The bright radiance of happiness and the clouds of depression may seem to exist in their own separate stratospheres on the emotional spectrum. But in a new paper published at Molecular Psychiatry, researchers from the University of Oxford and University of Texas at Austin propose that these two different states may actually share the same genetic underpinnings—potentially shutting down the “nature vs. nurture” debate once and for all.

Certain genes make us more “sensitive” to stimuli, leading just as easily to bouts of depression or positivity—suggesting “a complex interplay” between our genes and our environment, says lead researcher Elaine Fox, professor of affective neuroscience at Oxford and author of the book Rainy Brain, Sunny Brain. So trying to blame either our upbringing or our DNA for our mental health is “a bit like asking what is more important for a rectangle—the length or the width,” she says.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Over time, healthier mental habits develop that tip us toward wellbeing and happiness.[/quote]

Fox says that her research with colleague Christopher Beevers reveals that “a specific life event in combination with the development of specific cognitive biases in turn leads to negative habits of mind that tip people more toward depression [or] anxiety.” And the events that steer us either way don’t have to be very dramatic.

Nedalee Thomas, a California entrepreneur, says she experienced “two serious dark depressions” in her late twenties and early thirties, both so intense that it became a struggle to dress herself. One of her depressions was set off by “an unkind remark at Thanksgiving,” while the other was lifted after a shopping trip. “Finding a beautiful maroon velvet coat for a price that I could afford… was like stepping out of the dark into the light,” Thomas says. “It turned me around that simply.”

Fox says that positive biases can be built up in response to specific life events and genetic make-up. “Over time, healthier mental habits develop that tip us toward wellbeing and happiness.”

Zoe Schaeffer, a magazine editor and writer in Pennyslvania, says she is no stranger to “very low lows, but also very intensely beautiful highs, and I don’t mean mania or over-the-top behavior—simply deep and profound joy.” She believes in the genetic underpinnings of her depression, and has tried numerous things for depression over the years, ranging from medication to gratitude practice, to yoga but is keenly aware, as a self-identified “highly sensitive person,” that her environment and situations can help shift her out of depression, as well.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]I’m no stranger to very low lows, but also very intensely beautiful highs, and I don’t mean mania or over-the-top behavior—simply deep and profound joy.[/quote]

Fox says that the current psychometric scale for depression, the Polygenic Risk Score (PRS), is unduly weighted toward the negative, assessing for genes that contribute to one’s risk of becoming depressed, but not for positive emotions. “When studies have looked at how people respond to very positive and supportive environments, we find those with high levels of the very same PRS also have a better response to these positive environments,” she says. Thus, the genes underlying both emotional conditions “are working in a ‘for better and for worse’ manner,” she says.

Fox’s research with Beevers suggests that PRS should be replaced with a “Polygenic Sensitivity Score,” (PSS), “as this better reflects the fact that these genes seem to confer greater sensitivity to the environment.” She believes that if the environment is positive and supportive, those with high sensitivity will be able to “grab the opportunities more easily than those who are less responsive.”

Now that Thomas’s life is more balanced—she’s done raising kids, in a happy marriage, and past menopause, so no longer beleaguered by mood-effecting hormonal fluctuations—she hasn’t found herself back in the trenches of depression like she did when she was younger, though she does experience sadness and down periods, which she says she can manage. Schaeffer finds that she can access her happiness most effectively “when I’m directly present with a physical experience: gardening; cooking; being with animals; using my body in various sports outdoors,” she says.

The ultimate hope for this research, says Fox, “would be to develop highly personalized treatments based on people’s level of genetic sensitivity.” Perhaps in the future, if you turn up low on the PSS scoring system, you’ll be a candidate for the kind of cognitive training that would help you tune in better to your environment for your own emotional benefit, no matter what your genetic code says.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

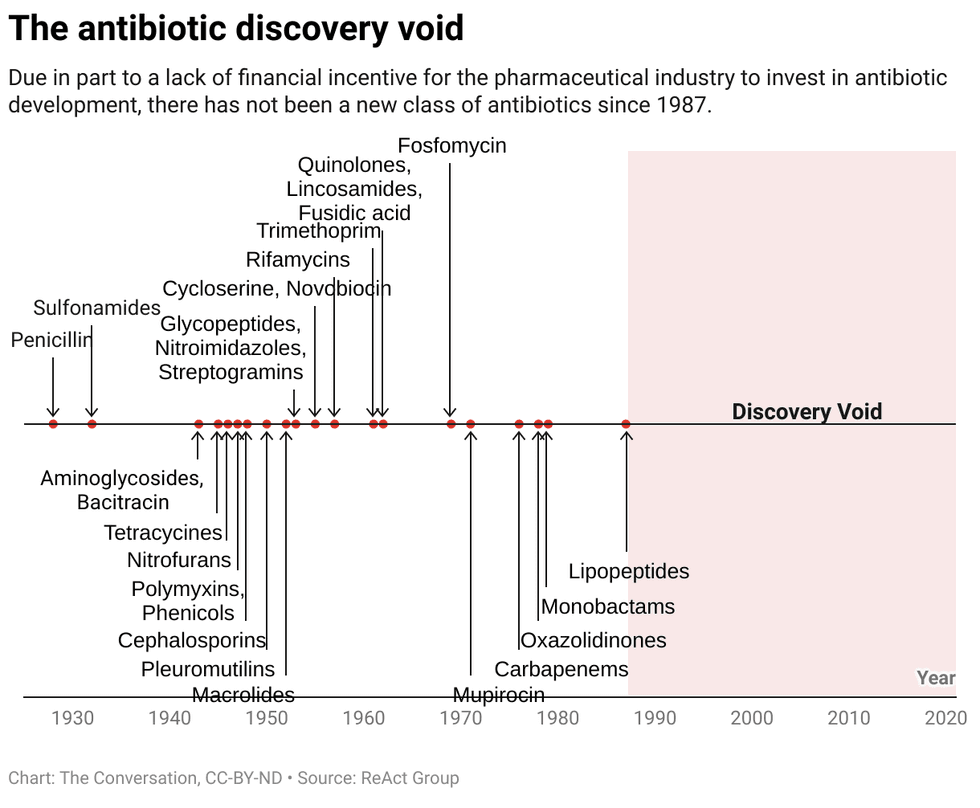

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:  Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:

Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:  Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit:

Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit: