When the unrest in Libya first began almost four years ago, newspapers and magazines reported about the explosion of art in the streets of Benghazi and Tripoli. Graffiti and murals covered every inch of bullet-ridden surface, lending the streets a visual vibrancy that matched the revolutionary fervor in post-Gaddafi Libya. Art exhibitions were being held for the first time. The international press regularly gave shout outs to Libyan artists, like sculpture artist Ali Wakwak and ceramicist Hadia Gana. International organizations like the Goethe Institute and the British Council invested in efforts to promote local cultural production, funding literary and arts events in Libya.

The passions that fuelled the revolution were soon replaced by disillusionment with the stagnating democratic process. However, a number of institutions have emerged recently to rekindle the creative energies unleashed by the 2011 uprising. Among them is Noon Arts, an arts collective helmed by Najlaa Alageli and Nesreen Gebreel, two Libyan women who’ve spent much of their lives abroad.

“I was really struck by, not just the firearms, but, to me, what was a cultural revolution,” said Gebreel. “All this burgeoning talent was just bursting out. All the street art, all the music, in the Benghazi headquarters, that’s all you could see.”

Many of the circumstances that kept Libyan art from flourishing under the Gaddafi regime and, prior to that, under the Italian colonization, persist today: a dearth of public and private art institutions, a lack of art education and the almost nonexistent art market. With no real institutional support, Libyan artists remain largely unknown, not just to the local public, but to the world at large. It’s part of the reason Alageli and Gebreel started Noon Arts.

“I go to exhibitions in London, and I see the Lebanese, I see the Palestinians, I see the Egyptians, everybody,” says Alageli. “And then I see nothing of Libya.”

Libya’s exclusion from the global consciousness around the visual arts can be traced back to the Italian colonization. The Italian authorities did little to encourage creative pursuits in Italy and even prevented most Libyans from pursuing secondary education.

“It was [Italy’s] fourth shore, and it was mostly for the land, to grow food for their starving people in Sicily,” says Hadia Gana, a conceptual artist from Tripoli who is represented by Noon Arts. For the Italians, Libya was culturally bereft—a perception that continues to pervade Western perspectives. In his 2011 book, The Arabs: A Journey Beyond the Mirage, journalist David Lamb disparagingly wrote of the country: “Take away the oil and the guns and Kadafi would be the leader of a cultural backwater ranking alongside the Dijiboutis and the Somalias and the other forgotten nations of the world.”

The political and social repression of the Gaddafi regime subdued artistic expression, especially for artists who were pursuing conceptual styles.

“There were art exhibitions and that sort of thing but it was very much controlled by the government,” says Gebreel. “So it was all propaganda.”

Says Gana: “You couldn’t go very clearly against the government and you couldn’t do things that were clearly nude, clearly sexual. Because you have the political taboo and the social or cultural taboo.”

Grafitti artist Aymen Ajhani, who began spraying his paint on Libya’s white walls anonymously in 2009, challenged these taboos head on with his signature stencil, a Hand of Fatima with the middle finger extended upwards. The Hand of Fatima, or Hamsa, is a hand-shaped amulet popular in the Middle East. Ajhani’s modern rendering of it was politically charged, a visual “screw you” to the powers-that-be. Ajhani had exploited an image very closely associated with Islamic mysticism and transformed it into a lewd gesture.

“It was getting crazy, because people were asking [about] who was making it,” says Ajhani, “They felt that I was insulting them.”

Ajhani encountered other challenges as well. He couldn’t purchase spray paint without showing his I.D., making it easy for authorities to track down dissenters who use the paint for anti-government art.

The Gaddafi government did, however, give Libyans unprecedented educational opportunities. Bashir Hammouda, Ali Wakwak, and Ali Gana, Hadia Gana’s father, are part of what is referred to by Libyan historians as the “first generation” of Libyan artists. They were artists of the 1970s who traveled abroad on scholarships and received their arts education in places like Rome and the U.K., where they were exposed to new alternative styles and mediums. Gana says part of the problem was lack of demand. Art was a luxury most Libyans could not afford.

“You didn’t have galleries. You had like, two, and from time to time, you had another because they can’t sell,” says Gana. “There’s no art market, that’s the main problem.”

The 2011 uprising provided Libyan artists with a market for the first time. The overthrow of the Gaddafi government meant no more institutionalized censorship. People exercised a new freedom of expression and produced adventurous forms of art. Ali Wakwak, who is also represented by Noon Arts, utilizes the remnant materials of war – bullet cases, military gear, gun barrels – to create sculptures. Gebreel says the Noon Arts collective has provided the artists with something else they have never had before: a platform for international critique.

