Most of us know the difference a good teacher makes in the life of a child. Many global institutions working to improve access to education, such as the United Nations, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and Education International agree that “teacher quality” is the critical element in whether or not an educational system succeeds.

The United Nations has even called for

“allocating the best teachers to the most challenging parts of a country and providing teachers with the right mix of government incentives to remain in the profession and ensure all children are learning, regardless of their circumstances.”

It is clear we need good teachers, but just what makes for “teacher quality”? And can quality be systematically improved by public policy?

For 30 years I have been studying cultural expectations for what makes a good teacher, beginning with field work in a Tibetan refugee school and an ethnographic study of Japanese and American public schools conducted some years later. More recently, my colleague Alex Wiseman and I have been working on what researchers from around the world consider to be “teacher quality.”

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]A 'high-quality' teacher from Japan would likely feel incompetent in a U.S. school, even if she was fluent in English.[/quote]

The consensus is that teacher quality entails much more than just the way teachers deliver lessons in the classroom. Teacher quality is strongly affected by a teacher’s working conditions. Teachers working long hours, with low pay, in crowded schools cannot give each individual student the attention they need.

Simply raising the requirements for teacher certification, based on what has worked in some high-performing countries, is not effective. An effective policy requires changes at the level of teacher recruitment, teacher education and long-term support for professional development.

Quality is more than certification

Around the world, more than a dozen nations have recently engaged in efforts to rapidly reform their teacher education and certification systems. The United States, along with nations as diverse as France, India, Japan, and Mexico, has sought to improve its educational system by reforming teacher certification or teacher education.

Usually, governments try to do this by passing laws that list more requirements for teachers to get their teaching certificate or license. Often they look for models in countries that score well (such as Finland, Singapore, or South Korea) on international achievement tests like Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) or Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA).

It is true that a teacher’s qualifications, experience, personality, and instructional skills all play a role in contributing to “quality.” Teacher quality covers what teachers do outside the classroom: how responsive they are to parents and how much time they put into planning lessons or grading papers. Teaching certificates can make a difference toward ensuring teacher quality.

But that does not make for an effective policy. And here’s the problem: One, merely focusing on standards like certification is not enough, and two, the effect can vary by grade level or because of student background—so borrowing models from other countries is not the best strategy.

In the United States, for example, a key part of the important legislation No Child Left Behind was to put a “qualified teacher” in every classroom. The law emphasized certification, a college degree, and content specialization, but failed to identify teachers who knew how to implement reforms and who promoted critical thinking skills in their classrooms.

The most recent law addressing teacher quality, the Every Student Succeeds Act, had to roll back these requirements, allowing each state in the United States to experiment with different ways to identify quality teaching.

The law allows states to experiment with different types of teacher training academies and with measures of student progress other than just standardized tests.

Goal of American teachers different from Japanese

Moreover, teacher quality is context dependent: What works in one country may not work in another, or even for another group of students.

Let’s take preschool or early elementary teachers as an example. At this age, many parents would look for teachers who are warm, caring, and understand child development. But this, as we know, would change for high school students.

In high school, especially in college preparation courses, students and parents would expect teachers to focus on the lesson. The quality of their teaching would be judged by how well their students score on tests, not how well they are developing socially or emotionally.

Other than the age of the student, goals of the educational system would matter too. For example, American, Chinese, and Japanese teachers take very different approaches to caring for small children and helping them learn basic academic skills. In their book, Preschool in Three Cultures, educational anthropologist Joe Tobin and others showed that Japanese preschool teachers are comfortable with classes of 20 students, and tend to tolerate noise and disorder that most American teachers would find uncomfortable.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Unequal access to teachers as one of the greatest challenges facing the U.S.[/quote]

By contrast, American teachers place great emphasis on one-on-one interactions between children and adults, especially in helping children learn to express their feelings. It is possible that a competent, “high-quality” teacher from Japan would likely feel incompetent and confused in a U.S. school, even if she was fluent in English.

Countries have their own challenges

That’s not all. National conditions impact teacher quality. In some nations, it is a struggle to retain good teachers and distribute them evenly.

