In February 2014, comedian and Late Night with Conan O’Brien writer Laurie Kilmartin’s father checked into a hospice with stage IV lung cancer. From his bedside, Kilmartin live-tweeted her dad’s last week of life, producing a stream of morbid, loving, and painfully hilarious jokes that took solace in the absurdities of end-of-life care: the silence, the daytime television, the boring visitors, the experience of seeing your father’s genitals. It made for a tragic and hilarious eulogy.

After her father passed, Kilmartin started working jokes about him and the experience into her standup sets. A few months later she filmed the special “45 Jokes About My Dead Dad,” which the comedy streaming service Seeso is set to release December 29. It wastes no time. The first joke: “Knock, knock. Who’s there? Not my dad.”

The set is every bit as funny and cathartic as the original tweets. Kilmartin roasts cancer, oncologists, funerals, her family, and herself for turning it all into a commercial product. Two years removed from the experience, Kilmartin talked to GOOD about the power of laughing at death and why comedy isn’t courageous.

When did you start writing jokes about your dad’s cancer?

I was talking about his cancer when he had it. I guess that was my little way of hoping that his chemo would work. Some sort of magical thinking that if I talk about it, talk about the worst possible thing happening—him dying—then it wouldn't happen. And that didn't work. Afterwards, you know, I wanted to talk about it in my act just like I talk about being a parent or dating or anything else.

I noticed that when I did any more than two or three jokes, people would start to get restless and it wasn't an easy shift. (When) you're just working a nightclub or a bar, you kind of have to polish jokes a little bit so that people can swallow them down. … I got kinda frustrated with having to bail on the topic pretty quickly. I initially decided, what if I just made a really short special? Part of the gimmick would be it's seven minutes long but it's only cancer jokes.

As I started writing a ton of jokes, I realized it was gonna be way longer than that. I booked a theater and by the time I got to the date, I had about 45 minutes of stuff. Usually it takes me much longer to test material and hone it. It was a pretty quick ramp-up. My dad died in March and we shot it in October. I had the idea to really do a special sometime in July.

During his taped interview in the special, Patton Oswalt calls you courageous. Were you ever thinking about these jokes in terms of courage?

No, I was trying to manage it. It was such a wild and brand new experience. I honestly didn't think he was gonna die until a couple days before he died. I just couldn't process it. It's hard to think ahead. This little thing would happen and I'd try to make it into a joke and then I could put it away, instead of having all these things overwhelm me. It's like, by the end of the day, I turned it into 15 jokes or 15 tweets. You know, what's next tomorrow? It was kind of a way to process it as it was happening, so that I could be in the present for the next day.

The set juxtaposes the somber and the raunchy so well. You have a joke about cremation and masturbation. How did you approach that balance?

The dick jokes were on purpose because I wanted it to be stand-up. That's part of stand-up, being dirty and being stupid. I still wanted to stay in that arena and not have it all be earnest, just to break it up. I think if some people were uncomfortable, a dick joke every seven minutes makes everyone relax a little bit.

What was hard was segueing into it. I had material about being a mother, or being a single mother, all that. That's just sort of normal stuff, whatever. Then it's like, how do I go from talking about masturbating to saying my dad died last month? That was always a challenge. On top of the fact that it was so recent that I wasn't probably as in command of the material as I would be later.

How has your relationship with the material changed over time?

Just the repetition of “My dad died”—the first time you say that, your mouth almost stops. It won't let you finish the sentence. I definitely think the first couple months I was doing it, my voice may have changed. I may have been a little bit quavery. That also probably contributed to audiences not being comfortable with it. But as I got better at saying it and describing it, then it just became another topic I was hitting. It's weird. I do a couple jokes about my dad now in a regular act, and it's no problem. But it's also been a couple years.

When my dad had cancer and I was talking about it, I think the audience almost knew the outcome before I did. I think the audience was like, “You just said your dad has stage IV lung cancer and you're at a nightclub right now? You should probably go home.” Afterwards, obviously everyone knows the outcome, and there's nothing else I can do, so I might as well joke about it.

I think it's definitely easier after someone passes to talk about that situation than as it's happening. Because the audience has some anxiety for you, and when they're worried about you, they're not gonna laugh. They don't want to worry about anything. They just want to laugh. After he died, it just took me a while to get comfortable with it. And then I got used to it. I could utter those words. Once I'm comfortable, the audience is comfortable.

Has this special helped you better prepare for future deaths, or your own death?

I definitely feel more prepared for my own. On a logistical level, with my mother, if she's the next one to go, we did all the getting rid of stuff. She's moved out of the house. So we did all that dehoarding. It's done. All of her stuff is in a closet in my house. That kind of thing is finished. But emotionally, I don't really know. I like to think I'll be a little smarter about it, but my feelings for my mother are so different.

When my dad was dying, it was nonstop love and “Can I help?” My mom isn't dying—she's 79—but it's definitely still a mother-daughter relationship where I feel 14 and like I'm having my emotional boundaries violated. So I actually don't know that I've learned any lessons because I don't act like she's gonna die soon. I definitely treat her in a way where I feel like she's going to live to be 100 and I'll never get her out of my life. She could die tomorrow. I probably haven't learned a thing, sadly.

What’s the funniest thing about death?

I think the funniest thing is the fact that we all know it's coming, and when it comes, we're still shocked. How could that surprise you, that an old person would die? And yet I was like, “This is unbelievable to me.” It was so shocking to be without him and to know that my dad could die too. I think I thought my parents were immune for some reason.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026. Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

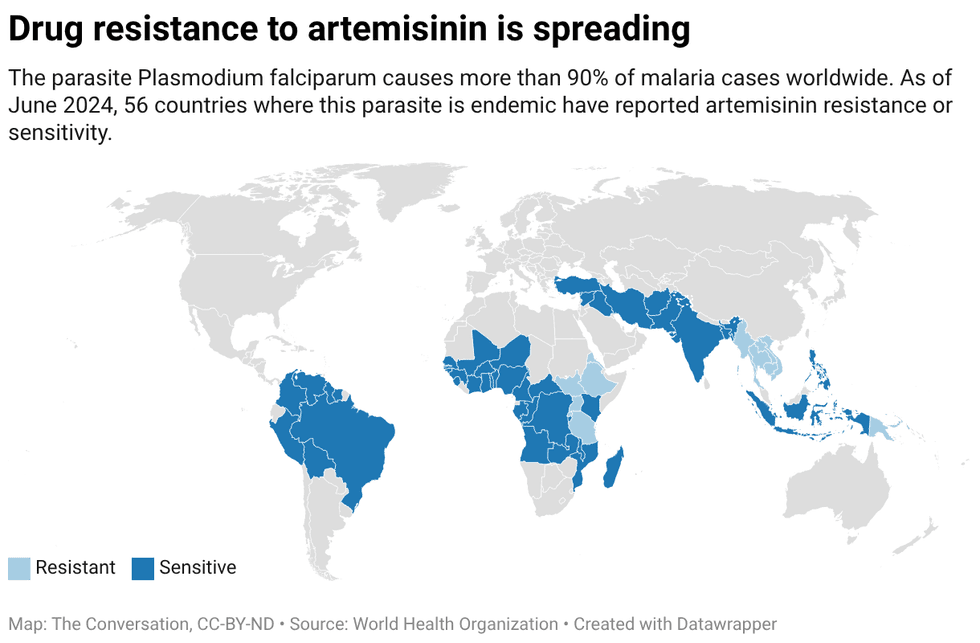

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with