I have a theory that every person is constantly pulled—almost by some invisible magnetic force—to one particular place that feels safe and magical and misty with nostalgia. Maybe it’s the gazebo where you got married or the garage where you started your first band. It feels like, if you just get back there, the white noise will gently dim and life will briefly make sense again.

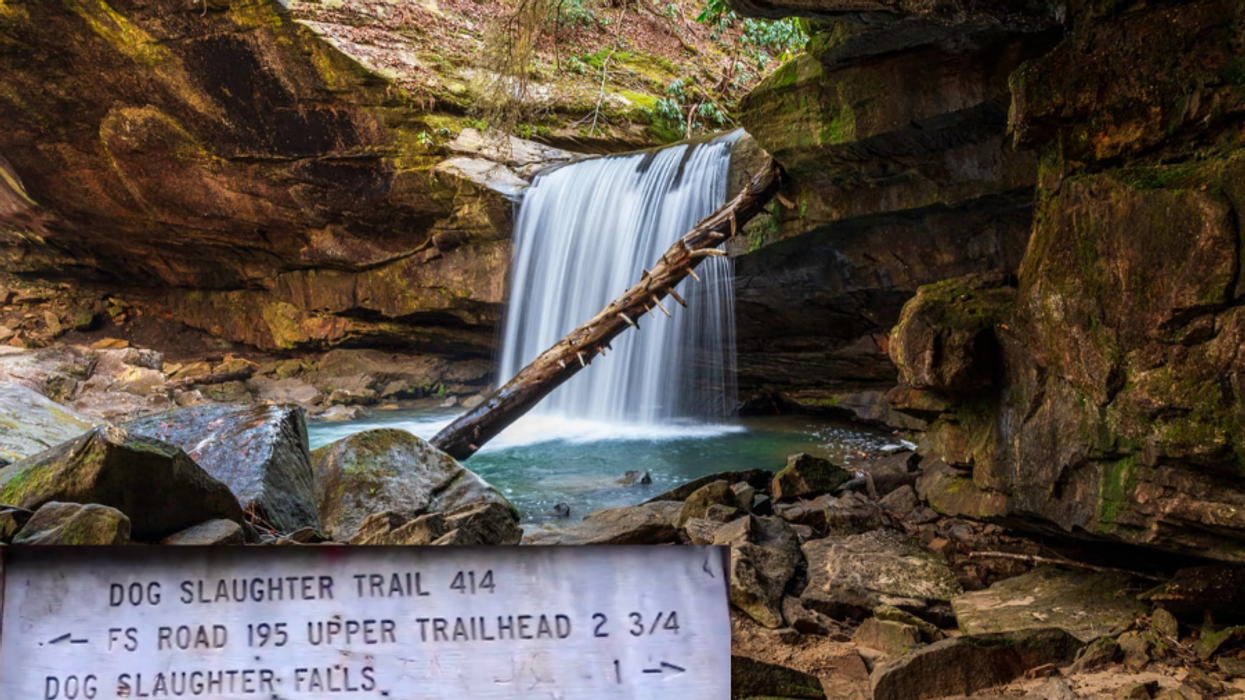

For me, that place is the flat part of a nondescript boulder positioned opposite a 15-foot waterfall with a very disturbing name.

I first visited Dog Slaughter Falls as a middle-schooler, and I was adamantly not stoked about the idea. At that time, I was a shy, somewhat artsy kid searching for meaning in the conservative Bible Belt town of Williamsburg, Kentucky. I was still a lump of unformed human clay—largely consumed by rock music and entirely disinterested in matters relating to the shoebox church my parents drug me to each Sunday. But I was also a Certified Strait-Laced Good Boy, so I entertained my mom’s pitch: an afternoon of hiking with a group of older folks, guided by the botanical knowledge of a nature-loving priest.

Turns out this was more of a demand than an invitation, so I invited my friend Tyler along for this frolic from hell—at least I could suffer alongside a kindred spirit. I wasn’t expecting to enjoy this foolishness, let alone have it alter my brain chemistry in a real, profound way. But life is strange.

Dog Slaughter Falls is located within Daniel Boone National Forest, which sprawls across 708,000 acres and 21 counties in Eastern Kentucky. But even if you’re not from the area, you still might be familiar with its star attraction: the massive and majestic Cumberland Falls, one of the only places on Earth where you can regularly see a "lunar rainbow"—a phenomenon created by moonlight rather than sunlight.

Visiting the so-called "Niagara of the South" was a staple of my formative years. Outside of buying scratch-off tickets and meandering around Wal Mart, there really wasn’t much to do in Williamsburg, so we frequently made the 20- or 30-minute trip up to Corbin, windows rolled down, cranking whatever new indie-rock album we were obsessed with. I vividly remember road-testing Modest Mouse’s Good News for People Who Love Bad News as we navigated those windy roads late at night, my senses heightened by the darkness and perpetual motion. One time, my friend Calep showed up with a burned copy of Brand New’s The Devil and God Are Raging Inside Me—hearing "Jesus Christ" in that setting felt legitimately cinematic. During that era, my friend Rishi and I, having borrowed an unwieldy camcorder from a classmate, trekked down to the Falls' beach area and, utilizing a form of forced perspective, staged a tragic suicide scene from our (still-unfinished) amateur film It’s Great to Be in Cincinnati.

I’ve always felt a restorative force at Cumberland Falls, and I know a lot of people who feel similarly. Also, as a restless kid with big-city dreams, I felt trapped in my hometown, but living near the Falls was a badge of honor—something I could name-drop to a stranger in conversation and feel vaguely proud. But…it was also a state park swarmed with tourists—it belonged to everyone. Dog Slaughter, on the other hand, felt like a secret.

- YouTubewww.youtube.com

Let’s talk about the name—or, more specifically, how little we know about it. According to Kentucky State Parks, the origin of the grisly "Dog Slaughter" moniker "remains a mystery," despite regular questions from visitors. The Independent Herald, a newspaper located in nearby Oneida, Tennessee, has a couple theories: One, which I also heard as a kid, is that "unwanted pets were once killed there." Yeah, pretty horrifying! Another: "that hunting dogs were once slain by a beast unknown at this site—maybe a wolf, maybe a bear … some even say Bigfoot." (This also calls to mind the local legend: the Mulberry Black Thing, but we’ll save that one for another day.)

I reached out to some local experts, thinking maybe, just maybe, they knew a deeper truth obscured from the general public. The responses varied.

Jehan Abuzour, parks program services supervisor (previously park naturalist) at Cumberland Falls State Resort Park since September 2023, is aware of two stories. (Dog Slaughter is technically not located on park property, though there is a connecting trail.) "I’ve heard that [frontiersman] Daniel Boone wrote in his journal about how he brought his hunting dogs with him in the area and they chased a raccoon, and the raccoon went under the lip of the Dog Slaughter Falls waterfall," she says. "The hunting dogs didn’t see the cliff, and they went over it and died. Daniel Boone supposedly named it Dog Slaughter Falls. The other story is pretty broad: Basically there was a group of early settlers of Kentucky, and they encountered a pack of wild dogs out there at the falls.“

Pamela Gibson, former trails maintenance supervisor and volunteer coordinator at Cumberland Falls State Park, calls Dog Slaughter a “local landmark”—but with a name that invites a lot of complaints. "According to what the Park had written, Dog Slaughter Falls was named for an incident that happened before the area was very populated,” she says. “Story goes, the locals were out hunting [raccoons] in the area using dogs. The dogs had the coons pinned in the creek, when the raccoon got one of the dogs in the water, drowning several dogs. Everyone knows dogs do not stand a chance with a raccoon in the water.”

Connie Howard has been hiking there for over four decades and lives in a cabin near the trailhead. (Speaking of which, she’s had “many hikers who have gotten lost knock on [her] door during the night.”) But she doesn’t think “anyone is sure” how Dog Slaughter got its name. “The old timers, long deceased, told me it was because of hunting dogs being killed by a mysterious beast that lived in the area,” she says. “Who knows?”

The whole "slaughter" branding may intimidate some people from venturing out there—notably, on the horror front, it even inspired a Creepypasta involving a camping trip, a little girl’s diary, and a mysterious creature. But the hike, at least in my travels, has been the opposite of unsettling. Then again, I’ve always been out there with at least one other person—or, in the case of my first time, with a large group of people I mostly wanted to avoid.

Tyler and I jostled in my family’s minivan as it slowly rumbled roughly three miles down a gravel road. I remember Shania Twain’s country-pop hit "Man! I Feel Like a Woman" playing on the radio, its signal shifting more to static with each bump—it felt like an omen, but I wasn’t sure what kind. We arrived at an unmarked pull-off area overseen by a huge rock, and all of the churchgoers piled out of their cars and onto the trail, with Tyler and I shuffling to the rear. Sensing our awkwardness, a rowdy (and, frankly, somewhat frightening) 50-something man we’ll call Jerry decided to become our unofficial tour guide.

