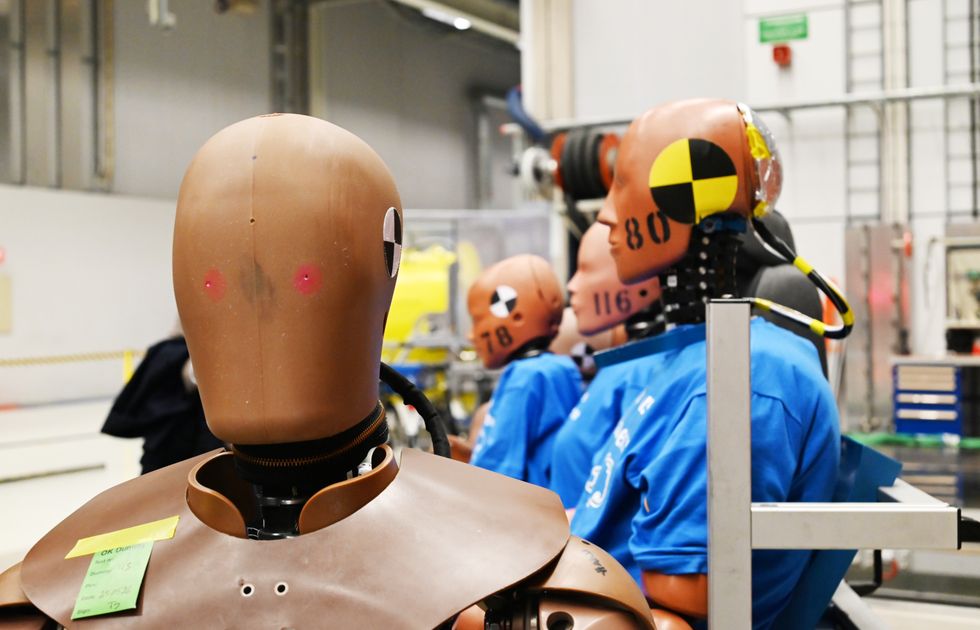

From a window high above, I watch intently as two bright orange cars crash into each other. I’m expecting it, but the sound is still jarring. We’re at the Volvo Cars Safety Centre in Gothenburg, Sweden, and in a room of experienced automotive journalists, I’m the only one who gasps. The cars smash loudly, glass and metal breaking and cracking onto each other. I watch as the airbags explode, covering the crash test dummies in pillowy, white clouds. I wonder about the female crash test dummies in particular because, historically, they weren't always there.

Crash test dummies were first used by the automotive industry in 1968, after car crashes around the country had become notably deadly–the United States Department of Transportation’s Bureau of Transportation Statistics shares that 1966 alone brought 50,894 highway deaths. Crash test dummies were invented by physicist Samuel Alderson, who also studied with J. Robert Oppenheimer, and they were originally used in the 1940s by the Air Force.

The first use of crash test dummies in cars featured entirely male figures. While there were female crash test dummies as early as the 1970s and 1980s, according to Dr. Lotta Jakobsson, Senior Technical Specialist, Injury Prevention, at Volvo, they were only of one size: a small female. According to Consumer Reports, automotive regulators “asked for a female dummy in 1980, and a group of automakers petitioned for one in 1996, but it took until 2003 for NHTSA [National Highway Traffic Safety Administration] to put one in the car.” NHTSA currently has two female crash test dummies in use, the “5th Percentile Adult Female,” who represents a female who is four feet, eleven inches high and 108 pounds, and the “Small Adult Female,” who is also four feet, eleven inches, but 97 pounds.

In 2022, the first average female crash test dummy, SET50F, arrived at a height of five feet, three inches and a weight of approximately 137 pounds. Created by Professor Astrid Linder of Sweden, she was in development for 20 years. Still, testing the SET50F is yet not required for safety certification by car manufacturers. Testing is only required on the aforementioned small female crash test dummies, which “represent the 5% smallest part of the population in the 70s of women,” Dr. Jakobsson says. She adds that while these dummies have still been essential in making cars safer, more information is always better. But even with more dummies, Dr. Jakobsson continues, the information available is limited to what can be gleaned from each figure’s exact size and shape.

