The last time you talked about sweet potatoes, we’re guessing the conversation went something like, “Sweet potato fries are the bomb dot com!” or maybe, just maybe, while sitting around a dinner table surrounded by friends you asked the philosophical question, “Hey guys, what’s the difference between a sweet potato and a yam?”

But what if we told you sweet potatoes just might be a godsend for millions of malnourished global citizens?

In June, four scientists with a sweet potato specialty (what a life) won the World Food Prize. Their work has been simple but profound—boosting the amount of Vitamin A and other nutrients in this easily cultivated staple crop, thus combating malnourishment in developing nations.

Vitamin A in particular has been a touchpoint for millions of impoverished individuals around the world. Research has shown that giving a Vitamin A capsule every six months to malnourished children could reduce their death rates by 25 percent.

One highly controversial solution is the genetically modified organism (GMO) Golden Rice, jacked up with loads of Vitamin A. Proponents of this crop frame it as the poster child for why GMOs are a boon to humanity. Opponents say that we should rely on organic ways of delivering Vitamin A, a naturally occurring element in some vegetables.

Enter the humble sweet potato.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]By 2030, we hope to reach a billion people with these bio-fortified crops.[/quote]

Maria Andrade of Cape Verde, Robert Mwanga of Uganda, and American Jan Low, all of whom work at the renowned International Potato Center in Peru, and Howarth (his nickname is “Howdy”!) Bouis of the D.C.-based HarvestPlus, have all spent many years researching sweet potato biofortification. According to Dan Charles of NPR, who trailed Andrade back in 2012, sweet potatoes are rich in beta-carotene, the nutrient which gives its distinct orange hue (see also: carrots). But the sweet potatoes in impoverished countries like Uganda and Mozambique have yellow or white flesh—their nutritional value is much lower. So the researchers took varieties of sweet potato that are much closer to what we eat here in the U.S., then figured out which ones would grow best in African soil. From 2007 to 2009 they distributed samples of these tubers to 24,000 farming households—the results were astoundingly positive.

But just because the team has been recognized on a global level doesn’t mean it has any plans of slowing down. In fact, the group says it aims to reach 10 million households by 2020. HarvestPlus founder Howarth Bouis adds, “By 2030, we hope to reach a billion people with these bio-fortified crops.”

It should be noted that biofortification can involve genetic modification; however, these sweet potato researchers used conventional breeding methods. It should also be noted that past winners of the World Food Prize have been GMO researchers—it’s not a deal breaker. Thankfully the sweet potato research evades all GMO controversy. And part of the researchers’ work is straight-up evangelism, convincing farmers to replace pale sweet potato varieties with their vividly hued cousins.

"We are still doing this: theater in villages, singing about orange flesh sweet potato, how good it is, how you feed it to your children, and showing recipes so that they get used to it," Andrade told Charles. One only hopes that sweet potato fries are included in the recipe book.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit:

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

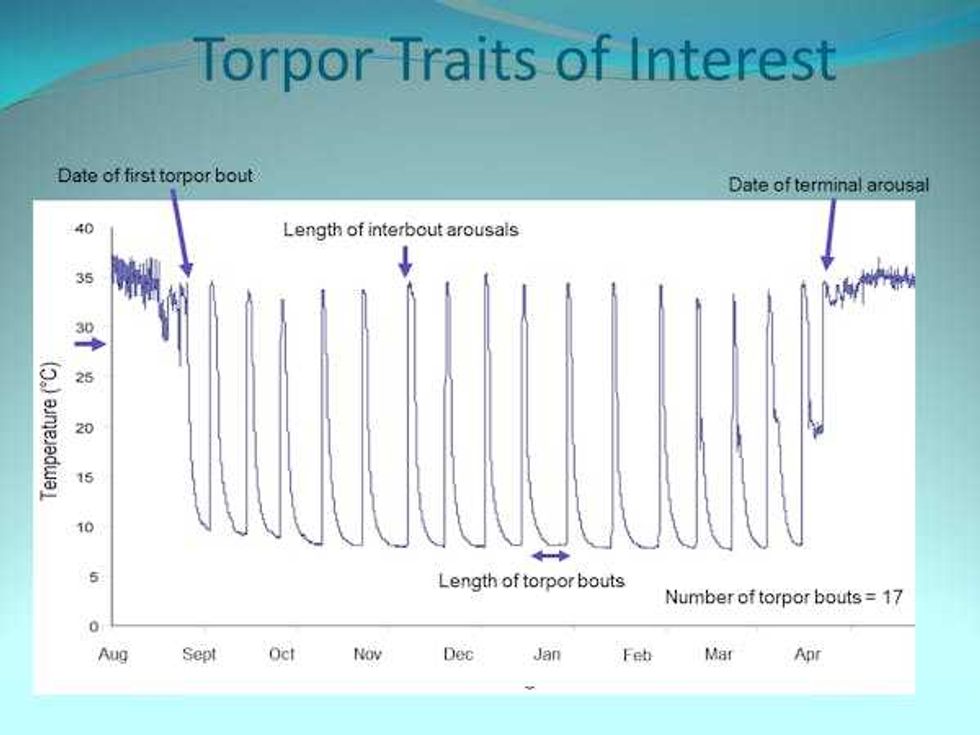

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided