When the Final Four tips off this weekend, it will cap off one of the greatest events in all of sports: the NCAA Tournament. For the last couple weeks, the sports world has been consumed by bracket busters (Duke getting bounced in the second round), buzzer beaters (Luke Maye’s heroics for North Carolina against Kentucky) and Cinderella stories (South Carolina making its first ever Final Four). It has been sports-fan nirvana.

It’s pretty great for the NCAA too. A decade ago, media rights fees for the whole tournament were $509 million, while this season the organization will rake in $761 million from CBS and Turner for the right to broadcast the three weeks of games. This one event pretty much keeps the NCAA afloat.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]They don’t make a profit. Every dollar put in, they piss away a dollar and a half.[/quote]

So the fans are happy, the NCAA is flush with cash, and so the schools must be feeling great about it too, right? Wrong. You’d think NCAA athletics would be a boon for the schools involved, but you’d be wrong. “They don’t make a profit. Every dollar put in, they piss away a dollar and a half.” says Murray Sperber, a visiting professor at the University of California, Berkeley.

Sperber would know. For nearly three decades, he has studied the effects of big-time sports on the academic side of the universities that participate. His findings aren’t pretty. All this money thrown at sports, he contends, has drained resources from schools and students.

In his book, Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports Is Crippling Undergraduate Education, Sperber says the rot goes deeper than mere debt. Playing off the Roman Empire’s “bread and circus”—where politicians cynically provided food and festivals to keep the populace happy and distracted—he argues that colleges are doing the same with their undergraduates. Students have become the universities’ customers, but instead of teaching them, they keep them satiated with partying and big-time college sports. When The New York Times reviewed the book in 2000, there was the ominous line, “It is hard to read Sperber's book without having a sinking feeling about the future of American culture.”

Recently, when we reached out to Sperber (17 years after Beer and Circus had been published) he told us “the bad guys won” in the battle over the universities vs. their athletic departments. So we spoke with him to find out how big-time college sports is hurting education, why he thinks the bad guys prevailed, and what he thinks could be done to help.

How are athletic departments hurting their own schools?

Take the Pac-12. It has expanded, it has a TV network, and there is a huge amount of money pumped into it. Turn on your TV and you’ll see pretty full stadiums and arenas, but because they play so many sports, they’re losing money. Berkeley is losing, they admit, $12 million year. But it’s higher if you did the books, honestly. At the end of the year, when universities have to balance their books, they take money that could go to academics, like for student scholarships, and use it to cover the athletic department deficit.

And it’s worse than when you wrote Beer and Circus?

College sports has been hugely amplified, with huge amounts of money pumped into it. And there’s more pressure on coaches to win, which means that athletes aren’t getting to class any more often now than they did before, and in some cases less. Also, there is a minority of the alumni, and people who aren’t alumni—boosters—who root their hearts and give money to the athletic department. They’re vociferous about the sports they support. Put all this together and it reaches a tipping point, and so it’s fair to say that in 2017, the bad guys have won.

Even with all this money coming in, athletic departments are still in the red?

When you build a building, the donors will put up money for a weight room, but they never put up money for the maintenance of a building. Even Phil Knight’s buildings at Oregon. You’re losing money on all of this.

Why have schools allowed this to happen?

Public universities were created to educate the kids in the state where they were set up, but it has really drifted away from that. The thesis of Beer and Circus is that because colleges’ most regular source of revenue is tuition and fees from undergraduates, they want as many of them as possible. But the question becomes what do we do with all these undergrads once they get here? Supplying them with beer and circus becomes a pretty easy solution for a lot of schools.

Rather than spend a lot of money on undergrad education, they’ll almost consciously neglect it. That’s clear when you look at metrics like class size and earning power of graduates at many large public schools. Yet, they certainly want the dollars from the students, and they realize the students, a great many of them love beer and circus. They claim they’re unhappy about the party scene, but it goes on. Indiana has encouraged many students to move off campus, so the school is not responsible for their drinking.

So are sports the cause or the symptom of what’s wrong?

Neglecting undergraduate students is part of a much larger problem in American higher education. A generation or two ago, when I was an undergraduate at Purdue University. I received a really quality education. I had freshman English with a class of 15 students with a full faculty member. I got a wonderful education because of that. I taught freshman English at Indiana University with classes of 150 students. If I learned 20 to 30 students’ names, that was a good semester.

The neglect has gone on for a while, but it’s reached a point where, but it’s reinforcing the haves and the have-nots in this country. If you get a good science education, you’ll get a good job. But if you get a lousy education and your skills aren’t very high, you may get a job as a manager at Starbucks.

Who are the bad guys?

The real bad guys are the university administrators, who bought into the kind of fiction that college sports is wonderful and that it would do great things for the school and that March Madness would help. They should have valued the academic side of the schools more, but just allowed the athletic side to get bigger and bigger and bigger.

How did schools come to buy into this fiction?

In many ways, Notre Dame and their football coach Knute Rockne invented big time college sports in the 1920s. They saw the media potential in it. When radio came along, other schools sold their rights; they gave away their rights all over the country because they wanted to reach fans everywhere. They were a poor Catholic school before Rockne came along, but big time college football helped Notre Dame get them through the Depression. The school, to this day, makes a lot of money from college sports.

