The year 2020 has been no stranger to suffering. In the midst of a global pandemic, widespread financial hardship and violence arising from systemic racism, empathy for others' suffering has been pushed to the front and center in U.S. society.

As society grapples to find its moral compass in a time of such hardship and strife, a critical question emerges: Whose suffering should one care about?

When you ponder who is worth feeling empathy for, friends, family members and children might come to mind. But what about strangers, or people not connected to you through nationality, social status or race?

As cognitive scientists, we wanted to understand what moral beliefs people hold about empathy and how these beliefs may shift depending on whom someone is feeling empathy for.

Empathy as a force for good

Evidence suggests that empathy – broadly defined as the ability to understand and share in someone else's experience – can be a force for good. Numerous studies have shown it often leads to altruistic helping behavior. Further, feeling empathy for a member of a stigmatized group can reduce prejudice and improve attitudes toward the entire stigmatized group.

But there has also been research suggesting empathy may contribute to bias and injustice. Studies have shown that people tend to feel more empathy for the suffering of those who are close and similar to themselves, such as someone of the same race or nationality, than for those who are more distant or dissimilar. This bias in empathy has consequences. For example, people are less likely to donate time or money to help someone of a different nationality compared with someone of their own nationality.

Neuroscientists have shown that this bias is evident in how our brains process both firsthand and secondhand pain. In one such study, participants received a painful shock and also watched another person receive a painful shock. There was greater similarity in participants' neural activity when the person they observed rooted for the same sports team as themselves.

Whether empathy has a positive impact on society or not has been the subject of a fierce debate spanning politics, philosophy and psychology. Some scholars have suggested empathy should be denounced as too narrow in scope and inherently biased to have a place in our moral lives.

Others have argued that empathy is a particularly potent force that can motivate many people to help others and can be expanded to be more inclusive.

What is largely left unconsidered is whether it could actually be our sense of what is right and wrong that limits our empathy. Perhaps many of us believe that inequality in empathy is right – that we should care more for those who are close and similar to us. In other words, loyalty is a greater moral force than equality.

The morality of empathy

In 2020, we ran a study to better understand the morality of empathy.

Three hundred participants from across the U.S. completed a study in which they were presented with a story describing an individual who is learning about global food scarcity. The individual reads about the struggles of two people in the story, one who is socially close – a friend or a family member – and another who is socially distant: for example, from a distant country. In different versions, the person in the story is described as feeling empathy for the stranger or for the friend or family member, or for both people equally, or for neither.

After reading the story, participants then rated how morally right or wrong they thought it was for this person to feel empathy in this manner.

When presented with stories in which the person feels either empathy solely for the friend/family member or the socially distant person, participants typically respond that it is more moral to feel empathy for the friend/family member. But participants judged feeling equal empathy as the most moral. Equal empathy was rated as 32% more morally right than feeling empathy for just one person in the story.

Friend or stranger?

Although this study suggested that people believed it more moral to have equal empathy, it left certain questions unanswered: What was behind the perceived morality of equal empathy? And would this pattern hold if people were judging their own feelings on empathy?

So we ran a follow-up study with a new sample of 300 people. This time we changed the story so that it was from the participants' own perspective, and the two people in need were people they personally knew – one being someone close to them, the other an acquaintance. We also added endings to the story, so that participants could now also feel empathy for both people but to different degrees.

The results were remarkably similar to the first study: Feeling more empathy for one's close friend or family member was seen as more moral. But most notably, feeling equal empathy for both people was again judged as the most moral outcome.

Where to go from here?

In a moment when fostering a culture of caring for those who are different seems challenging, our research may offer some insight and perhaps hope. It suggests that most people believe we should care about everyone equally.

With the right approach, this belief in the morality of equal empathy may even translate to real changes. Recent work has shown that empathy can be increased based on one's motivation and personal beliefs. For example, participants who wrote a letter about how empathy can be grown and developed showed improvements in their ability to recognize others' emotions, a major part of empathy.

We are undoubtedly living through an age in which people are divided by race, nationality and political affiliation. But we are all human beings, and we all deserve to be cared for on some level. Our research provides evidence that this principle of equality in empathy is not some obscure ideal. Rather, it is a tenet of our moral beliefs.

This article first appeared on The Conversation. You can read it here.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026. Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

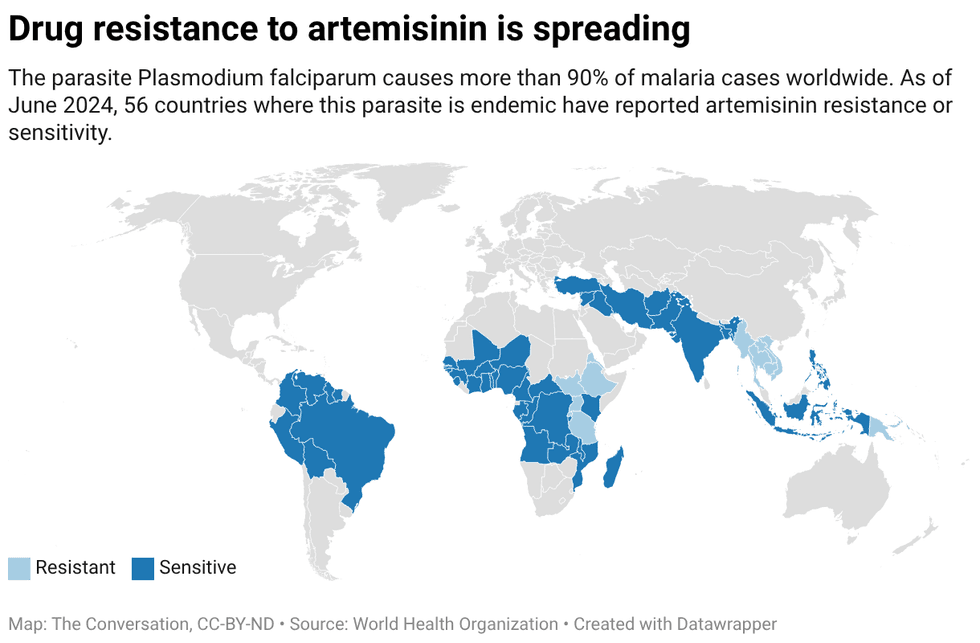

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with