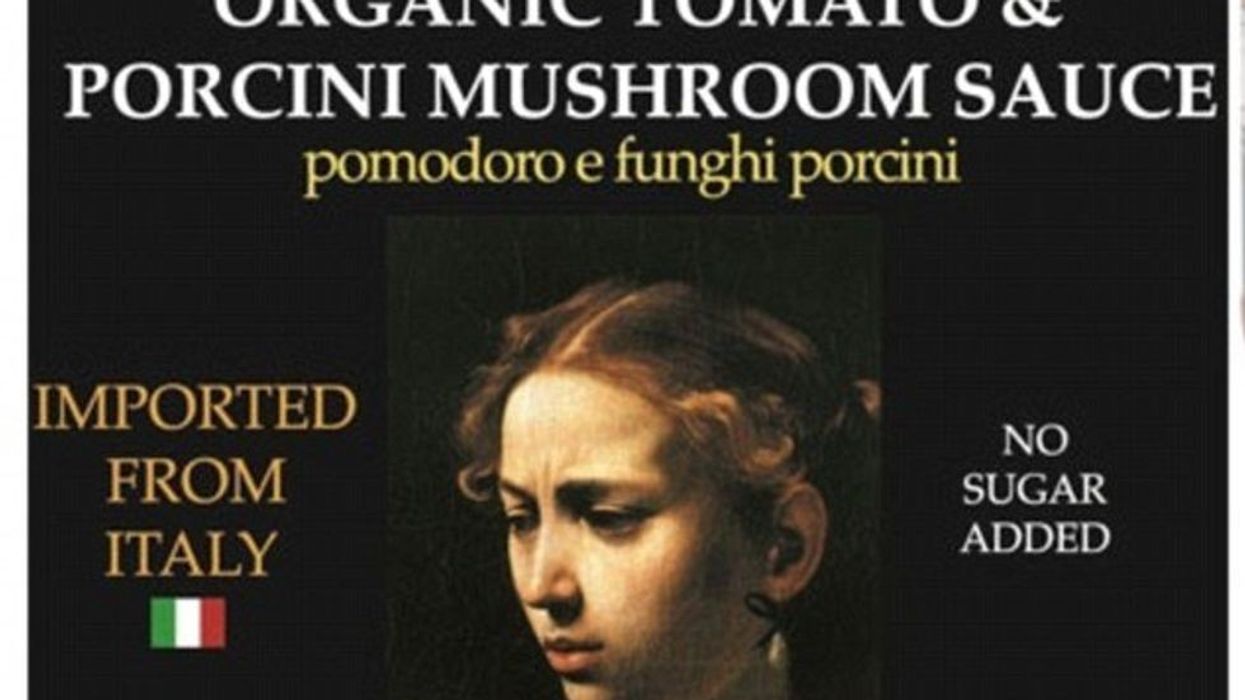

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)