After an all-night drive up from Whitehorse, Canada, our small group of activists, artists, and outdoor enthusiasts begins the process of loading gear onto the floatplane dock at Mayo, a village of 200 inhabitants along the Stewart River in the heart of Canada’s Yukon Territory. Bleary-eyed, we load our supplies into two aircraft, then lash four canoes atop the planes’ floats. Five minutes after we are airborne, we swing around to the northeast and watch houses and roads and other signs of human life disappear beneath us.

For nearly two hours we climb over the wilderness, heading further north toward the high spine of the Mackenzie Mountains, which stretch nearly 500 miles from British Columbia to bisect the Yukon. We marvel at the green valleys and snow-dusted mountains below us. As clouds gather and then part, sunlight splinters into beams that bathe the sparkling, steaming summits with ethereal yellow light.

A full-throttle climb brings us over a final mountain pass with so little room to spare that it seems we could reach out and touch the spires on either side. We descend into Bonnet Plume Range, toward a pair of lakes near the headwaters of the Snake River. Once we land and unload and the sound of the departing planes fades into silence, we sit on pads of soft moss and take stock of our position. In the Lower 48, the most remote point—the southeast corner of Yellowstone National Park—is little more than 20 miles from a road. Here, just below the Arctic Circle, we are nearly 200 miles from the nearest highway.

With only 35,000 inhabitants, this California-size territory remains almost completely unsettled. Walled off by Canada’s highest peaks, the Yukon’s lake-dotted taiga, mountains, and river systems sweep down from the Beaufort Sea between Alaska to the west and the Northwest Territories to the east. Most of that land is drained by the Yukon River, which flows north and west nearly 2,000 miles across the Yukon and Alaska before emptying into the Bering Sea. But to the north of the Mackenzie range is the Peel Watershed, the largest constellation of wild rivers in North America. It is also home to bears, wolves, wolverines, sheep, moose, and vast herds of caribou in one of the few places left with an intact predator-prey ecosystem.

We spend 13 days on and around the Snake River, one of seven high-mountain rivers in the Peel Watershed. For more than a week we don’t see a single man-made object, or any sign that humans have ever been here. When we finally spot an empty, rusting oil drum atop a bar of bright red rocks just below Iron Creek, the effect is jarring.

A few miles up the creek, one of the world’s largest iron deposits lies buried beneath under a mountain. Discovered in 1961 and owned by Chevron, the Crest Deposit was deemed uncompetitive when there was little demand for steel in Asia. Now, it’s a different story. “Yes, it’s in a remote area,” says Claire Derome, of the Yukon Chamber of Mines in Whitehorse, the territorial capital. “But it’s not much more remote than some of the deposits being developed in Brazil or Bolivia, and we’re closer to Asia. With a rise in iron prices and a rail link to the coast, that could be a viable deposit.”

That kind of talk has the territory’s native leaders worried.

“These lands have sustained us in body and spirit for thousands of years,” says Simon Mervyn, an elder and former chief of the Na-Cho Nyak Dun First Nation, which is centered in Mayo. “The environment is not for sale,” adds William Josie, director of natural resources for the Yukon’s northernmost First Nation, the Vuntut Gwitchin, “A small mine needs a road, and one road leads to more roads.”

Derome’s remarks about bringing a wilderness resource to market sound distressingly familiar to embattled conservationists and indigenous peoples everywhere, and not just in the Yukon. Those groups struggle to protect wild places against relentless development, and as each year passes, they seem to be losing the fight. In Brazil, the government recently revised the Brazilian Forest Act, a globally pioneering piece of legislation that was first drafted in 1934. The revised act clears the way for hydropower plants on undisturbed Amazonian rivers and opens indigenous reserves to mining. In Malaysia, the World Wildlife Fund has spent years trying to convince the country’s government that it makes little sense to set aside a few beach sanctuaries for endangered sea turtles without banning the brisk sale of turtle eggs. Ten years ago, Chinese environmental activists won a rare victory, stalling construction of hydroelectric dams on the Nujiang River in the country’s biologically diverse southwest. Then, the government announced plans to build five megadams on the Nujiang and other waterways in the region. It’s not surprising that Jim Pojar, the former executive director of the Yukon Conservation Society (YCS), once wrote to his membership: “No doubt each of you, at some time, has been discouraged by the seemingly insurmountable social and environmental problems that confront us daily… No one, not even a relentlessly upbeat person like me, can escape an occasional bout of self-doubt.”

