Over the last four decades, artist, photographer, and filmmaker Laurie Simmons has charted the female psyche through made-up worlds and scenarios that challenge our perceptions of reality. Perhaps best known for her dollhouse works, prominently featured in daughter Lena Dunham’s breakout movie Tiny Furniture, her newest series brings those explorations online, from the world of Kigurumi cosplay to the real doll community—women who alter themselves to look like Barbie, baby dolls, and Japanese anime characters through makeup, clothes, and even cosmetic surgery. In Laurie Simmons: How We See, opening March 13 at the Jewish Museum, Simmons unveils seven new works that play on archetypal fashion model imagery, with an unsettling twist. Posed in front of a school photo-type backdrop, and cropped from the shoulders down, the girls all have an “uncanny, alien gaze” achieved by their painted on “preternaturally large, sparkling eyes” to create a humanoid effect—a technique borrowed from the cosplay community. For How We See, Simmons went beyond the voyeuristic explorations that usually accompany coverage of these so-called doll girls to question notions of beauty, identity, and persona. In an era when social media platforms like Facebook and Instagram permit endless morphing, retouching, and temporary versions of the self, Simmons wonders just how real reality is now.

Recently we were able to catch up with Simmons at her home studio in Connecticut where we discussed role play, Second Life, and love in the time of Tinder.

GOOD: Thank you so much for speaking with us so early on a Saturday morning! Though we were only able to preview a few images, the whole series has been fascinating.

It’s interesting because I’m actually shooting what will be the last two on Monday. I don’t think I’m completely done, but I’m excited to be able to put a little closure on [the series] for this show. I’ve been known to work up to a week before an exhibition. Once I shoot, it has to be printed and mounted and framed. There are galleries you go into and you smell the fresh paint, but it’s hard to understand, when you see a photo, that it was made so recently.

I’m not the person whose work comes in late. But I always like to mix it up and give more during an installation, so I always have extra things to play with when I’m hanging the show.

Do you think that adds to the organic nature of the show?

I think the thing about being an artist now—particularly a photo-based artist with Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, social media, and the internet—is that photography is so ubiquitous. A majority of people just see my work online and forget about the experience of actually taking the image, making it into an object, then taking that object and figuring out how to install it in a space. And that’s one of the things that separates a number of visual artists from the “visual makers” in the big wide world. I rarely ever talk about this, but not enough is discussed about the fact that these [works] really exist in the world as objects, and when I’m making an art show I’m having the images speak to each other in some way and interact. That’s a huge part of what I do. And I say it’s probably true of a lot of artists that work the way I do. It’s the end of something, or the revisiting of something we’ve been focusing on for a long time. So this conversation is kind of significant.

It seems that with How We See and your doll girl community works you’ve really plunged headfirst into internet culture. What did you find most intriguing in your research?

Over the span of my lifetime it seemed like [the internet] just happened so fast. I’m still sort of buzzed by the amount of information I can access. I spend more than a little time imagining myself as a teenager with access, and I really think I never would have come out of my room. I would get these obsessions, even in my early 20s, where I would, for example, need to know everything you could possibly know about gypsies. And I would go to the library, or try to find books, or magazine articles about it. I was constantly frustrated by the questions that couldn’t be answered. But this had nothing to do with school. I had no use for school (laughs). But I just think, number one, I would never have left my room because I would have been searching for information and, number two, I probably would have just stalked my boyfriend online. I just always wanted to know stuff that I couldn’t find out. And I can’t believe how much stuff is available.

The internet is definitely a rabbit hole. You start Googling something simple and end up somewhere entirely different.

There’s a way that the internet lends to synching information that suites the ADD brain, which I strongly believe I have. It sort of intuitively leads you to this, and then to that, and it’s a searching sequence that really works well for me. I really love it, and I feel like I spend way too much time in front of my computer. I have another friend who’s older who said, “when I started exploring people who have sex with chickens, I realized I’d really gone too far.” She really had to just shut it down. She definitely went to the dark side. I feel like I spend too much time online, but I don’t feel like I’ve gone to any place that’s dangerous.

Is that how you found the online doll girl community? Just wandering the internet?

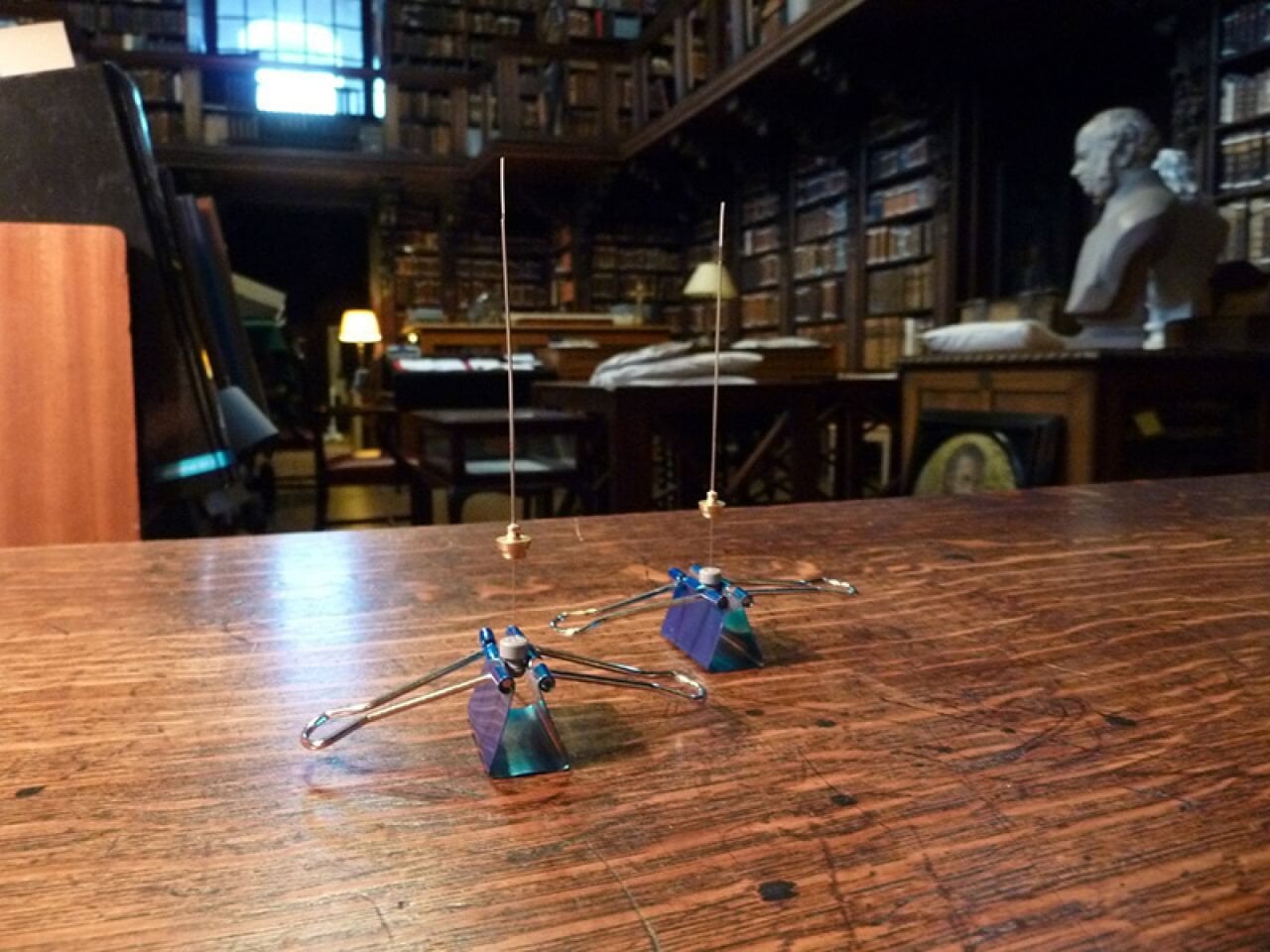

I went on a trip to Japan in 2005 and that’s how I found the love doll that [became the basis for] the series I did in 2010. When I started searching for where my next series was going to go, I looked for inspiration in Japan, because it seems to be an endless source. And I discovered these communities—these Kigurumi communities that do cosplay with costumes and masks. The mask thing really appealed to me; the idea that I could have something that looked like a doll, but could actually move around on its own.

But I’m not an expert on cosplay or Kigurumi. And interestingly, there have been some people on my Instagram that have left nasty comments like, “you have no business in our world.” I understand that—but artists mine other cultures and other images for inspiration. And that is simple.

In your research did you notice any trends that transcended groups? A desire to be seen, or something societal that was overlapping? Did you speak with any of the women who have turned themselves surgically into Barbie dolls?

I tried to reach out to some of the Barbie girls, the people who enhance themselves surgically. But we could never get anyone to respond to us that was willing to let us photograph them. Which is why I started to create my own, by painting the eyelids onto models. But the people that I used in both the Salon show and the upcoming show are fashion models that were willing to have their eyes painted and just sit there. We kind of called it a model nap…

But I thought a lot about it, and the internet invites people to lie about who they are. A lot dress up and take pictures of themselves and post them, but life online is also a great place to pretend and be other things. To live your life as some sort of avatar of yourself. I think this has all been brewing for a while, with things like Second Life, and I understand the appeal of a costume-masked self, although I’ve put on the Kigurumi masks and found them uncomfortable.

The people who wear the masks that model for me, it’s a real variety—male and female. But at the end of the shoot they seem disappointed when they have to unmask. They like being that character and acting out that character.

Do you think that the concept of donning a mask or armor can be traced to aspects of traditional femininity—the idea of putting on another identity, through clothes or makeup that can easily be applied or taken off?

Yes, that is something that I think about all the time, particularly as I age and feel like I need more armor, rather than less, which is counterintuitive to what I would have thought. When I was young, I imagined that you would grow gracefully and naturally into the way you were, and that would be enough—that there would be no resistance to that, which was kind of naïve in a way. I think a lot of women feel that way. And that’s something that I think about daily. Even if you consider eye makeup—it’s what people feel like they have to do just to leave the house, and walk down the street. It’s pretty amazing.

There’s a thin line between acceptable armor, and the full warpaint of cosplay—which is still societally unacceptable.

Is it though? I’m sure there are plenty of cosplayers that can find plenty of people to play with. It seems that just about anybody can find a community they want to be a part of now, if they invest their time in an online community. That’s one of the nice things about the internet—that if you’re into something there’s definitely a whole community of people that will be into it, too.

In some of your past work you create a world of your own making—as you did with the doll houses—and then add the characters in. With this latest work you’re tapping into a world that already exists.

Yeah, I think on a very simple level, I’m finally getting to the point where I can figure out how to play with humans in my work. I have an equal body of work that I would consider failed works. In contrast to my exhibited works, in many of my failed projects I’ve tried to work with humans. I tried to find a way to represent them in a way I was comfortable with. And I guess the Love Doll series got me into a life-size space, and then the cosplayers got me into masking humans and actually having a character that could finally stand on its own. And now, I’m actually speaking with and painting humans, and kind of doll-izing them a bit, finding a way to photograph them that makes them more comfortable to work with.

Is it a huge departure working with people in this capacity?

It’s kind of a relief because in some ways it’s more work, but in a lot of ways it’s less. I know it sounds crazy, but the characters don’t fall over, they don’t need to be propped up. I’m doing all the work. It used to be that I was always tilting the character, moving them around, finding the right angles. With a human I can say, “Look up towards the warm light.” They’re taking direction and looking up at me.

Since you’ve done certain acting projects recently, like guest roles on Girls and a starring role in Tiny Furniture, do you have more sympathy for your subjects?

I’ve only done a tiny part in Girls, and a tiny part on Gossip Girl. But I’ve done lots of TV interviews. I know it’s weird, but it doesn’t feel that different. Somehow, being in front of the camera syncs up with being in back of the camera. Maybe I’ve been so long behind the camera it seems less foreign.

I know there are a lot of photographers that are super-self conscious about having their photographs taken…but it’s funny, I’m really afraid to look bad in a still photo but I’m not afraid to look bad on film or on time-based work. I have two different standards for these types of things.

In film, you get a broader sense of people and how they move and how they talk, but in a photo you just get a static image of “this is how they look.”

And in a still image it can go so terribly wrong! We all feel that way, like “It’s my bad angle, it’s my good angle.”

What do you think of selfie culture? Many cultural critics have said selfies have become popular because subjects get full control over how they’re seen and presented.

