Heat stroke is one of the top three causes of sudden death for athletes.

But it’s 100% survivable when it’s recognized and treated right away, according to the University of Connecticut’s Korey Stringer Institute. The organization is named for the Minnesota Vikings player who died from heat stroke in 2001 after being overcome by the heat during training camp.

Time is of the essence when it comes to bringing the athlete’s core temperature down below the danger threshold.

In a consensus statement published earlier in 2018, experts convened by the institute stressed the importance of cooling athletes immediately on site before taking them to a hospital, given that critical damage to cells can occur when body temperature is at or above 104.5 degrees Fahrenheit for longer than 30 minutes.

“This timeframe is what really makes a difference,” says Luke Beval, director of research at the Korey Stringer Institute and lead author of the statement, published in Prehospital Emergency Care. “The sooner you cool someone, the greater their chance of survival.”

Recognizing and treating heat stroke

Being able to provide immediate treatment requires quickly recognizing the symptoms of heat stroke. While central nervous system dysfunction is one of two main criteria, symptoms can be similar to those of other critical health issues common in athletes. For example, dizziness, vomiting, and confusion are also common concussion symptoms.

The consensus statement debunks the misconceptions that athletes with heat stroke will have stopped sweating, have hot skin, or will have lapsed into unconsciousness.

Accurately diagnosing exertional heat stroke requires taking the athlete’s rectal temperature, the authors note. Other methods may not provide an accurate reading of the person’s internal temperature, which can provide a false sense of assurance that the athlete is OK.

Using the principle of “cool first, transport second,” athletic trainers and other on-site first responders should immediately begin cooling the athlete rather than waste critical time waiting for emergency personnel to arrive.

The most effective method is to immerse the stricken athlete in a tub of ice-cold water from the neck down, which cools the maximum body surface area and is more effective than cold wet towels, ice packs, or cold showers. This on-site treatment should continue until the athlete’s body temperature drops to about 101.5 degrees; only then should the athlete be taken to the hospital. Crucially, the consensus statement notes that most hospital emergency departments lack the equipment for full-body cold water immersion.

Practice prevention, but be prepared

In addition to having emergency plans and equipment in place, coaches and trainers should also be prepared to adjust workouts when hot weather is expected. Hot, humid weather heightens the risk of exertional heat stroke, given that it reduces the body’s ability to cool itself by sweating. The most accurate measurement is with a wet bulb globe temperature monitor, which measures temperature, humidity, and other contributing factors.

In an interview with GOOD Sports, Beval stressed the importance of giving athletes time to adapt to the heat. This includes not wearing heavy equipment during the first days of practice, minimizing the number and duration of two-a-day practices, gradually ramping up the intensity level, and allowing adequate rest and recovery time.

“Heat acclimatization is incredibly effective. Of all the extreme environments we can subject our bodies to, like cold or altitude, we have the best ability to adapt to the heat,” says Beval. “Where these practices have been adopted, we’ve seen a drop in deaths.”

Of course, it’s far better to prevent exertional heat stroke in the first place.

On its site, the Korey Stringer Institute notes key preventive measures, including heat acclimatization, wearing appropriate clothing, and avoiding practice during the hottest part of the day. Similar guidelines can be found in the Heat and Athletes section of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention site.

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |  Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva A female artist in her studioCanva

A female artist in her studioCanva A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva

A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva  A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva

A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva  A woman flexes her bicepCanva

A woman flexes her bicepCanva  A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva

A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva  Two women console each otherCanva

Two women console each otherCanva  Two women talking to each otherCanva

Two women talking to each otherCanva  Two people having a lively conversationCanva

Two people having a lively conversationCanva  Two women embrace in a hugCanva

Two women embrace in a hugCanva

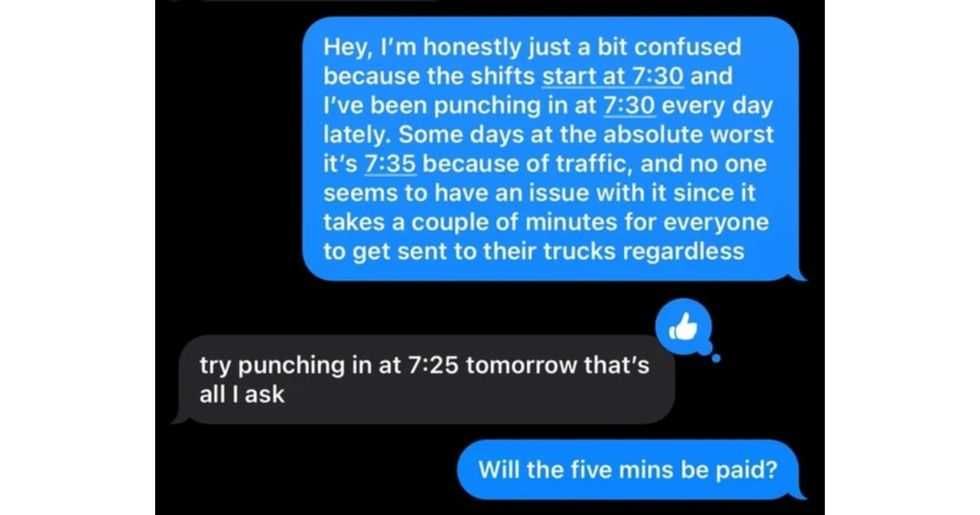

A reddit commentReddit |

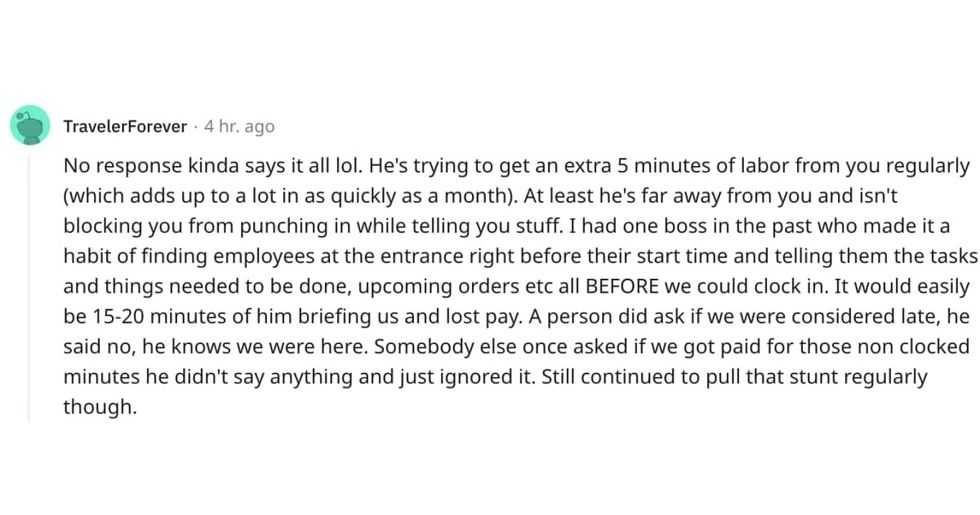

A reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via