As the rest of the hikers moseyed along the shady, ultra-green, 2.5-mile path, stopping periodically to gaze at flowers, our out-of-nowhere buddy countered that peacefulness with lots of antics. Multiple times, he shouted caveman gibberish with a cavernous roar; at one point, he frantically jumped on a downed tree that crossed along Dog Slaughter Creek, almost daring it not to break; and, in what remains the funniest thing I’ve ever seen, he tripped over a rock, his body soaring a Superman-like free-fall before smoothly skidding into fresh mud. He arose, wiped his eyes, and shouted manically. Jerry was having himself a day.

Meanwhile, I was falling in love—even if I was embarrassed to admit it at the time. Despite the chaos, I felt serene among the fizzy creek sounds and creeping moss and cold rocks. During a picnic lunch, we all gathered on that massive boulder, a short swim away from the base of the falls, and I was hypnotized by the unending rush of water. "This is always just…out here," I thought. And I’ve dusted off that disbelief every time I’ve returned over the following two-plus decades, often joined by my wife (Jen) and our Brittany Spaniels (Tegan and the late Gabriel).

I’m an anxious, depressive person by nature—I have trouble slowing down, living in the now, savoring the good moments before they slip through my fingers. But I crave the zen-like tranquility I feel at Dog Slaughter. I always leave feeling blissfully still—as if I’ve stopped the flood, even momentarily, to gaze at one outside myself.

Left: Plastic littered on a beach. Right: Bamboo.Photo credit:

Left: Plastic littered on a beach. Right: Bamboo.Photo credit:  Field of bamboo.Photo credit:

Field of bamboo.Photo credit:  Handing an Earth-painted ball to a child.Photo credit:

Handing an Earth-painted ball to a child.Photo credit:

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit

A parking lot for charging electric vehicles.Photo credit  Oil production.Photo credit

Oil production.Photo credit  Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit

Sun shines over the Earth.Photo credit

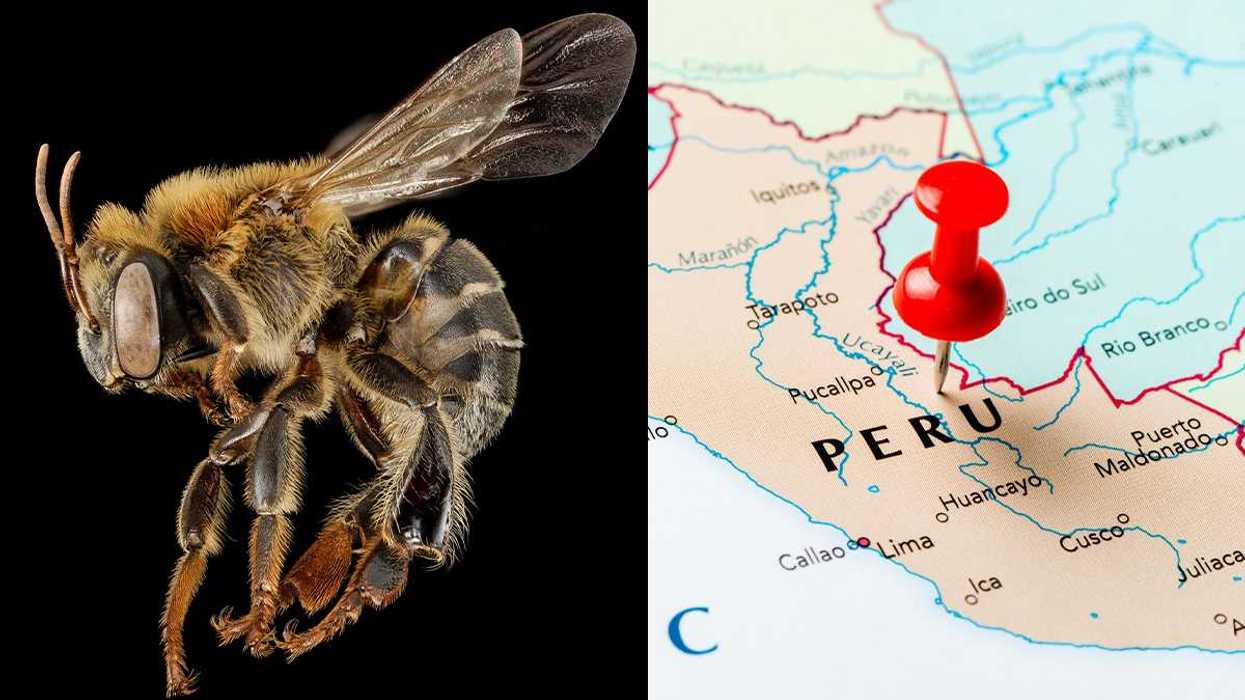

Peru stingless bee.USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab/

Peru stingless bee.USGS Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab/  Indigenous Peruvian people.Photo credit

Indigenous Peruvian people.Photo credit

Representative Image: Accents reveal heritage and history.

Representative Image: Accents reveal heritage and history.  Representative Image: Even unseen you can learn a lot from an accent.

Representative Image: Even unseen you can learn a lot from an accent.

Rice grain and white rice.Image via

Rice grain and white rice.Image via  Person eats rice.Image via

Person eats rice.Image via  Washing and rinsing rice.

Washing and rinsing rice.  Mother and daughter eating rice meal.Image via

Mother and daughter eating rice meal.Image via

President Donald J. Trump and photo of a forest.

Public united and adamantly opposes Trump’s plan to roll back the Roadless Rule

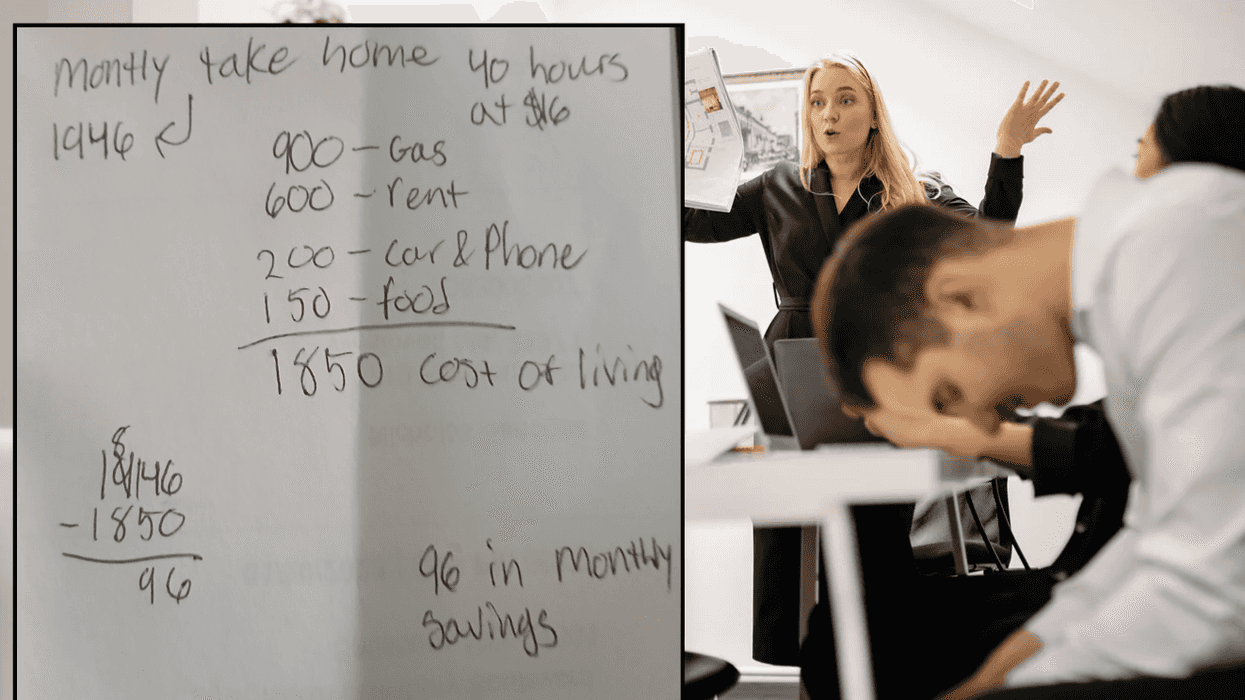

There doesn't seem to be much agreement happening in the U.S. right now. Differing moral belief systems, economic disparity, and political divide have made a country with so many positives sometimes feel a little lost. Everyone desperately seeks a niche, a connection, or a strong sense of community to which they can feel a "part of," rather than just "apart."

