America's medical system is so unnecessarily complex and confusing that you can get a master's degree in medical billing. One of the major problems with this Frankenstein's monster of a system is that patients often have no idea what they're paying for services.

You'd think that one of the advantages to having a private healthcare system would be the ability to make decisions based on price, as we do with everything else. But it never really seems to work that way.

In fact, about one in five visits to an in-network emergency room results in a "surprise" out-of-network bill that can drive up the cost by thousands. These bills happen when an out-of-network provider is unexpectedly involved in a patient's care.

(It's unexpected for the patient, but as you'll see, not for the hospital in many cases.)

These out-of-network doctors then ask for large fees that aren't covered by insurance.

This happened to me about ten years ago when I went into surgery to have a procedure on my foot. I was told the cost would be around $1200 after insurance. But a few weeks later, I got a bill for $2200. Evidently, the anesthesiologist was out of network.

Funny thing is that no one told me that at the time. Wouldn't it have been fair for someone to let me know the bill was about to double? As a patient, shouldn't I have the right to refuse service if it's going to cost me $1,000 more than I was quoted? If you went to get your car fixed and they quoted you one price, then billed you for double, you can sue them.

What's worse is that a lot of companies practice this type of billing on purpose. According to The New York Times, "Some private-equity firms have turned this kind of billing into a robust business model, buying emergency room doctor groups and moving the providers out of network so they could bill larger fees."

Surprisingly, Congress actually stepped up to the healthcare industry on Monday by passing the massive $900 billion, 5,600-page coronavirus relief package. Included in the bill was a law that makes "surprise" billing illegal for doctors, hospitals, and air ambulances, though not ground ambulances.

It's believed that President Trump will sign the bill into law sometime this week.

More than a dozen states, including texas and California, have passed similar bills banning this practice in one form or another.

Congress tried to pass this legislation in December, but a last-minute influx of money from private-equity forms and healthcare lobbyists scuttled the deal.

Even though it was a bipartisan issue with the support of 80% of Americans, lobbyists still made it tough to pass.

"There were a lot of things working in the legislation's favor — it's a relatively targeted problem, it resonates very well with voters, and it's not a hyperpartisan issue among voters or Congress — and it was still tough," said Benedic Ippolito, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, told the New York Times.

"It has almost everything going for it, and yet it was still this complete slog," he added.

"This was a real victory for American people against moneyed interests," said Frederick Isasi, executive director of Families USA. "This really was about Congress recognizing in a bipartisan way the obscenity of families who were paying insurance still having financial bombs going off."

Now, after the legislation passes, insurers and medical providers will have to agree on a payment rate for out-of-network services that is a fair amount based on what other hospitals and doctors normally charge. If they don't agree, they'll be sent to arbitration.

The legislation is a big win for consumers who will now be able to visit the emergency room without unknowingly being caught in a billing trap. However, we shouldn't celebrate the fact we're now protected from predatory practices that shouldn't have been legal in the first place.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

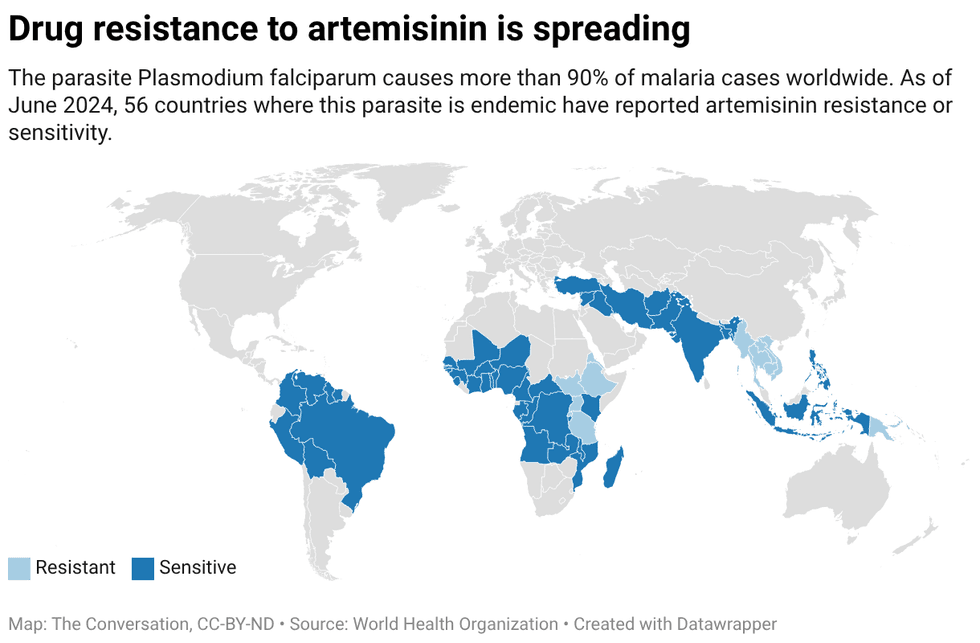

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.