Yuna Winter is a poet and artist based in a tiny village in the South Okanagan region of British Columbia. She’s also, at 27, one of the most unique and digitally savvy voices in farming.

Winter’s Twitter feed is a tangled briar patch of aphorisms about nature, reminders that the world’s ills are products of the increasing capitalism of agriculture, and mind-bending deep thoughts. But she’s also incredibly serious when it comes to permaculture, the increasingly popular style of sustainable farming that works in concert with nature rather than trying to control the land. In between her snapshots of caterpillars and esoteric tweets about her obsession with moss are lists of required reading and viewing for those interested in sustainable farming.

“I have a lot of opinions!” she shouts through the computer, over Skype. Which is precisely what makes Winter such an important voice on Twitter, and within the younger farming community camped out on social media. Her tweets often get hundreds of likes, and tweets “inspired by @yunawinter” are common amongst her followers. Maybe some of her nearly 12,000 followers will even be inspired to take up permaculture, and begin to swing agriculture as we know it away from the monocultures so common in factory farming today.

See, Winter’s radical plan to destroy the agricultural status quo includes advocating for a millennial migration to the countryside, where she thinks farming might just be the remedy for a generational malaise. Farming could use an injection of youth: according to the U.S. census, the average age of the American farmer rose from 50.5 years in 1984 to 58.3 in 2012. There is evidence that young farmers are interested, but only Rhode Island and Massachusetts have seen growth figures in young farmers.

Policymakers are starting to earmark funds to entice young farmers—Delaware has instilled a program that helps young farmers purchase land, and the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture distributes about $20 million per year in competitive grants to would-be farmers in their Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development program. But it doesn’t take a grant to make money from farming—just ask Winter.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]You can make about $80,000 on a half acre—if you know how to farm, and if you’re willing to move away from the city.[/quote]

“Explain to [millennials] that farming actually generates enough money in three years to pay off all your student loans,” says Winter, who works on the farm owned by her mom and her stepdad, Papa James, a longtime permaculturalist. “You can make about $80,000 on a half acre—if you know how to farm, and if you’re willing to move away from the city. Old retired farmers get tax bracket changes if fallow land is turned to actively farmed land. They have a fiscal incentive just to let someone farm that land.”

Once people are convinced of farming’s fiscal benefits, Winter wants to make sure that they do it right, which in her view means adhering to permaculture and sustainable farming practices—and that usually means keeping it small. According to the United States Department of Agriculture 2014 Agriculture and Food Statistics report, today’s farms are fewer and bigger. So much so, in fact, that just 10 percent of farms own more than 70 percent of the cropland in America.

Sustainable farming—among other things—means taking care of the air, soil, and water, but most of the farms on that 70 percent of cropland aren’t sustainable, and massive factory farms often pollute soil and water with fertilizer run-off. In the textbook Environmental and Natural Resource Economics: A Contemporary Approach, the authors Jonathan M. Harris and Brian Roach write that 35,000 miles of river in the U.S. have been contaminated by factory farm waste from animal production. Animals are notoriously mistreated, and many farms produce too much food to properly sanitize, meaning there are more and more outbreaks of foodborne illnesses—the spread of Salmonella is directly linked to factory farming practices.

The trick to developing a sustainable farm, says Winter, means to flip ideas about the typical farm on its head.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]This is everything that I was studying. This is how to fix all the problems that were laid out for me in all of my degrees.[/quote]

“The typical farm is backwards,” Winter says. “The typical farm says, ‘Number one, flatten all the land—rip out all of the rocks—put in irrigation. Till it really fluffy; put in all of one kind of crop to make it easy; spray it with poisons to kill the insects, weeds, and funguses that grow because you’ve been giving it too much water with your irrigation line.’ Then it says, ‘Buy expensive—like the cost of a house—machinery that you’ll need to keep up. And we’ll try and sell you more pesticides.’”

That’s the traditional farm that people imagine, and it’s hard to be enthusiastic about a farm that the farmers aren’t enthusiastic about themselves.

“Don’t do any of that!” she yelps.

Winter knows from experience the folly of modern farming. She grew up in the same town where she now farms, which had a single Subway sandwich shop, the lone option for teenage vocational opportunities. Instead, she plucked apricots in the summers with her mother in the blistering heat. She hated it, and like many rural youth, she bolted from home as soon as she got the chance, leaving to study German and Sociology at university in Vancouver.

Winter landed her first job in the city at a high-end flower shop, and it came with a hard-knock lesson in worker’s rights. For Winter, fresh off a full coarse-load of Marxist thought, the expoitative practices at the store were too much for her to handle. She describes breaking down, which led to the realization that city life wasn’t for her. By that time, Winter’s mother had moved onto the farm with Papa James, so Winter’s childhood home was vacant. Plus, her mom kept going on about this thing called permaculture.

“Everyone was saying, ‘As long as you’re not that crabby baby that wanted to leave here, you can come back,’” she says, giggling. “And then I did a Google search on permaculture, and I was like, ‘Holy shit. This is everything that I was studying. This is how to fix all the fucking problems that were laid out for me in all of my degrees. Cool.’”

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]If you are not interested in sustainable farming, doomsaying or art, there is a slight chance my twitter account may not be for you.[/quote]

It was a natural transition for Winter, who made quick study of the out-of-control capitalism that drives much of our modern food system. She rails against Archer-Daniels-Midland Co., Bunge Ltd., Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus Group—which Oxfam calls the “ABCD companies”—for messing things up royally. These companies have their tendrils in almost every segment of the agricultural business—from land ownership to the distribution of seeds to farmers—but aren’t brand names like, say, Nestlé is, and therefore are able to silently work behind the scenes. And to Winter, they represent capitalism at its most sinister, taking control away from the people in order to serve the corporation. Often, the ABCD companies will buy a specific genetically modified seed and technology packages from chemical companies (Cargill teams up with Monsanto, for instance).

“You know when Marx says you get a lot more satisfaction from building the entire chair even though the process takes longer?” she says. “When you compartmentalize each part—slamming in a nail—you don’t end up in any pride in the finished product. You did a mechanized robotic task all day. That’s kind of what a monoculture farm is.”

Seeking uniformity in their products, these companies will then lease the same packages to each of the farmers in their network.

“That’s like the worker being given a bunch of nails,” she says. “They say, ‘Farm according to our handbook,’ which is kind of like inheriting a Starbucks franchise. ‘We’ll lease you all the combines you need, and we’ll give you all the machinery. You don’t own any of it anymore. None of it’s yours. Don’t eat the soybeans. They’re not yours.’ So it’s not really ironic that farmers buy their food from the store, because they all do.”

The solutions, says Winter, lie in rebuilding farming communities. The One-Straw Revolution, a permaculture book by Masanobu Fukuoka, a Japanese farmer who taught many students how to work with the land, is considered a bible of this kind of thinking. And Joel Salatin—who wrote the influential books Folks, This Ain’t Normal and You Can Farm, and who parcels away land to interns and apprentices on his Polyface farm in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley—is a modern-day folk hero. A self-described “Christian libertarian environmentalist capitalist lunatic farmer,” Salatin apprentices would-be permaculture farmers, who graduate into what he calls “symbiotic entrepreneurs” under “stacking fiefdoms” on the farm. Which basically means he rents former apprentices land to work under the Polyface umbrella, jumpstarting their farming careers.

“I think it’s a really cool future concept of what a large acreage farm could be like,” Winter says. “And it gives people a lot more control over what they want to do.”

Winter’s dream is to set an analogue to that system up on Papa James’s farm one day, but that aspiration is a few years off. For now, the farm is on the tail end of apricot season, and just getting into plums, peaches, and green beans. She spends her weekends at farmer’s markets, where she sells fresh produce as well as fruit that is dried on a solar- and wind-powered drying deck.

“We use a lot of the overripe products, the ones that are bruised or too ripe to market, we dry them, and then we can sell them in the winter,” says Winter. “It works really nicely, and it’s small enough that he can make a nice living off of it, which is really impressive.”

Oh, and of course, she has a Twitter to tend to, and a growing follower count to cultivate and inspire. In one tweet from June, she warns, “if you are not interested in sustainable farming, doomsaying or art, there is a slight chance my twitter account may not be for you.”

Agriculture can be big and scary when it’s left to its own devices, but when someone brings it down to size, and opens themselves up to the world as Winter so often does online, it reminds us that food is grown by people. When she shares insights as to what a farm’s place in the world is in 2016, she opens up a discourse about the state of farming that just might help shape the landscape for a more sustainable future. For now, she’s content with trying to shape minds.

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/  Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

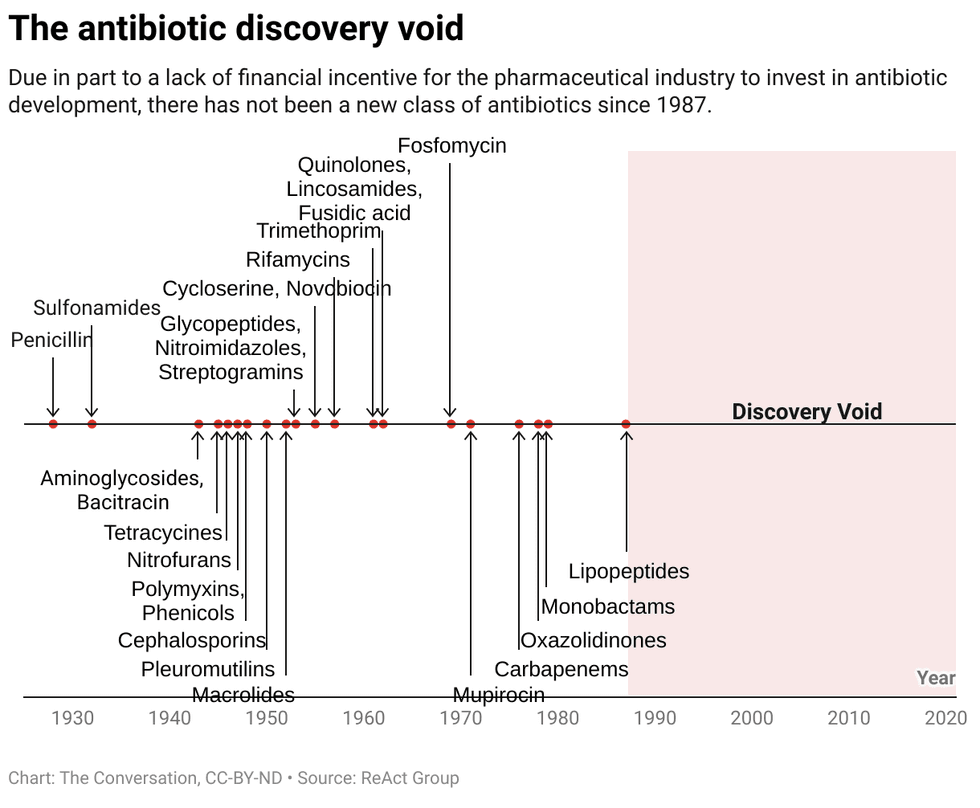

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

An envelope filled with cashCanva

An envelope filled with cashCanva Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Two penguins play by the waterCanva

Two penguins play by the waterCanva

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit  Oil production.Photo credit

Oil production.Photo credit  Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit

Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit