The refugee crisis has never been abstract for award-winning poet Zeina Hashem Beck, who grew up in Tripoli, Lebanon—a nation where one out of every four people is displaced. People in exile are just part of her everyday experience, and thus frequently show up in her hauntingly political and deeply personal work. In her poem "Body," Hashem Beck writes of Hassan Rabeh, the young dancer displaced from Syria who killed himself by jumping from a seventh-floor balcony in Beirut last June. In “Naming Things,” she references the Palestinian pianist who played in the besieged Yarmouk camp until ISIS burned his piano and he fled to Germany.

Yet Hashem Beck is quick to point out that she doesn’t want her readers to think, “Oh, how sad.”

“Often you see a refugee on the news as a victim or a hero. We should feel sorry for them or hail the hero who’s sailed the seven seas! But the job of poetry here is to portray more complex stories,” she says.

Like all art, poetry has the power to speak across cultures. In Louder Than Hearts—her latest collection, released by Bauhan Publishing in April—Hashem Beck translates refugee experiences and displacement for a global audience. One doesn’t need to speak Arabic nor know her hometown of Tripoli intimately to feel her poems in an emotional and powerful way, whether she’s writing about war or resistance or taking on a more joyful topic, like Arabic songs, eating oranges, and dancing.

For World Refugee Day, I spoke with Hashem Beck from her current home in Dubai about why poetry matters in 2017, what it means to feel displaced, and why it’s the reader’s responsibility to research the towns, people, and historical events referenced in her poems.

You write a lot about current events. Do you see poetry as a form of reporting? Or is it more of an art?

I think all art is more than art, and art doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It always exists in a context. Most of the poems in Louder Than Hearts came into being from my immediate reaction to the news—my immediate, visceral reaction of anger or grief. Even if you’re not writing about refugees, I believe that you have to be engaged because it is the job of the artist to subvert and invert and question.

Do you think it’s important to humanize refugees through storytelling?

I want to comment a bit on the word “humanize” because I used to use it too. A friend of mine, who also writes about refugees, once said to me, “I don’t like the verb ‘humanize’ when it refers to refugees, because to humanize means to give human attributes to something that is not human and refugees are human beings.” So I’ve stopped saying it. We should think of these stories as stories.

About the importance of the storytelling: Humans tell stories so we don’t die, very simply. Why do we inherit stories from our families? It’s really almost a survival skill. Even cooking is a form of storytelling. I wanted to focus on that, on the details, in my poems. Even when there’s war, people continue to fight, make love, etc. I wanted to offer a more complex portrayal.

You write in English and not Arabic. Do you consider Arabic people to be your audience?

I don’t think that I ever had the choice, or maybe that's too extreme—but I wasn’t properly taught formal Arabic in the French school I went to. Although Arabic is my native language, and I speak the Lebanese dialect with my parents, the written is obviously different, right? I went to an English university, and Arabic, English, and French coexist within me at almost a cellular level. I belong to all of them and also to none of them. English just very simply came easier to me, but it’s my own English, influenced by Arabic and French.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]I do not write to feed the voyeuristic gaze of the Western world. I fight against it.[/quote]

As I’m writing a poem, I don’t think about who’s going to read it. The only reason I write a poem is because it feels absolutely necessary and inescapable for me to do so. I’m really happy when I see Arab readers come up, clapping and laughing. But I’m also happy when someone who’s non-Arab comes up. Still, I never ever want to hear someone say, ‘Zeina represents the Arab world.’ No. I do not write to feed the voyeuristic gaze of the Western world. I fight against it. I also don’t want someone to say, ‘Oh, those poor Arabs’ when they read my poetry. I want them to Google—just as I have Googled in my reading of ‘white literature’ ...despite the fact that that experience wasn’t mine, I built that bridge. That is what poetry does—it does build bridges. And I expect people to do the same. I’m giving the non-Arab reader some tools; I am not stranding them.

Do you see the political issues you explore in your work as ramping up since Trump’s election? If so, has that election given you a greater sense of urgency?

Of course, it was devastating to look at my phone and see that Trump was the president of the United States. I cursed! But I’m going to throw in a little bit of Arab humor here. When Trump was elected, I told my husband, ‘Well, America...welcome to the Arab world.’ Because as someone who’s lived in the Arab world since I was a little girl, I was exposed to the refugee crisis, even before Syria. I was always aware that there are refugees. I was always aware that there was war. I was always aware that there is racism, and sexism, and bigotry. Because there is racism in Lebanon. The Trump election didn’t exactly shock me. These were things I was already thinking about pre-Trump that now may intensify post-Trump.

And then there’s Trump’s travel ban, which had a big impact. Do you think that refugees are losing their safe havens?

We definitely are. People with green cards, with lives in America, were sent back with the Muslim ban. But you’re saying this with a U.S.-centric view. I am aware that there are people like Trump who support everything he stands for—which is, basically, me versus the other and the other is always evil. But I’m also aware there are people who don’t believe in that—there were people during the Muslim ban at the airports, carrying signs saying “Refugees welcome.” So I choose to believe in the goodness of people. Otherwise, I’ll just die of despair.

You were recently in America when the ban was still in place. How was that experience?

I was scared. I almost decided not to go, because, yes, Lebanon was not on the list, and yes, my experience doesn’t even compare to people with lives here who were sent back. I was just visiting, so the worst that could happen was that I would be questioned for hours and sent back to Dubai. But it was still a very stressful thing to go through. But I had friends within the U.S. saying: “Go, do it. Should anything happen to you, we’ve got lawyers, we’ve got you.” Once I was there, I was surrounded by individual safe havens—poets and writers. I did not feel unwanted.

You’re from Lebanon but have lived in so many other places; I’m sure you’ve felt displaced. Do you see a parallel in your own experience and that of the refugee?

For me to say that there are parallels means that I’m comparing my experience to that of a refugee. That would be appropriating the refugee’s pain and grief, which in no way compares to my feeling of displacement.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]I feel this pressure, a post-ISIS pressure, to justify the fact that I am not out to get you.[/quote]

I want to talk a little about the difference in the Arabic language between the words ghorbeh and luju'. Ghorbeh comes from ghareeb, “strange” or “stranger.” It means “estrangement.” And when you are living in the ghorbeh, as we speak here, as in my case, in a “strange place,” you’re not living in your home country. You’re away, you’ve probably been away and will be away for a long time. You are estranged, and you’ve probably done that by choice.

But the word luju' is totally different. It comes from the verb laja'a, which means to “take refuge”—as in “refugee.”

Do you ever feel, because of your religious beliefs, that you and your work are too often politicized?

I don’t mind you asking, but you know, I have to comment on this. I wonder if I would be asked that question if I was non-Arab.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]The poet is the anti-Trump, because the poet’s job is to care about the importance of words.[/quote]

That’s why I asked! I wonder if people are constantly making unfair judgments about you simply because you are Arabic.

I have to be completely honest here and say, I’ve lived for a long time in Dubai and Beirut, where it is the norm to be Muslim. I’ve never been the other. But you do feel the pressure, even in Lebanon, because sectarianism is still entrenched in society due to the civil war we had. Muslims and Christians killed each other.

So from time to time, you get the remark: “But you don’t look Muslim. You don’t act Muslim.” And you get the question, “What do you think of ISIS?” What do I think of ISIS? Seriously, why do I even have to say, “Oh I hate ISIS.” Of course I hate ISIS! That even happens in Lebanon, in my home country. Of course I have hope in a secular Lebanon, which I choose to believe also exists (I, myself, I’m married to a Christian). But yes, I feel this pressure, a post-ISIS pressure, to justify the fact that I am not out to get you. Even from some Arabs.

Speaking to how I identify, that's a very personal answer: I identify as a secular Muslim. I think people should just be reasonable. We’ve got scriptures—the Bible, the Quran. These texts do not exist in a vacuum. I’m all for interpreting and reinterpreting religious texts, and I am all against organized religion that brainwashes, against us versus you. My daily prayer, and I mean that, it’s not a metaphor. My daily prayer is poetry. I’m looking around me and questioning the world and connecting with it on a mental, spiritual, psychological level.