But there seems to be one thing that the country strongly unites over, and that's the "Roadless Rule." With the Trump Administration attempting to roll back conservation policies that protect U.S. National Forests, Americans are saying in harmony an emphatic "No." A nonpartisan conservation and advocacy organization, the Center for Western Priorities, reviewed a comment analysis on the subject. After receiving 223,862 submissions, a staggering 99 percent are opposed to the president's plan of repeal.

What is the 'Roadless Rule' policy implemented in 2001?

The Roadless Rule has a direct impact on nearly 60 million acres of national forests and grasslands. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the rule prohibits road construction and timber harvests. Enacted in 2001, it is a conservation rule that protects some of the least developed portions of our forests. It's considered to be one of the most important conservation wins in U.S. history.

America's national forests and grasslands are diverse ecosystems, timeless landscapes, and living treasures. They sustain the country with clean water and the wood products necessary to build our communities. The National Parks protected under their umbrella offer incredible recreational retreats and outdoor adventure.

Why does the administration want to roll it back?

U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins told the Department of Agriculture in a 2025 press release, “We are one step closer to common sense management of our national forest lands. Today marks a critical step forward in President Trump’s commitment to restoring local decision-making to federal land managers to empower them to do what’s necessary to protect America’s forests and communities from devastating destruction from fires." Rollins continued, “This administration is dedicated to removing burdensome, outdated, one-size-fits-all regulations that not only put people and livelihoods at risk but also stifle economic growth in rural America. It is vital that we properly manage our federal lands to create healthy, resilient, and productive forests for generations to come. We look forward to hearing directly from the people and communities we serve as we work together to implement productive and commonsense policy for forest land management.”

Forest Service Chief Tom Schultz explained the Roadless Rule frustrated land management and acts as a challenging barrier to action. It prohibits road construction needed to navigate wildfire suppression and properly maintain the forest. Schultz said, “The forests we know today are not the same as the forests of 2001. They are dangerously overstocked and increasingly threatened by drought, mortality, insect-borne disease, and wildfire. It’s time to return land management decisions where they belong – with local Forest Service experts who best understand their forests and communities."

Why are people adamantly opposed to the proposed rollback?

A 2025 article in Earthjustice, a nonprofit environmental law organization, expressed its concern over the protection of national forests covering 36 states and Puerto Rico. A rescinded rule allows increased logging, extractive development, and oil and gas drilling in previously undisturbed backcountry. Here is what some community leaders had to say about it:

President Gloria Burns, Ketchikan Indian Community, said, "You cannot separate us from the land. We depend on Congress to update the outdated and predatory, antiquated laws that allow other countries and outside sources to extract our resource wealth. This is an attack on Tribes and our people who depend on the land to eat. The federal government must act and provide us the safeguards we need or leave our home roadless. We are not willing to risk the destruction of our homelands when no effort has been made to ensure our future is the one our ancestors envisioned for us. Without our lungs (the Tongass) we cannot breathe life into our future generations.”

Linda Behnken, executive director of the Alaska Longline Fishermen’s Association, stated, "Roadbuilding damaged salmon streams in the past — with 240 miles of salmon habitat still blocked by failed road culverts. The Roadless Rule protects our fishing economy and more than 10,000 jobs provided by commercial fishing in Southeast Alaska.”

The Sierra Club's Forest Campaign Manager Alex Craven seemed quite upset, saying, "The Forest Service followed sound science, economic common sense, and overwhelming public support when they adopted such an important and visionary policy more than 20 years ago. Donald Trump is making it crystal clear he is willing to pollute our clean air and drinking water, destroy prized habitat for species, and even increase the risk of devastating wildfires, if it means padding the bottom lines of timber and mining companies.”

The 2025 recession proposal would apply to nearly 45 million acres of the national forests. With so many people writing in opposition to the consensus, the public has determined they don't want it to happen.

Tongass National Forest is at the center of the Trump administration's intention to roll back the 2001 Roadless Rule. You can watch an Alaska Nature Documentary about the wild salmon of Tongass National Forrest here:

- YouTube www.youtube.com

The simple truth is we elect our public officials to make decisions. The hope is they do this for all of our well-being, although often it seems they do not. Even though we don't have much power to control what government officials do, voicing our opinions strongly enough often forces them to alter their present course of action. With a unanimous public voice saying, "No!" maybe this time they will course correct as the public wishes.