For example, many low-income countries face challenges related to poverty, illness, and labor shortages that create teacher shortages. Peter Wallet, a researcher at UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics, shows that in many countries, national governments struggle to find enough teachers to staff their schools. He writes:

“The impact of HIV and AIDS in Tanzania for example meant that in 2006 an estimated 45,000 additional teachers were needed to make up for those who had died or left work because of illness.”

The loss of so many teachers places many children at risk of having no access to quality teachers. This basic lack of qualified teachers has been identified by UNESCO as the major barrier to providing access to quality education for all the world’s children.

Even in wealthy nations, sometimes the most qualified teachers are concentrated at certain schools. For example, in the United States there is a very unequal distribution of teachers between high- and low-income school districts. Scholar Linda Darling-Hammond sees this unequal access to teachers as one of the greatest challenges facing the United States.

The point is not to borrow

The fact is that teaching is complex work. Teachers must build trust, increase motivation, research new methods of teaching, engage parents or caregivers, and be adept at the social engineering of the classroom so that learning is not disrupted.

Effective teacher policy has to have at least three levels: It must provide clear goals for teacher education and skill development; it must provide “support to local institutions for the education of teachers”; and it must address national demands for high-quality education.

And in order to develop teacher quality, nations need to do far more that “borrow” policies from high-scoring nations. Nations can learn from one another, but this requires a systematic exchange of information about sets of policies, not just identifying one promising approach.

The International Summit on the Teaching Profession, an annual event that began in New York in 2011, is one example of this kind of global exchange that brings together governments and teacher unions for a dialogue.

To be effective, reforms need to have the support and input of teachers themselves. And, national and global leaders need to create more ways for teachers to provide suggestions, or criticism, of proposed reforms.

A high school senior shows how to unlock a magnetic pouch that holds her smartphone at University High School Charter in Los Angeles in March 2025.

A high school senior shows how to unlock a magnetic pouch that holds her smartphone at University High School Charter in Los Angeles in March 2025. An eighth grader unlocks her cellphone from a pouch at Mark Twain Middle School in Alexandria, Va., in March 2025.

An eighth grader unlocks her cellphone from a pouch at Mark Twain Middle School in Alexandria, Va., in March 2025.

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

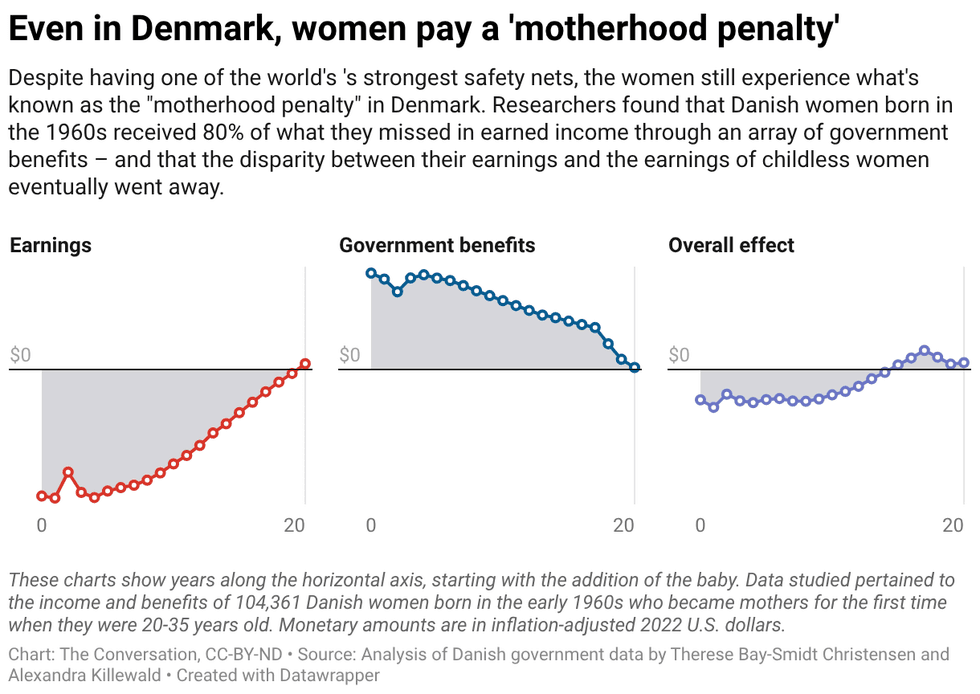

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit: