During one particular late-night editorial meeting, when all of us here at GOOD HQ probably had a few too many, we came up with the idea to send briefs detailing global problems to some of our most creative friends with one simple instruction: to design a solution to the problem in less than 30 minutes, a time frame that would make them think about the problem, but limit the extent to which it might overwhelm them. Call it "The Half-Baked Design Challenge." Some of the solutions are comical. Some are super thoughtful. Some, to be perfectly frank, are mildly disturbing. But all of them engage creatively with a problem in search of a solution, and we think that's a good thing. In this installment, we redesign the Big Mac.

Soon after the American fastfood chain Big Boy Restaurants pioneered a triple-decker burger in the 1960s, Jim Delligatti, owner of one of McDonald’s earliest franchises outside Pittsburgh, took wind of the newfangled creation and—lore has it—Hamburglared his own version in 1967. Within a year, the “Big Mac”—so named by Esther Glickstein Rose, a young advertising secretary who worked at McDonald’s corporate headquarters in Illinois—became so popular that the company added it to menus nationwide.

The Big Mac quickly became the signature item of the rapidly growing chain. Although 500 McDonald’s locations already existed in the United States in 1963, that number had doubled by 1968. Two years later, not only did every state have at least one McDonald’s, but new locations were opening every day around the world, making fast food utterly ubiquitous. Like most foods on the menu, the Big Mac was perfectly engineered, cheap, and, thanks to McDonald’s pioneering assembly-line approach, could be prepared quicker than it takes to say, “Twoallbeefpattiesspecialsaucelettucecheesepicklesonionsonasesameseedbun.”

Some estimate that nearly a billion of the burgers are now sold each year around the world, with about half of those in the United States. (That means 17 Big Macs are consumed every second in the United States). In fact, the Big Mac is so widespread that there’s now a cost-of-living index known as Burgernomics.

Nutritionists see the Big Mac as a gateway drug to the worse health perils of fast food: sugar-filled soda and fat-filled fries, major contributors to the obesity epidemic. On top of that, environmentalists point to the large-scale industrialized farming required to meet increasing demand (and rapidly increasing portion sizes) for red meat as a major contributor to greenhouse gases. According to a recent study out of the University of Michigan, red meat contributes a greater carbon footprint than grains and vegetables combined because it entails deforestation, corn production for food (which requires fertilization, storage, and transportation), water waste, methane emissions, nitrogen excretion, mass slaughter practices (often involving animal transport), and even more transportation to get the meat to its destination. Furthermore, as Michael Pollan and Eric Schlosser have shown, most fast food burgers are supplied by Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, vast feedlots where the corn-fed animals need to be regularly treated with antibiotics and hormones to combat overcrowding and a lack of grass for grazing.

Factory-farmed meat exists to fuel the high demand for global sensations like the Big Mac. So while the burger may have originated as the ultimate symbol of a tasty, efficient meal, the Big Mac has become symbolic of what’s wrong with our food system today.

It’s time to rethink our Big Mac obsession. Let’s use its pervasiveness to create change, bite by perfectly engineered bite. There’s no need to eliminate tasty burgers from the world, nor is that a realistic goal. But we need more than just a better burger. We need a Big Mac that will change the way we think about food and our planet.

Dana Goodyear: Writer, The New Yorker

I have two half-baked ideas. I love the absolute zero pressure that I’m under, like, the crazier the idea is, the better! I divided my 30 minutes into two 15-minute segments, so I have two quarter-baked ideas. One is a radical, philosophical fix and the other is a quick mechanical fix.

The radical philosophical fix would be sort of taking off on this idea which is so current now, even among the chef that you think of as the most meat-centric chef, which is the idea of meat as a condiment.

In this version, you would make a delicious, salami burger-esque patty of mushrooms, beets, edamame, breadcrumbs—all the things that make the best approximation of the tanginess and heft of actual meat. But, instead of it being a vegan Big Mac, you would put ground beef into the special sauce. You would still have the delicious flavor, B12, and manliness of a burger with meat, but you would just be shifting the propor- tions so that the foundation was vegetables and fungi. You could take it a step further and use grass-fed beef as a condiment, but I think that, if we’re in the realm of McDonald’s, the meat has to be relatively cheap. Anyways, this way you’re downsizing the amount of meat without sacrificing the flavor, texture, and the psychological value of having meat present in the dish.

I looked at the nutritional analysis of a Big Mac, and it only has 25 grams of protein. A lot of people will say you need the meat for protein, and I think that you can enhance and up the protein in a patty using a grain like quinoa. Another big argument that people make is that people need cheap calories, and, in fact, a Big Mac only has 550 calories. If you had three Big Macs a day, you would actually be on a very low calorie diet. So I think that this kind of good carb portion of the Big Mac could do well by adding quinoa. It would add protein and calories, as well as make it more nutritious.

I would actually call it the “Good Mac.” It would be tasty, and you would want to remind people that it’s delicious, but then the word “good” suggests food that’s substantial. It’s not fussy or frilly, it sounds good with “mac,” and it also would suggest, without being too heavy-handed, the potential benefits, both personal and environmental.

So that’s the philosophical solution.

The other one, the mechanical chef, has to do with minimizing portion size. What I would do, in this case, is take a Big Mac and turn it into a donut, where you stamp out the middle, and then that punched out, donut hole portion becomes the “Baby Mac,” while the larger donut could be the “Mac Daddy.” Suddenly, you’ve got one product to use as two, and McDonald’s would love the doubled selling power.

