With a President-elect who regularly blows off steam via ill-advised 3 a.m. tweetstorms, self-control may appear to be in short supply these days. But the ability to delay gratification remains an important skill. Every time you walk away from an argument that you know will lead to a fight, or put away your credit card because you won’t have the money to pay it off for quite some time, you’re resisting immediate rewards in exchange for potentially bigger future rewards. And it turns out that people with stronger self-control are better able to empathize with others—including their future selves—according to new research published in Science Advances.

European researchers at the University of Zurich and the University of Düsseldorf who study self-control and impulse control, investigated a brain region called the temporoparietal juncture (TPJ) that becomes active when taking the perspective of another person. In short, the TPJ is the area of the brain dedicated to selflessness. The larger the region, the more generous you’re likely to be, while electric stimulation there has been shown to lead to more empathy. The Zurich-Düsseldorf team was surprised to find that the same brain region lights up when one exhibits self-control of any kind, leading to an unusual conclusion that, “The future self is kind of like another person,” says Alexander Soutschek, lead author of the study and professor of economics at the University of Zurich.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Those who have better self-control abilities are happier in later life, less overweight, and perform better in their jobs.[/quote]

In other words, when you exhibit self-control, you’re essentially relating to your future self the way you would another person—and thinking more on that future self’s behalf than that of your present self. Being able to take on another’s perspective is associated with stronger social behavior, Soutschek says, adding, “Those who have better self-control abilities are happier in later life, less overweight, and perform better in their jobs.”

To see if their findings held up, researchers administered two rounds of “classical self-control tasks to link perspective-taking with the ability to exert self-control,” he says. Mirroring the famous marshmallow test—in which children were seated before a tasty treat and asked to resist eating it so that they could receive a later reward of two marshmallows—these subjects could “choose between 80 francs today, or 160 francs in one month,” Soutschek says of the first task. The subjects really did receive the money after the test. Next, they also had to choose between a payoff they would personally benefit from, or a payoff in which they benefited slightly less in order for another person to benefit.

The team then disrupted the TPJ region using non-invasive transcranial stimulation. Rather than boosting empathy, people tended to act more impulsively (choosing the immediate payoff), as well as acting more selfishly (choosing more money for themselves over sharing the benefits with others). Messing with the brain’s empathy center turns you into a jerk—to your future self and others.

Psychoanalyst Scott Von, Ph.D, director of the New Clinic in New York City, believes this research is particularly relevant, given America’s particular political climate. “We are no longer in the ‘culture of narcissism’ that the baby boomers talked about, but what I call a ‘culture of egoism,’ where we care even more about our status and reputation than our selfish pleasures or self-control,” he says. American society right now “may reflect a set of false selves and pretense to civility—while hate, fear, resentment, and selfish manipulation lie under the surface,” which Von sees as “more evident during the recent election and surrounding events.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]It’s well-known that addiction patients are suffering self-control deficits.[/quote]

While the self-control research will have many implications, one of the most potentially important will involve how we treat addiction, says Soutschek. “It’s well-known that addiction patients are suffering self-control deficits,” he says. While the focus in the treatment of addiction has primarily been on impulse control, “our idea is if there’s a second self-control mechanism in the TPJ, then self-control deficits may (also stem) from deficits in perspective-taking.” He envisions new approaches to addiction treatment, such as cognitive training “that could direct attention to the future consequences of your behavior,” and stimulation of the TPJ.

So the next time you find yourself baited for a fight, tempted to slap down cash you don’t have, or about to indulge in a calorie-laden snack you really shouldn’t, practice holding back. Even if delaying gratification doesn’t come naturally to you, you’ll benefit from an arguably less delicious, but much more valuable reward—in the form of physical, mental, and social health.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

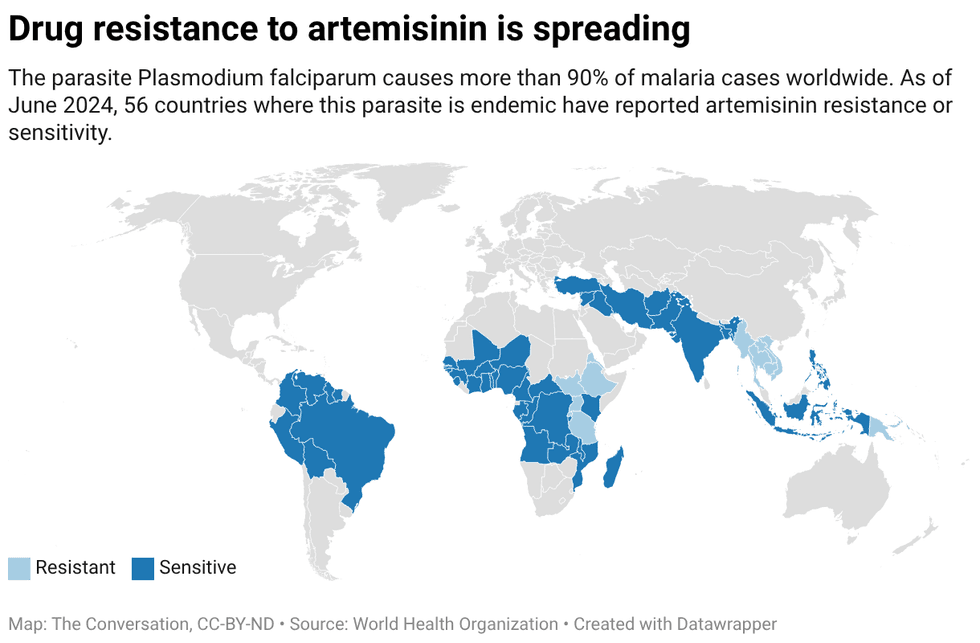

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.