“You can’t really improve unless you have critique,” says Gebreel. “We also have to work with artists that are looking to grow as well, whatever age they are.”

Noon Arts held their first exhibition in Tripoli, at the building of a popular architectural firm. More than 500 people attended, among them ambassadors and diplomats. It was a jubilant event that not only provided local artists with a platform to display their work, but a space where ordinary Libyans could view it for the first time.

“It created a lot of buzz and people were quite happy, because for 42 years there’s hardly been any exhibitions that are not attached to some kind of political propaganda,” Alageli says.

They’ve held several exhibitions since, including a wildly successful one in Malta where sculptor Mohammed Bin Lamin showcased sculptures he had produced from the remains of war. “To bring the artwork from Libya is a lot of work,” Alageli says. “We had sculptures that were made out of bullets. You need diplomatic passes to transport them.”

Despite the continued unrest in Libya, Alageli and Gebreel are planning a 2015 exhibition at London’s Shubbak Festival, which celebrates contemporary Arab culture. Ajhani will be there as well, showcasing his street art. Meanwhile, Libyan politics have once again descended into chaos. Violence characterizes life in the cities, while rival political powers have been jockeying for control through militia battles that take place in civilian areas. There is no clear governing power. The schools have been closed and there are constant electricity blackouts. Many artists, like Ajhani, who now works out of Copenhagen, have been driven out. But Alageli and Gebreel say that art is more important now than ever.

“’[Art] gives you hope, it gives you positivity,” Gebreel says. “People always need positivity. Sometimes, you know, if you look at history, the most creative times are during wars or during recessions.”

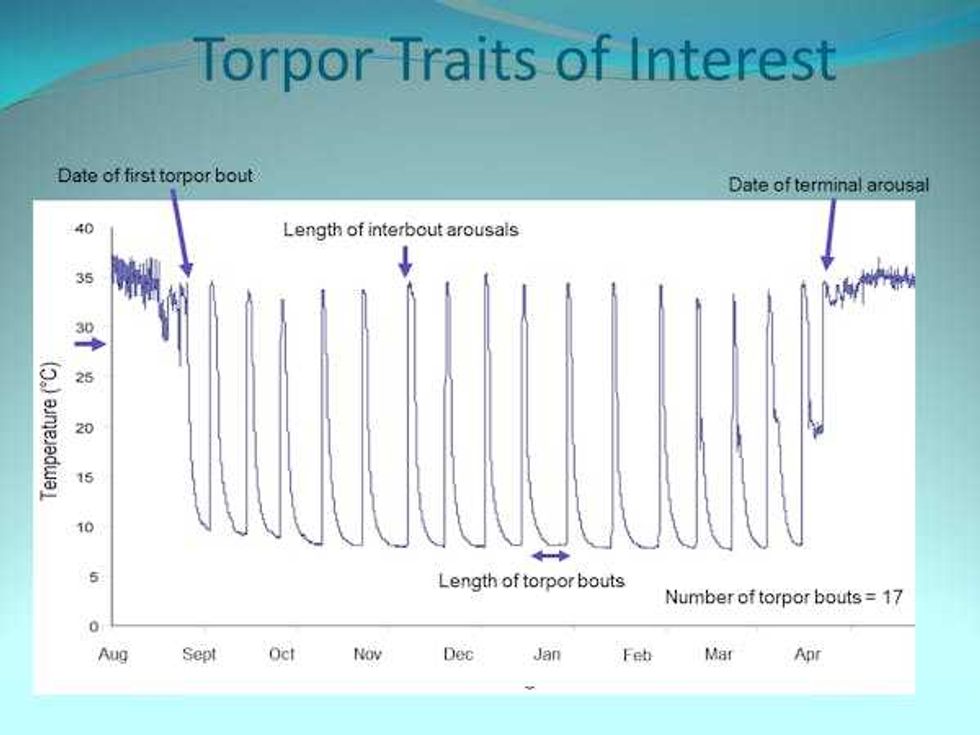

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva  A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

People voting. Photo credit:

People voting. Photo credit:  Young women rally. Photo credit:

Young women rally. Photo credit:  Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from

Honorable J. Cedric Simpson at work in the courtroom.Image from  A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

A close up of Judge Simpson.Image from

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva

Siblings engaging in a pillow fightCanva