You pray daily. Do you write daily, as well?

I do not write every day, and I write in waves. When the poems aren’t coming, I just let them be. I let them stew. But the reading is daily.

What/who is giving you hope right now?

I think the people who always give me hope are the artists. I feel this sisterhood or brotherhood with the poets, the artists, the writers who are writing right now, reminding us that the world is still worth being loved.

So poetry still matters? Not everyone would agree.

The poet’s strength is in words. If you look at how Trump uses words—like the “covfefe” joke everyone is laughing about—I mean, it’s funny, really, and everyone does a typo, but I can’t help but see it as a symbol, that covfete word for the utter nonsense that he sometimes speaks. He has no care about what kind of impact his dangerous words can have, no care at all.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Will I write a poem today and free Syria tomorrow? No...But little by little, art brings about small changes.[/quote]

In that way, the poet is the anti-Trump, because the poet’s job is to care about the importance of words. Poetry is language at its most condensed. Poetry is not a luxury. It’s a necessity in every society, not just where you have a tyrant or a Trump or a war zone. Even in peaceful places, poetry disrupts and it revolutionizes. Even in peaceful times, it’s important. It takes care of our souls.

Whether or not poetry can bring about change is a question I constantly ask myself...and I think the answer is yes and no. Will I write a poem today and free Syria tomorrow? No. Will I write a poem today and free Palestine tomorrow? No. But little by little, I think, art in general and poetry in particular brings about small changes. Sometimes you read a poem that you feel has changed you on a microscopic level. I have to believe that or otherwise why am I doing what I’m doing? It builds small bridges.

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

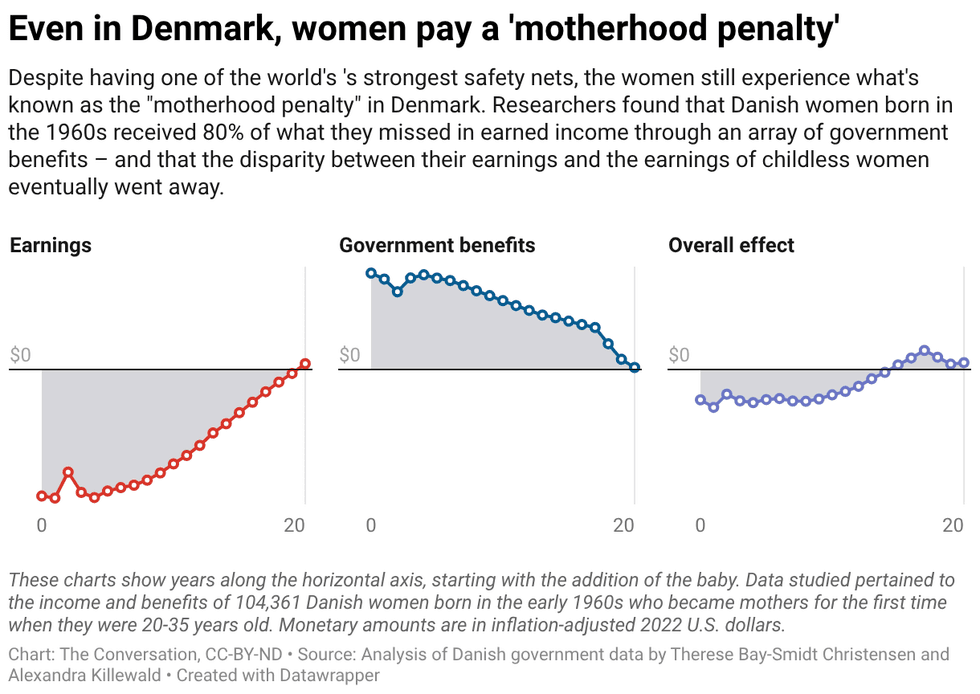

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit: