We’ve all felt it: that ice cream that’s just a little too cold, that popcorn that gets a little too stuck, that coffee that’s a little too hot. But how did such sensitivity in our teeth develop? Researchers at the University of Chicago have begun to develop an answer, and it’s not what you’d expect.

What they found was that ancient fish were covered in small, bumpy structures that helped them traverse the ocean and avoid predators. These are called odontodes, which functioned almost like armor, and these structures contained miniscule tubes of dentine. In humans, dentine is the layer under the enamel of our teeth. Dentine is very sensitive because it ensures the safety of the tooth’s internal nerves, tissues, and blood vessels, also known as dental pulp. According to Cleveland Clinic, “the nerves in your dental pulp detect changes in temperature and pressure. The resulting discomfort lets you know something is wrong.” The same, it turns out, was true for fish some 465 million years ago, though their odontodes were exterior features. Through the beauty of evolution, we developed similar attributes, albeit in our mouths instead of on our skin.

Below:

Paleontologist and postdoctoral researcher Dr. Yara Haridy joined the University of Chicago's research team in 2022 to "study the oldest skeletons of 'your inner fish'" and "dig into deep time to find out why our bones and teeth do what they do," she wrote on Instagram.

While odontodes were discovered many years ago, CNN reports, their purpose remained a bit of a mystery. It wasn’t until the UChicago team discovered that they contained dentine that they were able to surmise how the odontodes were used. “'Covered in these sensitive tissues, maybe when [a fish] bumped against something it could sense that pressure, or maybe it could sense when the water got too cold and it needed to swim elsewhere,’” Dr. Yara Haridy told CNN. “‘This shows us that ‘teeth’ can also be sensory even when they’re not in the mouth.’”

As these fish evolved, odontodes moved closer and closer to the mouth, until eventually they were inside. This is what’s known as an exaptation, as opposed to an adaptation. An exaptation is when “evolution has made do by co-opting an existing trait for a new use when the right circumstances arose,” according to Quanta Magazine. “These instances offer the lesson that a trait’s current use does not always explain its origin.” An adaptation, on the other hand, “tunes a trait or system over time,” according to the Journal of Molecular Evolution. That we have dentine in our own teeth isn’t magic, especially since our limbs were initially developed for swimming (another exaptation).

"Here are images produced by paleontological artist Brian Engh to show an "updated reconstruction of the currently oldest known bony fish - called Astraspis - evading a giant predatory sea scorpion called Megalograptus," he wrote on Instagram. "Each is meant to be sensing the other thanks to their sensory-bump studded armor body covering. In other words, what we were trying to show here is the FEEELING of being one of our most ancient bony ancestors trying to dodge an equally sensitive armored predator." Engh shows his art process below.

There are still fish that have odontodes today, too, and some have become even smaller, known as denticles, according to CNN Haridy knew the suckermouth catfish she raises had denticles but she also “realized their denticles were connected to nerves much in the same way that teeth are in animals,” the network added.

Based on their research, the UChicago team has noticed that early arthropods developed comparable qualities, albeit independently of one another, in a phenomenon known as “evolutionary convergence,” also called “convergent evolution.” According to London’s Natural History Museum, “Convergent evolution occurs when organisms that aren’t closely related evolve similar features or behaviours, often as solutions to the same problems.” This means that different species can develop the same attributes even if they haven’t arisen from the same source. Arthropods needed to stay safe too, after all, though their versions of odontodes are known as sensilla, CNN shares.

So, the next time you have some tooth pain, don’t worry–it could just be an aftereffect nearly 500 million years in the making.

A woman looks at post-it notes while thinking Canva

A woman looks at post-it notes while thinking Canva Two women on a couch are having a conversationCanva

Two women on a couch are having a conversationCanva A father and son sit on a porch talking Canva

A father and son sit on a porch talking Canva A woman paints on a canvasCanva

A woman paints on a canvasCanva A student high-fives with his teacherCanva

A student high-fives with his teacherCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva Waves crash against rocksCanva

Waves crash against rocksCanva

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:  An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:

An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:  Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:

Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:  Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

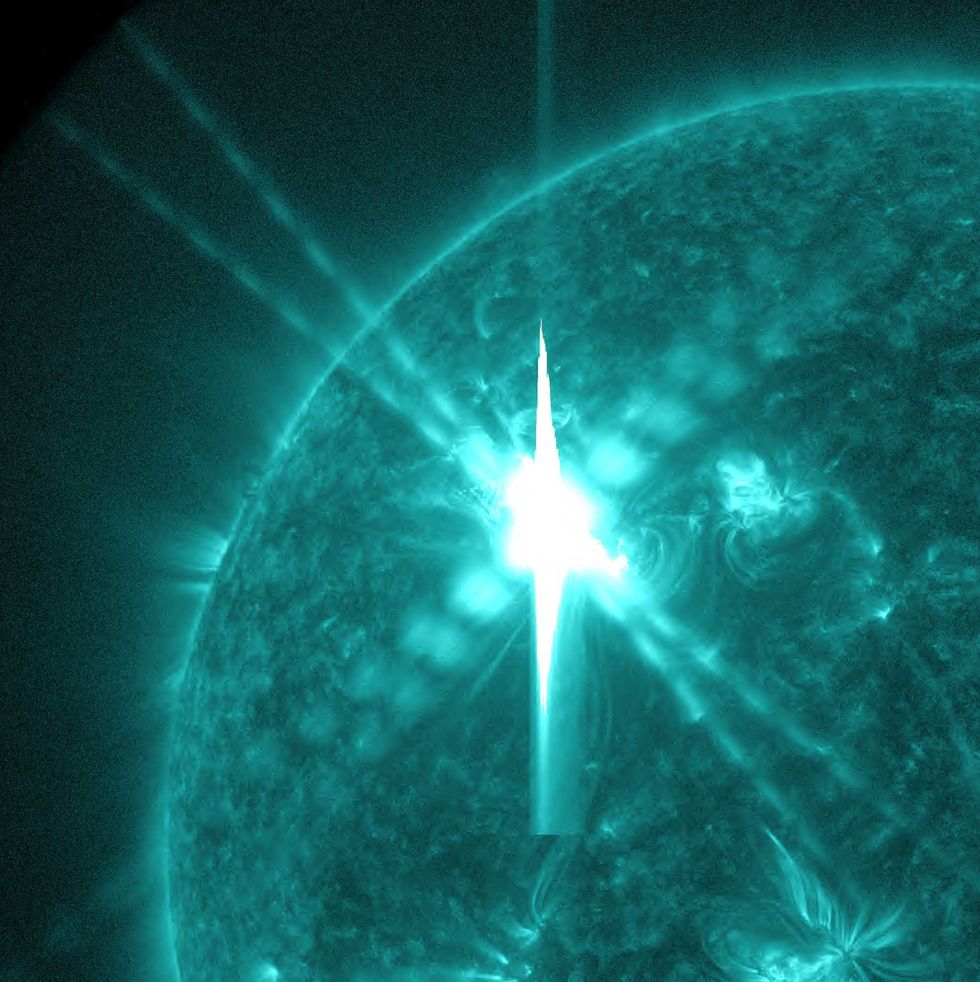

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Brady Feigl in February 2019.

Brady Feigl in February 2019.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.