For example, when it comes to studying front and rear end impact, the possibilities of understanding were extremely limited for a long time. “There were no other tools than the mid sized male for rear-end impact,” Dr. Jakobsson says, adding that because there was no small female dummy for rear-end impact, you’d have to use the female frontal impact dummy, which was not as effective. “That's not really good. She's not as good doing rear-end crashes. She's trained for frontal crashes,” Dr. Jakobsson says. “More tools are better than fewer tools, whether you call them men or women.”

Despite the tools at hand, there are more female drivers in the U.S. than male drivers, according to Consumer Affairs. “Licensed female drivers have outnumbered licensed male drivers since 2005,” they wrote, adding that “in 2022, there were just under 119 million licensed female drivers and just over 116 million licensed male drivers.” Female drivers are also potentially in more danger. According to Consumer Reports, “a female driver or front passenger who is wearing her seat belt is 17 percent more likely than a male to be killed when a crash takes place,” and “for a female occupant, the odds of being injured in a frontal crash are 73 percent greater than the odds for a male occupant.” If there are more female drivers who could be at greater risk of injury in a car, how can crash test dummies be used to protect them?

For Dr. Jakobsson, with this question comes another. “Obviously cars should be assessed then developed equally safe for men and women, definitely,” she says, acknowledging that making cars safer for women was delayed across the automotive industry as a whole. “The question is, then, is it the crash test dummy doing that?” While Volvo uses crash test dummies, as I saw when I visited their Safety Centre, they also rely heavily on real world data to craft vehicles to be as safe as possible for women and men alike; in doing so, they have decreased the gap between safety for men and women in their own vehicles. Another factor that can help is introducing the more regular use of virtual testing with human body models—a crash test dummy, as we’ve seen, can take some 20 years to produce, and even more time to be incorporated into regulatory testing. And while a virtual model still takes time to produce, it’s significantly less time than a physical crash test dummy. “It's not a quick fix. It takes a while to do that, of course, but it doesn't take decades,” Dr. Jakobsson says. “That's what will make a difference with respect to a car manufacturer perspective, and that's when they can use different sizes and make a robustness based on that.”

There are even more changes afoot. As AP reported, law student and activist Maria Weston Kuhn founded the nonprofit organization Drive US Forward after being in a violent car accident herself–though her dad and her brother sat at the front of the car during a frontal crash, they experienced minimal damage, while Maria and her mom endured significant physical trauma from the backseat. She wanted to advocate for women’s vehicular safety, and now the organization hopes to “raise public awareness and eventually encourage members of Congress to sign onto a bill that would require NHTSA to incorporate a more advanced female dummy into its testing,” AP shares.

An extension of advocacy for women behind the wheel, beyond female crash test dummies already in use, could have wide-ranging benefits across the automotive industry. “It's all about understanding who is most vulnerable,” Dr. Jakobsson says. “If you can help that person and protect that person, then the other ones will be protected as well.”

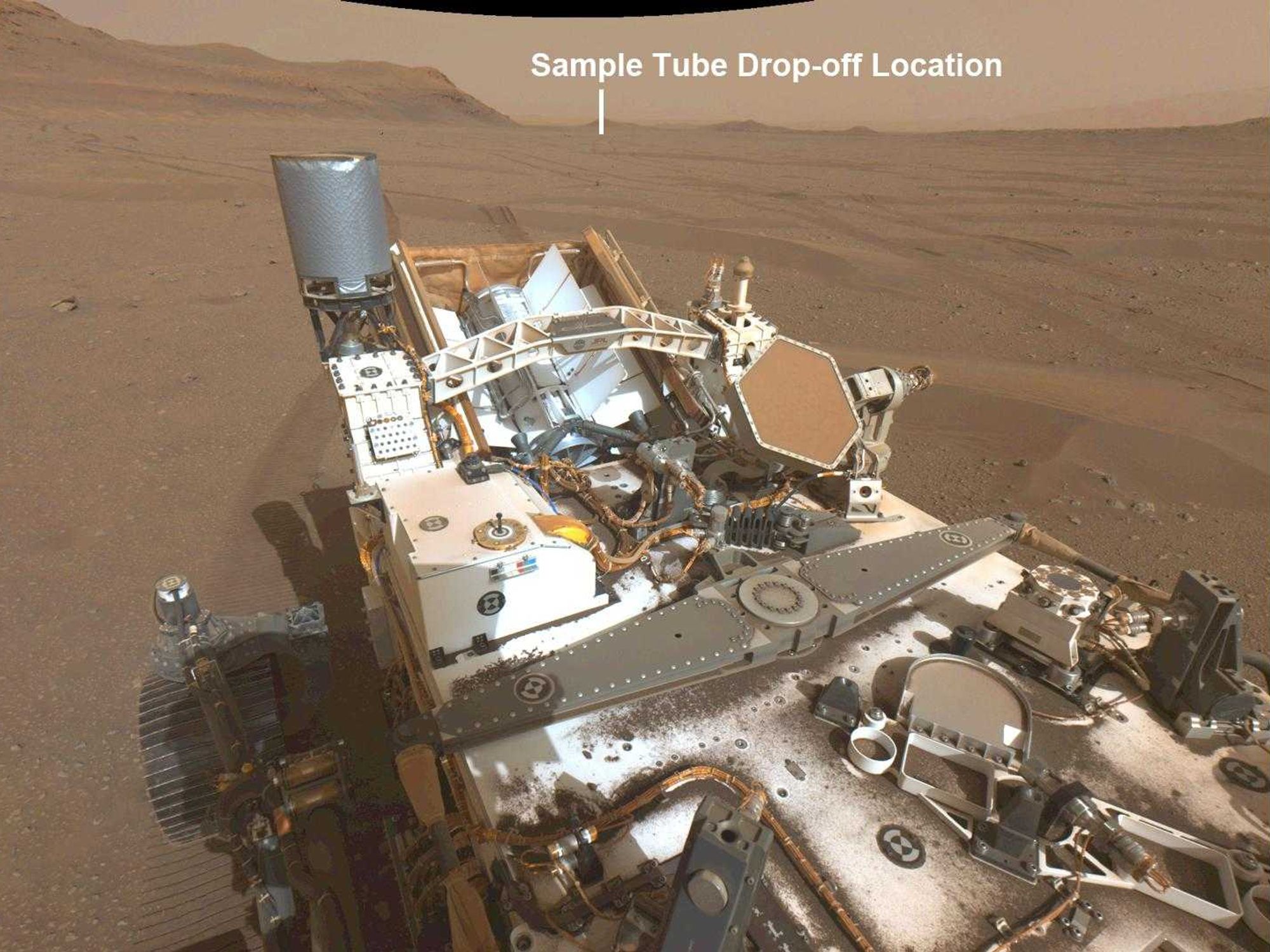

Images from Mars from NASA's Perseverance Mars rover.NASA/JPL-Caltech/

Images from Mars from NASA's Perseverance Mars rover.NASA/JPL-Caltech/  Eye surgery.Photo credit:

Eye surgery.Photo credit:

Superstructure of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, 2007

Superstructure of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, 2007

Gif of Pinocchio via

Gif of Pinocchio via

Floating gardens with solar panels. Image from

Floating gardens with solar panels. Image from  Petroleum jelly. Image from

Petroleum jelly. Image from

Man standing on concrete wall.Photo credit

Man standing on concrete wall.Photo credit  The Pantheon in Rome and Hong Kong at sunrise.Photo credit

The Pantheon in Rome and Hong Kong at sunrise.Photo credit  Windmills and green grass.

Windmills and green grass.  Time lapse of blue skies over a solar field.

Time lapse of blue skies over a solar field.

3D televisionImage via

3D televisionImage via  Standing on a hoverboard.Image via

Standing on a hoverboard.Image via  Never ending potato chip kkaleidoscope.

Never ending potato chip kkaleidoscope.  Woman using VR goggles outdoorsImage via

Woman using VR goggles outdoorsImage via  The Las Vegas Sphere

The Las Vegas Sphere