Unlike their counterparts in other regions of Canada, the 14 First Nations of the Yukon never signed any treaties with the federal or territorial government until the Umbrella Final Agreement, which was completed in 1993. In the agreement, native people gave up their land claims in exchange for a constitutional right to self-governance and participation in land-use planning. The agreement led to the establishment of the Peel Watershed Planning Commission to guide the region’s development.

[quote position="full" is_quote="false"]Those groups struggle to protect wild places against relentless development, and as each year passes, they seem to be losing the fight.[/quote]

After more than six years of study and consultation with stakeholders from every walk of Yukon life, the planning commission worked out a compromise that called for 80 percent of the Peel region to be protected as wilderness, with 20 percent open to development. The affected First Nations, which originally wanted the entire watershed deemed off-limits to development, accepted the plan and, in 2011, the Yukon government sent a letter to the commission in which it raised no specific objections to the 80/20 split. “Nobody got everything they asked for,” says David Loeks, who chaired the planning commission. “But we expected the agreement to be honored.”

Later the same year, elections further consolidated the power of the Yukon Party, which is heavily supported by mining interests. As more former mining executives filled the ranks of government, Loeks and others began to notice signs of “skullduggery.” Technical input from one government agency was censored, and the government gave permission to Dallas-based Hunt Oil to look for oil and gas in the watershed while the Peel plan was still under discussion. “Certain exploration and development activities can proceed,” John Spicer, of the Yukon’s Department of Energy, Mines, and Resources, said at the time. “We can’t stop the world and put it on hold.”

To conservationists, including Mike Dehn, who was then executive director of the Yukon chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS), it was clear that the territorial government had no intention of keeping the promises it had made. Karen Baltgailis, executive director of the YCS, remembers Dehn coming to a sober realization one day at the CPAWS office in Whitehorse: “Eventually we’re going to have to sue the bastards,” he told her.

On January 21, 2014, the Yukon government did what Dehn feared: Officials declared that they were unilaterally rejecting the Peel plan. Instead of protecting 80 percent of the area as wilderness, the government’s new plan set aside only 29 percent as protected lands. Furthermore, it allowed miners to build roads through those “protected” areas to access mineral claims elsewhere. Currie Dixon, a member of the Yukon Legislative Assembly who until recently served as Minister of Environment and Minister of Economic Development, told me, “The vast majority of my colleagues and I indicated we weren’t comfortable with the [watershed] plan. And since we won a majority government, we felt a mandate to proceed in a manner that was the correct one.”

The action stunned Aboriginal leaders and environmentalists, who spoke out on what they perceived as the government’s arrogance, betrayal, and lack of good faith.

“When the government did that,” says Gill Cracknell, Dehn’s successor CPAWS-Yukon, “it could have been a huge, depressing thing. But they had underestimated the level of commitment in the First Nations, and the degree to which public opinion among all Yukoners was going to shift against them.”

The growing interest in the issue surprised Roberta Joseph, Chief of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, whose tribal lands are in the vicinity of today’s Dawson City. “Usually native-rights issues don’t have strong public support. We have to support each other,” she says. “But with the Peel there were people you wouldn’t expect—miners even—who felt it was important that special places are taken care of in a good way.”

Cracknell notes another government blunder: “They also didn’t realize that we were geared up and ready to respond.”

Before the government’s decision, Dehn had called Thomas Berger, the most influential environmental and native rights lawyer in Canada. Berger had just won a Supreme Court of Canada decision on behalf of Manitoba’s Métis nation, a case that had stretched nearly 30 years. In his early eighties, Berger had vowed that the Métis case would be his last. “Well, you know I claim to be retired,” Berger recalls telling Dehn. “But that didn’t stop him. A few days later, Mike and Karen Baltgailis were in my office in Vancouver.”

Berger felt they had a strong case, and an important one, since it would set a legal precedent for how land claims are interpreted. Once Berger agreed to take on the case—“I thought, well, one more…”—the momentum picked up.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]They had underestimated the level of commitment in the First Nations, and the degree to which public opinion among all Yukoners was going to shift against them.[/quote]

“We had a big press conference in Vancouver,” Cracknell remembers, “and when we came back to Whitehorse we had the biggest rally ever held in the Yukon. The donations started pouring in, and everyone was saying, ‘We’d like to do a benefit concert, a zipline for the Peel, a 12-hour climbathon.’ That energy went right through to the hearing in July [of 2014].”

One sunny afternoon, we beach our canoes on the riverbank and hike to Mount MacDonald, a multi-spired wonderland of rock walls, glaciers, and hidden box canyons. We follow a milky white stream up the valley, springing over thick beds of sphagnum moss. Then we stop to rest in a hanging meadow. The ground is peppered with fireweed and arctic poppies and three kinds of berries.

As we share our lunches, I sit next to Scott Fleming, 43, a thoughtful, soft-spoken Ontario native. The former prospector would almost certainly have been a millionaire if he had continued hunting gold with his partner, Shawn Ryan, whose net worth has climbed to well over $100 million. Instead, Fleming decided to pursue a career in carpentry.

We look out over the jags of Mount MacDonald, where waterfalls tumble from small glaciers cupped between granite spires. It seems as good a time as any to ask Fleming why he quit on the eve of the big payoff.

“Shawn’s a great guy,” he says finally. “And he’s greener than most in the business. But being out on the land every day, seeing places like this, it had an effect on me.”

He meets my gaze. “I realized I didn’t want to be part of tearing it up.”

When Berger and the territorial government faced off in the Yukon Supreme Court in July 2014, it soon became apparent that every seat in Justice Ronald S. Veale’s Whitehorse courtroom would be filled. Officials rigged up a video feed to an adjacent courtroom, which soon filled up too. Conservationist Mike Dehn was not present—he had died in early 2013 from cancer.

Berger began his argument, speaking with the slow and eloquent dignity of an elder statesman, laying out his argument, explaining each party’s obligations under the agreement. He pointed out that the Yukon First Nations had given up their claims to an area the size of Spain in exchange for the right to have a say in how their traditional lands would be managed. The government, Berger continued, was constitutionally obligated to honor its treaties, as well as the assessment processes that flowed from those treaties.

A few months after Justice Veale heard final arguments, Baltgailis found herself in downtown Whitehorse on a dark December morning. Retired from the YCS, she decided to stop by her old office to say hello. “I had no idea that I was about to open the door on the culmination of 20 years of work in the environmental movement,” she says.

A few minutes earlier, her successor, Christina Macdonald, had received an email from the Supreme Court. She excitedly called her staff and volunteers into her small office to read what looked like a decision in their case. “There were five of us crowded around the computer, frantically scrolling through the document, trying to find a bottom line in the legalese,” Macdonald says.

Then another email arrived in her inbox. This one was from Berger. He’d written just two words, instantly understandable to everyone except mining coordinator Lewis Rifkind, a Scotsman who had come to Canada via South Africa.

“Christina,” Rifkind asked, “What does ‘home run’ mean?”

Baltgailis opened the door to a chaotic, ecstatic scene. “People were jumping up and down and hollering,” she says. “I was enveloped in hugs.”

Macdonald waved her into her office to show her the decision, which stated that the government did not have the authority to override the plan to preserve the bulk of the Peel region. Veale also scolded the Yukon government for breaking its deal with the four First Nations whose traditional territories are within the region. He wrote that the government’s actions ran counter to the goal of reconciliation with First Nations and were “inconsistent with the honour and integrity of the Crown.”

Three hundred miles to the north, Chief Roberta Joseph was in her office at the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s headquarters when the email came in. “It was almost a surreal experience,” Joseph says. “I was excited and anxious, and the court document seemed to be saying that the government erred. Then Tom’s note came in, and I jumped up and let out a little ‘Yahoo!’ and ran out to tell everyone.”

In Whitehorse, Baltgailis bought champagne while Macdonald put the news up on Twitter and Facebook. As word spread, more supporters arrived, and impromptu parties broke out at YCS, CPAWS, and the headquarters of each First Nation. “I ran through town when I heard it,” Na-Cho Nyak Dun elder Jimmy Johnny says. “I told everyone that the judge said the government did something they shouldn’t have done. That made me really, really happy—to the point that I cried that day.”

The ruling quoted extensively from Loek’s introduction to his commission’s plan. “On a personal and professional level, that victory was a vindication,” Loeks says. “I can’t describe the exhilaration and exaltation. So often we end up disappointed in life. But here, finally, was something so important and so necessary and so good coming down.”

That afternoon, Baltgailis and Macdonald went for a walk, stepping into the streets of Whitehorse to find an elated atmosphere. “But there was also a part of me that kept expecting someone to jump out and say, ‘Surprise! Just kidding!’ That lasted for about a week, until we had a big victory party that people came to from all over the territory.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]I can’t describe the exhilaration and exaltation. So often we end up disappointed in life. But here, finally, was something so important and so necessary and so good coming down.[/quote]

Though the territorial government may follow through on its threat to appeal the decision, Veale’s ruling was decisive, and “legally bulletproof in terms of its reasoning,” resource analyst Bill Gallagher told CBC Radio. “This is a huge win that has application nationally.” Loeks adds, “The remaining open spaces in the North have a fighting chance.”

“It’s a great victory for the First Nations, the environmental organizations, and all Yukoners,” Ed Champion, former Na-Cho Nyak Dun chief, says. “In the end, one of the world’s last great wilderness areas will be protected.”

Winter weather.

Winter weather.

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from  A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

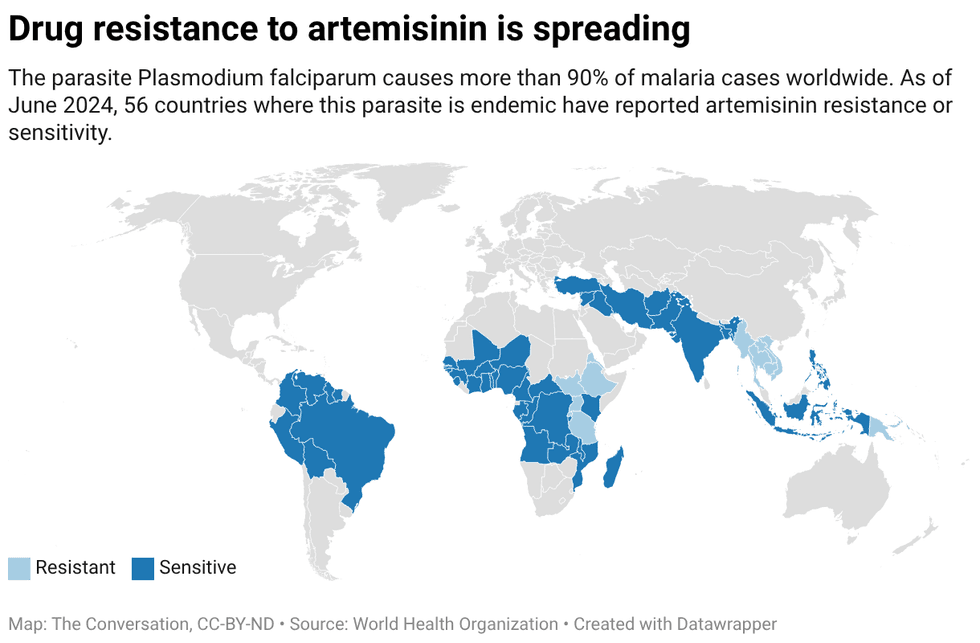

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Created with

Created with  Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,

Where to turn off autoplay in your account on Facebook’s website.Screen capture by The Conversation,