I think the desire to turn the camera on oneself has always been there, since Narcissus—the idea that the more we can see ourselves, the more we can understand ourselves. I just don’t think the apparatus was there before, prior to [the internet]. I remember when I first picked up a camera…the first thing I did was turn it on myself. And then I turned it on my family. I feel like, in some really profound way, you look at pictures of yourself and you’re trying to figure out who you are. We walk around every day and we can’t really see ourselves—walking and talking, and ordering our coffee and going out on a date or whatever—and that’s why I think reality TV took off like gangbusters. People have an insatiable appetite for figuring out who they are. So the desire was always there. The selfie culture was something that was out there, but latent. When you throw in camera phones, everybody’s worst and best self just came right out in a crazy way.

It’s not a new trend, technology just made it possible. You know how they called my generation the “Me Generation?” Wouldn’t my generation have done this in the 1970s if they could?

This show is an interesting choice for the Jewish Museum. They’ve just finished a lecture and concert series on marginalized people. Would you consider these marginalized people?

I never really thought of them as marginalized, because they’re essentially people who are having a big party with each other—and it’s not my awareness that they’re being discriminated against. You just go where your party is. Every subculture is marginalized in that they’re not in the center of things, but I mean, you know, are salsa dancers who get together for lessons marginalized? It’s just a group. I don’t really see it that way.

Interestingly, there are two transgender women in the picture, in the group of pictures that you saw, and I’m shooting another transgendered woman on Monday.

Did you specifically ask for trans models?

Yes, I wanted women with different skin colors and different ethnic backgrounds, and the first transgendered woman I shot was Thai. But, I think, in trying to do this work and get across culture representation, I wanted it to be important but also completely insignificant.

Do you think this will inspire another series touching on some of these themes?

I never know. One the hardest things is not knowing where I’ll go next, and not fully understanding where those connections are made. It feels like things in hindsight really leap together, and I really do work in a series of leaps.

I guess it resembles the internet in some ways.

It’s so much like that. That kind of ADD mindset where you just have to find the way to jump from one place to another. That’s why I feel like the internet was invented for me and my brain. And I bet there are millions of people out there who feel the same way. I can go from here to there and back again.

It definitely makes having a normal social life in the 21st century more difficult.

I was asking someone interviewing me the other day about this subject—this really cool guy, very cute—and I asked, “I wonder if I was young, if I’d get involved with internet dating?” And he mentioned he’d met his girlfriend that way, so did many of his friends. He mentioned they’d met on Tinder, and I said, “Isn’t that a hookup app?” Because, I mean, I don’t know anything. But then we started discussing creating a persona online, and trying to pretend who you are, and he mentioned I should try it to see what happens—like what if I was a person looking for love and I found out that the person I found attractive to be a total fake? That would be terrible.

But from a sociological standpoint, it’s interesting to be able to swipe and see how people present themselves.

Well that’s really the conversation. There are an endless number of people to land on, as a representation of yourself. That’s almost the genesis of a series right there.

A coupe on a romantic dateCanva

A coupe on a romantic dateCanva

Robert Duvall with Shirley MacLaine at the 1984 Oscars. Duvall won best actor for his role in Tender Mercies. AP Photo/Reed Saxon

Robert Duvall with Shirley MacLaine at the 1984 Oscars. Duvall won best actor for his role in Tender Mercies. AP Photo/Reed Saxon Robert Duvall, left, as Lt. Col. Kilgore in Apocalypse Now. AP/United Artists

Robert Duvall, left, as Lt. Col. Kilgore in Apocalypse Now. AP/United Artists Duvall at the 2007 Emmy awards, with his trophies for the miniseries Broken Trail.AP Photo/Chris Carlson

Duvall at the 2007 Emmy awards, with his trophies for the miniseries Broken Trail.AP Photo/Chris Carlson

Left: Plastic littered on a beach. Right: Bamboo.Photo credit:

Left: Plastic littered on a beach. Right: Bamboo.Photo credit:  Field of bamboo.Photo credit:

Field of bamboo.Photo credit:  Handing an Earth-painted ball to a child.Photo credit:

Handing an Earth-painted ball to a child.Photo credit:

A woman swims in the oceanCanva

A woman swims in the oceanCanva A happy-looking dolphin popping out of the waterCanva

A happy-looking dolphin popping out of the waterCanva