Sell the Baby Mac to the kids, and you know they love the whole “gateway drug for kids” things there, and you promote it as the perfect post-soccer practice meal: Dad takes the kids to McDonald’s and orders the Mac Daddy and the Baby Mac—one for father, one for son, a match made in bonding meal heaven. The Mac Daddy, instead of being two 1.6-ounce patties would be two 1.0-ounce patties with the middle taken out, and the Baby Mac would be two 0.6-ounce patties. There would be a shift in the scale, but no shift in the iconic image of the Mac Daddy. And then, there’s the cuteness of the Baby Mac.

You could do one campaign aimed at families, and then another campaign that’s like date night, where you order the Mac Daddy, and then the Baby Mac is for your main squeeze. It brings back the sort of 1950s iconography, too, of two teenagers sitting at a soda bar sharing a milkshake with two straws. Suddenly,that sort of wholesome, date night/family-oriented thing that was part of the original fast food experience is suddenly back in business. You can restore that positive imagery. Yeah, maybe it’s about the donut shape and embracing the decadence of it, so it’s not our idea of an everyday meal; it’s an idea of something special—like a treat.

Ron Finley: Designer and Gardener

We’re not going to get rid of fast food. It’s an institution that’s probably never going to go away. We’re removed from everything, from nature, even though we are nature...What’s wrong with fast food is fast food. My fast food would be akin to the fast food they have in Greece: a cooked meal, prepared from ingredients that come from the area—fresh food. It’s got harvested ingredients; everything includes some version of a tomato salad, and it’s still done fast.

We need to get people back to the soil. We have such disconnection from the planet. Put organic seeds with a little tray in the Happy Meal—that’s the toy.

We need to show children that there’s another way. We can make gardening fun, so they say, “Mom, I planted the seeds and look what happened.” I mean, I put this little, teeny thing in the earth and got this big ass tree. To me, that’s magic. To have a child witness something like that and have them be a part of it, that would be a beautiful thing—to envision change by literally buying a live plant at McDonald’s. Show children how to think, and not what to think. If you get them involved in their food, it’s going to happen.

David Arquette: Actor

This is definitely going to be half-baked. I’d start with the cattle. I’ve always had this idea, I don’t know if it’s at all possible, but to somehow trap the methane gases that the cattle release. You could create some sort of bubble or dome above the animals that traps the gases and takes it and funnels it and makes ethanol, or whatever kind of useful gas you can get from the cattle, and then funnels it back out to use as an energy source. But that doesn’t really change the food part of it.

There’s the whole stretch of the 5 Freeway when you go to San Francisco and it’s just cows—I always think about it when I drive by because you can smell it from miles away. And I’ve just been wondering if there’s a way to channel any of that stench. You could call it “Cowshwitz.” That’s horrible, I know, but it’s a start.

For more fully-baked solutions, check out our companion piece about the future of fast food.

Illustrations by Kate Bingaman-Burt

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

TikTok · Bring Back Doors

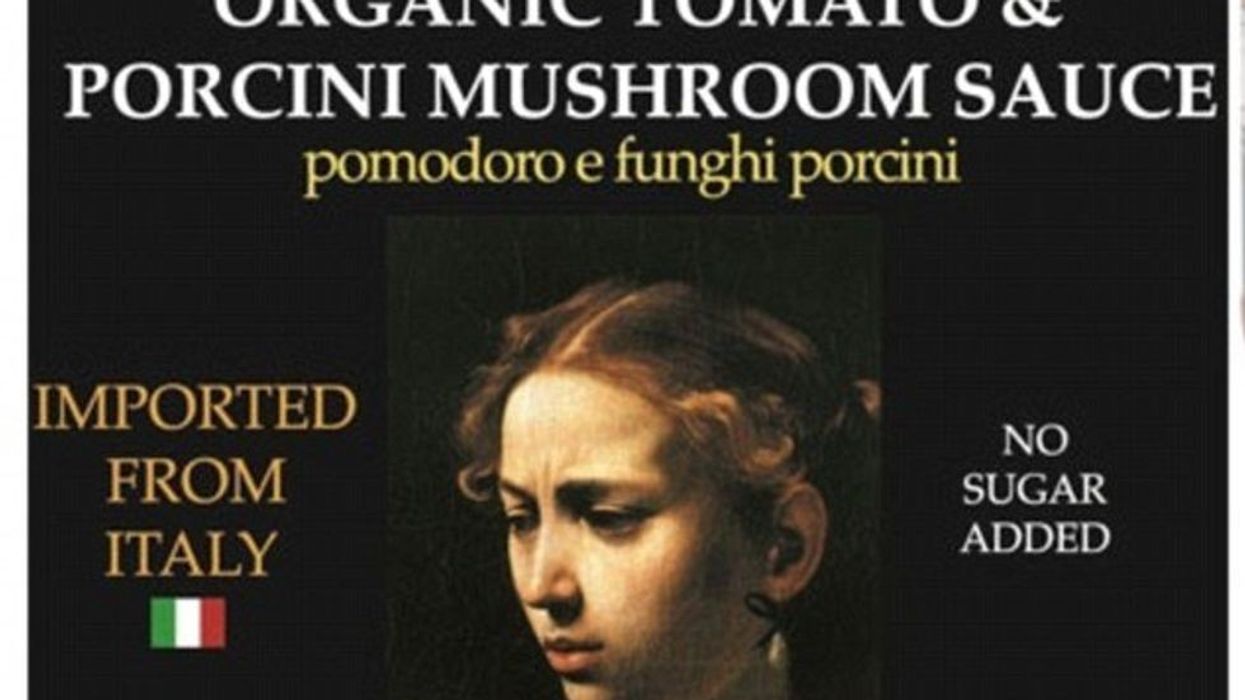

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce

Label for Middle Earth Organics' Organic Tomato & Porcini Mushroom Sauce "Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)

"Judith Beheading Holofernes" by Caravaggio (1599)