In the midst of the Ebola’s arrival in the United States one thing is clear: the American public is vulnerable to hysteria and panic without the unifying voice of a trusted health leader—a surgeon general, for instance.

In just a few short weeks, fear of the deadly epidemic has gripped America, aided by the spread of misinformation in the mass media. The latest case of Ebola in the United States was announced last week, when a doctor returning from Guinea, where he was working to help treat the disease, arrived home in New York and was admitted to Bellevue Hospital with a high fever. The case has already caused panic in the city, where health workers are trying to retrace the man’s steps the day before he was hospitalized.

While various medical experts have tried to counter panic-button pushers with details of how the virus really spreads and the true, small threat to most Americans, a surgeon general–the president’s choice to serve as “America’s doctor” on matters of public health–might be the single, powerful voice of reason needed to calm a nation.

The Office of the Surgeon General doesn’t set policy, but it does oversee the Commissioned Corps of the U.S. Service of Public Health—a 6,500 member group of highly trained public health experts, including doctors, nurses, dentists, etc., who are ready to assist in health emergencies here and around the world. Previously the surgeon general has dispatched this corps to disaster areas, like states affected by Hurricane Katrina. Recently, a small group was sent to Liberia to help care for Ebola patient health workers.

But, given Americans’ current lack of confidence in government, would it be worth the effort to muscle through the stalled confirmation process?

Those in the public health field say yes. “There is no question we could use a surgeon general right now who is above the fray and providing leadership and reassurance,” says Dr. Arthur L. Reingold, professor and head of epidemiology at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health.

Staying above the fray, remaining an independent spokesperson for public health, is what makes a surgeon general so effective.

But that’s not easy to do, particularly in today’s political climate.

The quintessential surgeon general

Over the past three decades, the surgeon general’s authority, as well as respect for the office, has swung wildly.

The nation’s most famous surgeon general was C. Everett Koop, M.D., a Brooklyn-born pediatric surgeon appointed by President Reagan in 1981. “He had a gravitas that was grandfatherly and reassuring,” Reingold said. “He had long experience as a real doctor that people found comfort in.”

Koop’s two primary efforts were to get Americans to stop smoking and to promote HIV/AIDS education, and the forceful doctor wasn’t afraid to ruffle feathers on the left or the right of the political or social spectrum. “He turned out to have extraordinary decency and willingness to put health above politics, particularly in regard to HIV/AIDS, despite his own views, which were conservative,” Reingold said. For instance, Dr. Albert Wu, professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said that Koop “advocated for the use of condoms and was an advocate for early AIDS education.” He mailed a brief version of his office’s report on AIDS to every household in America and insisted that AIDS patients not be stigmatized.

His anti-smoking stance also led to smoking bans in public places. The New York Times obituary for Koop (who passed away in February, 2013) noted that when he became surgeon general, 33 percent of Americans smoked, and when he left that office in 1989, that number had dropped to 26 percent.

He was following in the footsteps of an earlier surgeon general, Dr. Luther Terry, who took the courageous stance in 1964 to publicize the newly discovered connection between lung cancer and smoking. This led to warning health labels on cigarette packages.

But things had changed five years after Koop’s departure. Dr. Jocelyn Elders, appointed surgeon general by President Clinton in 1993, was also outspoken about the value of sex education in schools, including frank encouragement of masturbation and contraception, and was a skeptic of the War on Drugs. After just 15 months she was forced to resign because of her comments. Her eventual successor, Vice Admiral David Satcher, again focused on a sex education policy that was criticized by conservative groups as being too permissive.

Some surgeon generals have chosen to stay clear of contentious issues. Dr. Regina Benjamin, surgeon general from 2009 to 2013, emphasized the benefits of exercise and breastfeeding. Dr. Richard Carmona, surgeon general during George W. Bush’s presidency, made more waves after leaving office rather than during, when he denounced the administration for allowing ideology to trump scientific findings in regards to embryonic stem cell research, sex education and secondhand smoke. He later testified that he was pressured to toe the administration line on these topics and others.

The challenges of a health leader

Dr. Vivek Murthy, the current surgeon general nominee, incurred the wrath of the NRA and its supporters by recommending gun control measures after the Sandy Hook school shooting. At 36, he is also thought by some to be too young—though unlike some Republican politicians claim, he has plenty of medical credentials. As a result, his nomination has been stalled in the Senate for nearly a year, leaving the job to acting surgeon general, Rear Admiral Boris D. Lushniak.

Looking for an expert response to the spread of Ebola, the media turned to Dr. Tom Frieden of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. President Obama then appointed an Ebola “czar,” former White House advisor Ron Klain.

But neither seems to possess a surgeon general-like reassurance.

“On one hand, we have a new czar who is not a disease expert—he was put there to administrate, to pull all the pieces together so things happen smoother and faster,” said Dr. David Eisenman, associate professor of Medicine and Public Health and Director, UCLA Center for Public Health and Disasters.

“On the other hand, we have Thomas Frieden, the head of the CDC—who is a very well respected public health expert but whose credibility was damaged with some missteps.”

Early on, Frieden asserted that Ebola would be stopped in its tracks (though the CDC head probably meant that this was his intention, not fact, says Eisenman). Later, the CDC team allowed an infected nurse to fly on a commercial jet, another mistake. Although the CDC made rapid adjustments to its procedures, public confidence in the agency has taken a nosedive. A recent CBS poll of 1,007 Americans showed that just 37 percent of respondents said they thought the CDC was doing an excellent or good job—down from 60 percent recorded in a May 2013 Gallup poll.

The closest thing to surgeon general-like authority has come from Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health, who has made numerous media appearances, most recently to argue against New Jersey and New York’s mandatory quarantines for healthcare workers returning from West Africa. Yet his voice is still drowned out by TV and radio personalities (who have no medical background) providing uninformed opinions about how America should respond to Ebola.

“A surgeon general might at least help to balance the cacophony of panicked messages coming from every other corner,” Wu said.

Planning for the Ebola of the future

After the Ebola health crisis improves—“And it is already improving in the United States,” says Eisenman—a clear-eyed assessment of America’s preparedness, led by the surgeon general, would be key.

“We’ve lost a lot of money for crisis preparedness,” Eisenman said. “We see the human toll this can take. The surgeon general could keep us focused, so that we remember to prepare for a crisis when things are good.”

A surgeon general might also be able to advocate for a vaccine. Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, has suggested that were it not for budget cuts in medical research over the last 10 years, a vaccine for Ebola might have already been developed. Others have said that big pharmaceutical companies were not focused on a vaccine because the virus was not in this country.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]There is no question we could use a surgeon general right now who is above the fray and providing leadership and reassurance.[/quote]

A surgeon general could also take this opportunity to remind us that there is one virus that hits America hard every year: the flu.

“The crisis that is guaranteed to kill millions people this year is influenza,” Wu said. “In a bad year, there are 100 million cases of flu worldwide and vaccinations in the U.S. could go a long way. A surgeon general now would really emphasize the importance of being vaccinated against measles, whooping cough, and flu—all of which are on the rise.”

With Murthy’s confirmation as the next surgeon general up in the air, the question must be asked: Could anyone do this job—from flu vaccination advocacy to stemming a pandemic panic—effectively in the America’s political climate?

“Many people who would be good candidates would be considered ineligible because of the current political environment,” Reingold said. “You’d have to find someone who could wiggle through the narrow political corridor to be appointed—someone who has the credentials and is willing to take this on.”

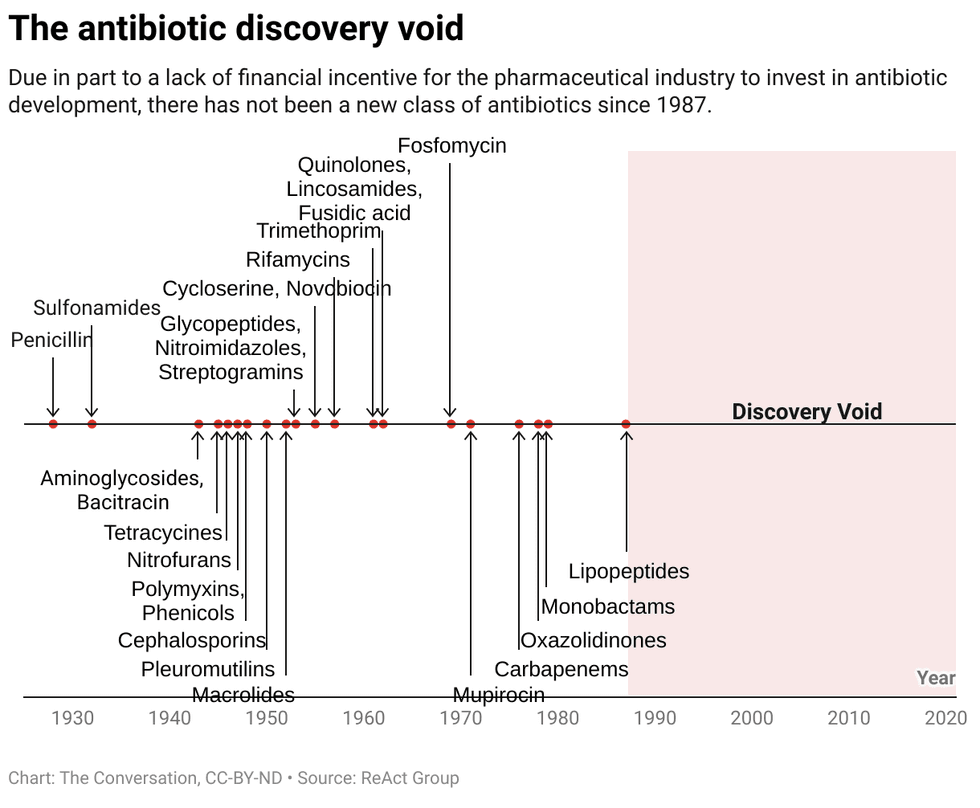

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

An envelope filled with cashCanva

An envelope filled with cashCanva Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Two penguins play by the waterCanva

Two penguins play by the waterCanva

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit  Oil production.Photo credit

Oil production.Photo credit  Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit

Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

A flight attendant closes the overhead binCanva

A flight attendant closes the overhead binCanva Gif of Larry David trying to put his luggage in overhead compartment via

Gif of Larry David trying to put his luggage in overhead compartment via

Dog owner pets their dogCanva

Dog owner pets their dogCanva Gif of a sad looking pug via

Gif of a sad looking pug via