Tiny houses.

We all love them, with their wee-size frames fit for a forest gnome and their Instagram-worthy décor that makes us want to throw away all our belongings—except for one decorative pillow, three books by Jack Kerouac, and forty-five potted succulents.

We also love them for their supposed cost effectiveness. Many of us daydream about the simple and inexpensive lifestyle these houses can offer: no more rent or mortgage payments; no more debt; no more living paycheck to paycheck.

These days, Americans are spending up to half their income on their homes—the average price of which is $309,200 (though don’t forget to include interest, taxes, and repairs). It can take decades for a family to pay off the loans for the roof above their head, or even in some cases, their $146,000 mobile home. The tiny house movement definitely has its allure—but are micro homes truly as cheap as they are chalked up to be?

As someone who has been intrigued by tiny houses for a long time, I’m curious—especially because I’ve seen more and more “tiny homes” listed at $500,000, like this bungalow in Brooklyn or this minimansion in Maryland. So, I went in search of tiny house minimalists across the country to get the real scoop on what it’s like to live small.

Materials: $15,000 to $30,000

The average cost of a tiny house is roughly $23,000. But to keep this number low, owners typically have to maintain a square footage of 186 square feet—which is smaller than most people’s master bedrooms—and build their own home with mostly salvaged materials, such as reclaimed windows or flooring.

Each home begins with the frame, which, depending on whether you want to be stationary or mobile, can be a foundation or wheels—both cost around the same ($10,000-$15,000). The standards of every tiny home include: doors ($500-$1000/each), windows ($100-$500 each), flooring and shelving ($5-$10 per square foot), and cabinets ($100-$650 per linear foot). After adding up the framework, tools ($1,000), plumbing ($2,000), electrical ($500) appliances ($1,000-$4,000) and other odds and ends, the costs for the most basic home typically range from $15,000 to $25,000—which is a higher cost per square foot than a conventional house, but cheaper overall. A 186-square foot house built for $25,000 will cost $134 per square foot, while the average 2600-square foot house built for $300,000 will run you $115 per square foot.

Filmmaker and tiny house dweller Christopher Carson Smith anticipated spending $15,000 on his 124-square foot home in Boulder, Colorado, but ended up dishing out $26,000. He admits that he probably could’ve spent even less by finding more used materials, but when you’re building your home with your bare hands, time and energy becomes a valued commodity. “You can get a free hardwood floor if you’re willing to remove it from somewhere else,” Smith says, recommending Craigslist, PlanetReuse, or nearby demolition sites.

In order to stay around his $25,000 budget, Alek Lisefski, who works at a consulting group for tiny house rookies, had to build the 160-square-foot home himself—while working a full-time job. “It’s a big commitment to take on a project like this, Lisefski says. “It was challenging physically and emotionally. I was working nearly full-time while building, and taking every evening and full weekends to build. It was an exhausting routine.” Alek ended up spending roughly $30,000, which included the cost of the trailer ($3,500), windows and doors ($5,500), roofing and siding ($4,000) and “all the nice stainless appliances” he wanted for his “dream house” ($3,500).

If building your own home sounds like too cumbersome of a task, you have two options: buy a completed home or contract a builder to customize your home for you. A basic completed home from the most popular builder in the industry, Tumbleweed Tiny House Company, will run you about $62,000, while a contractor will average at about $35,000. There are many pros to doing both—mostly not losing a lot of time and energy doing it yourself, but Lifeski recommends doing your research carefully before buying. “Make sure you find former customers and personally check with [them] to make sure they are happy with the house they received.”

Parking: free to $30,120

Time and energy aren’t the only hidden costs of owning a tiny house—so is parking.

Many tiny-home-owners choose to rent lots in different tiny house co-ops and communities around the country, where monthly prices range from $250 to $500. If you’d rather buy a lot in these communities, it could cost as much as $65,000.

Portland, Oregon-based tiny house resident and builder Lina Menard used to spend $250 a month on parking for her 100-square-foot home at the tiny house co-op Simply Home Community. That plus $50 in utilities and a $25,000 withdrawal from her IRA to pay for the build meant that her tiny house didn’t initially compete with the “quirky and awesome” below-market places she was renting. But cost wasn’t what was most important to her. “There were, of course, dozens of other nonfinancial benefits,” she told me, “like living in a sculpture I made myself, knowing I’d always have a roof over my head, having a house that perfectly suited my needs, having my own four wall and knowing I wasn’t throwing my money away on rent.”

Some owners have found people outside of the tiny house community who are generous enough to allow them to park for free or for a small fee on their property. Lisefski, for example, is willing to pay rent to park his home, but he’s also interested in bartering through yard work, pet/child care, or web design. Other owners, such as Laura LaVoie, who lives in a 120-square foot home she and her partner built in North Carolina, already owned land; they bought their property for $100,000 in 2007 before the economy collapsed.

Depending on where you live, you can spend anywhere from $1,500 to $196,000 per acre. The top five tiny house friendly states are California, Texas, Florida, Oregon, and North Carolina. If you choose to buy a 5,000-7,000 square foot lot in the popular East Austin area, the price tag will be between $200,000-$300,000; however, if you want five or more acres near in western North Carolina, you’re likely to pay well under $100,000 total.

If you build your house to be portable, you’ll need a truck to pull the home to your new location ($500-$30,000 if you rent or buy a used one) and insurance for towing. Lisefski was able to get a commercial trucking policy for around $120 when he relocated his home from Iowa to California.

Permits and policies: $1,725

Other costs to consider depend on whether you have a tiny house on a foundation or on wheels. If you are planning on staying put, your house will most likely be considered an accessory dwelling unit, which means you must apply for permits, which can range from hundreds to thousands of dollars depending on where you live. In Austin, the permit fees would total around $1225, which includes plan review, tree review, building permit, electrical permit, mechanical permit and plumbing permit. And don’t forgot house insurance, which typically costs around $500 a year.

Off-the-grid fixtures or utilities: $2,000-$12,000

The appeal of tiny houses is the ability to be kinder to Mother Earth by not relying on city services. Solar panels, compost toilets, and rain barrels are all common appliances found in the off-the-grid faction of the movement. A typical solar panel kit costs around $10,000, though depending on the size of your home and how much energy you use, you can find kits for as little as $500. If you don’t mind handling your own stank, you can get a super easy-to-install compost toilet on Amazon for $1,000, and you can supply all your water needs with a rain barrel ($500-$1000). Of course, all of these energy-efficient fixtures will have a quick return on investment.

If you choose not to go green, you’ll probably end up using city services such as electricity, water, gas, and sewer. Because a tiny house typically uses less energy, chances are your utilities will be lower than the average citizen. Numbeo, a user contributed database for cities, says that the average cost for utilities for a 915-square-foot apartment in Austin, Texas, is an $157. Cut the apartment size by three-fourths, and you’re looking at utilities at around $39 per month. If you decide to hook up at an recreational vehicle park, the utilities are often included in the monthly rental of $500-$900.

Time is money: $25,000-$75,000

Most tiny house builders will tell you that despite the challenges of building their own house to save money, the experience was 100 percent worth the challenges. “The best thing I got out of the tiny house process,” Smith says, “was the process of building. What I learned and how I grew was in itself and education. You’re getting that, plus a house that you can sell, keep forever, or have as an asset.” Most people I talked to still have their tiny homes, even if they don’t live in them anymore.

“If you want the empowering experience of learning to do it all yourself, by all means do that,” Menard adds. “But know that you’re also going to be paying for your education.” In case you’re wondering how much that education is going to run you, here’s a breakdown. Say you work on your tiny house for one year and act as general contractor, handyman, carpenter and plumber. All in all, you spend 1000+ hours secreting blood, sweat, and tears on your dwelling. The aforementioned roles cost up to $75 an hour, which means your time is worth $75,000.

Total (if you go the DIY route): your blood, sweat, and tears plus $20,000 to $30,000

Total (if you hire a pro or buy prefab home): $50,000 to $449,000

It turns out that a micro home can be extremely economical, both in the short term and the long term—that is, if you go the most basic route. It is relatively easy to keep your initial house cost under $30,000, but that also means devoting a year to building your home. If you’re lazy, like me, and employ a contractor or buy a prebuilt tiny home, you could be looking at six-figure prices, depending on how luxurious your tastes are. Then, of course, you have to factor in where you want to live and whether you can rent or buy. In the long run, if you maintain the minimalist attitude that comes from joining the tiny house movement, it’s worth it. Because they are so small, the expenses will still be cheaper than the standard American home.

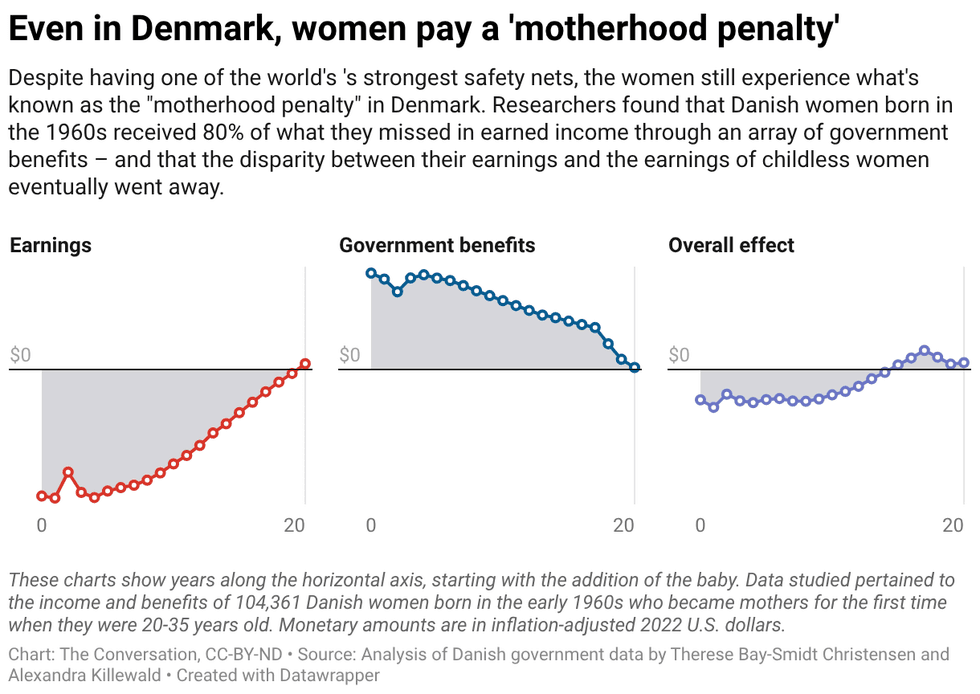

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents. Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.