With that model in mind, many schools imitated Notre Dame. But it’s like Microsoft, Google, or Apple, if you’re there first, and have the best idea, you’re going to do really well and there are going to be many imitators of your formula. Many of those imitators are going to go belly-up, and others will limp along adhering to the formula for no other reason than Apple, Microsoft, and Google did it that way. Administrators bought in because they truly believed they’d be the next Notre Dame.

A number of schools in more remote geographic locations did succeed with athletics. Like the University of Nebraska has done well and money because there’s nothing else in the whole state of Nebraska. And Indiana and Kentucky did it with basketball. There are enough Nebraskas in football and Kentuckys in basketball to keep the myth alive that sports and March Madness help the university.

But even if they don’t make money, don’t college sports help promote the school? A good March Madness run can increase applications.

I’ve done research on this. Administrators will say, ‘Yes, we’re losing money on sports, but the publicity can be fabulous, just look at the attention we’re getting during March Madness.’ In my research, I called up admissions offices and I asked them whether the extra cohort of people applying had the same GPA and SATs as their regular admission. Was it better or worse? They’d all say, ‘We’ll get back to you.’ In almost every case, they never did. Common sense tells me that if the cohort had higher SAT scores, they would have gotten back to me. People have done follow-up research, and they used public records acts to look at admissions scores and, best case scenario, they’re about the same, but very often worse.

Others have done studies on these cohorts of students who enroll after sports success and found that they tend to join Greek organizations, get arrested for alcohol consumption, and various other things. Which raises the question, if the extra cohort exists and they’re the party animals, what good is it doing for schools?

Do sports have a place at universities?

Yes, in the Division III model. If you have a kid who wants to play sports, I tell people to think about Division III, where they’re creative with grants for athletes, but they’re regular students. They play their sports about 20 hours per week, and it helps focus their lives and they get a good education. But I know you’re not going to put the genie back in the bottle. Big time is just going to get more big time.

Are there reforms schools can adopt to at least make a bad situation better?

I don’t want to sound too bleak, so I will say this, athletic departments are getting much better at supplying tutoring than in the past. For instance, if an athlete leaves without a degree for a pro career and that ends in a few years, Berkley encourages those people to come back to get that degree and works very hard with those athletes. You could call that a Band-Aid solution, but for the individuals involved, it’s really positive. I’ve had a number of athletes in that situation in my classes and they’re very good students. They bring the discipline from sports to class, and when they can truly devote that time to their studies, they’re really good. That’s a new phenomenon and a positive one.

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

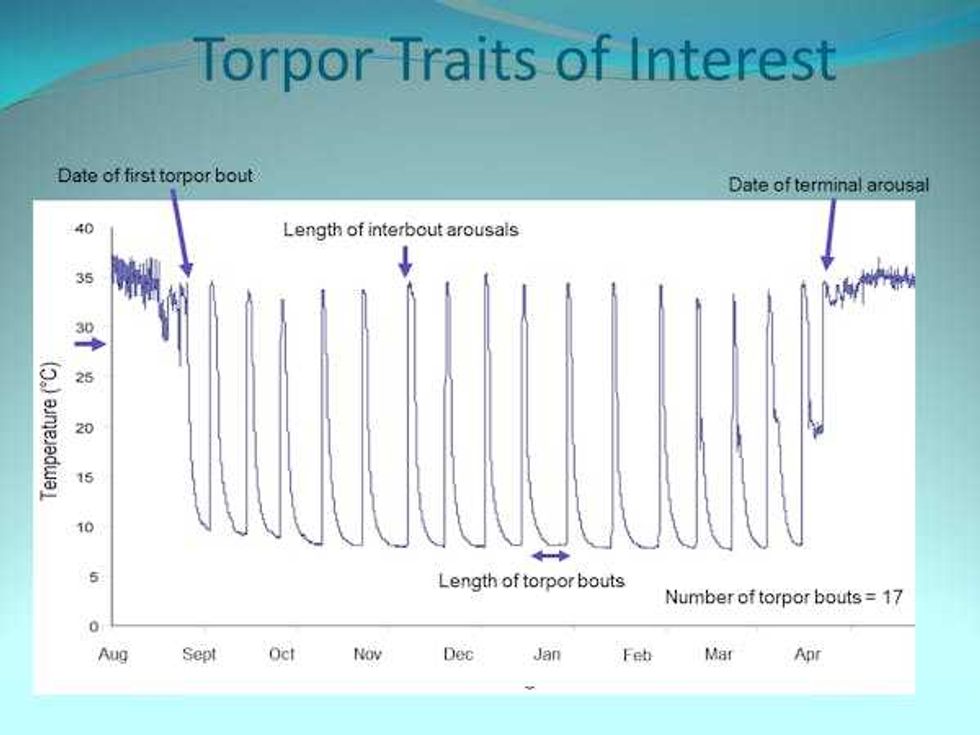

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva  A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

People voting. Photo credit:

People voting. Photo credit:  Young women rally. Photo credit:

Young women rally. Photo credit:  Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Winter weather.

Winter weather.

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from  A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from