I was offered my first full-time position straight out of college. It was everything my family and I had hoped it would be: I would get insurance, benefits, a retirement fund, branded clothing for my parents to show off. I expected my parents to be happy because this job proved I could succeed at doing what I loved. Instead, our relationship deteriorated to the point where we stopped speaking—and I hastily moved out into my own apartment.

Four years before I got the job, when I was just entering college, my parents and I were standing in the living room, yelling at each other about my coming out. My Taiwanese mother hadn’t taken it well and tried to disown me on the spot, making me swear I’d never tell my 80-something grandmother. But my Irish-Italian father refused to kick me out.

This time around, my mother asked me to stay; my father told me to get out.

I didn’t understand why he was so mad at me or what I did to destroy our relationship until one visit home years later, when my dad eventually confessed he’d been upset with me for not contributing more to the family once I’d gotten that job. He pointed out I never contributed to the grocery budget and never gave money to share the electricity bill. Then, during a TV commercial break, he explained that I made more out of college than my parents had their entire lives.

That was the first time we had ever spoken about salary—or money in general. My parents never gave me an allowance. They didn’t pay my college tuition. They never taught me about investing or savings accounts. The closest I ever got to a bank growing up was in a car parked outside, where they told me to wait while they ran in and did “bank stuff.” Everything I knew about money I figured out through research and my own mistakes. So, it never occurred to me to share my newfound income with my parents.

I was mortified more than shocked when my dad called me out: As a 21-year-old college grad and first-generation immigrant, I never knew there was a duty to contribute to anything other than my own student debt. I had expected to take care of my Taiwanese mother eventually because that was what she had done with my grandmother. That much cultural responsibility, I knew. But everything I learned about American culture taught me to “follow my dreams”—to make money for me and my future, doing what I loved. Future-forward: my own personal manifest destiny.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]The sudden class discrepancy between me and my parents was bizarre and not something any of us were prepared for, it turns out.[/quote]

When I showed my parents my retirement information packet, I now realized why they gave me such an odd stare of disbelief—my parents, both immigrants, who had always worked from home doing odd jobs for our neighbors under the table, who lived on disability, had never had one themselves. Long ago, before they ever had me, they retired from their careers in fashion and music; neither path had provided them stability or residual income after they left. We lived paycheck to paycheck on disability, Medicaid, and money from errands my dad did around the neighborhood for our elderly family friends.

We never starved, but we did eat canned chili and TV dinners more than anything else because it was all we could afford. I used to steal cafeteria lunches—I was too afraid to sign up for school lunch out of the stigma that surrounded the daily ritual of going up for it in front of everybody who bought their own. When that got me in trouble, I wouldn’t have lunch unless my friends packed me one themselves. I remember crying when one of my best friends packed me a traditional Japanese bento; I’d never had something so carefully made for me to eat. But I still didn’t realize how poor we were until my parents pointed it out years later. The sudden class discrepancy between me and my parents was bizarre and not something any of us were prepared for.

My parents shielded me from a lot of the shame that comes from being poor by not complaining about the difficulties, but by doing so, I didn’t realize the difficulties until they were pointed out. Because as long as I was excelling at my academics and becoming successful—better off, in their minds—the struggles to make my situation happen didn’t need to be talked about. The past lives my parents lived took second priority to the person I had an opportunity to become.

Immigrants come to the U.S. to live the “American Dream”—to be successful, to be independent, to live a life that had everything the life they left behind did not. But when they have kids, like me, their dreams take on a life of their own, away from the context they themselves grew up with. We’re not only fighting for our own modern pursuits, we’re also supposed to understand a world we never knew ourselves. The pressure has multitudes: Be successful and be your own person, but remember where you come from even if it’s not what you most intimately know. What I’ve come to realize is that being an adult American citizen and a good daughter of an immigrant can often be at odds.

To call navigating the shifting responsibilities and burdens between first- and second-generation families—what honor means and what wealth can do and for who—“hard” is an understatement. So many things go unsaid until some miscommunication occurs, as it did in my case.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]I was raised in a different world from the one my parents grew up in.[/quote]

I’m not the only immigrant that learned the hard way. When my friend, Mark, a second-generation Filipino immigrant, graduated from college, his mom asked him why he wasn’t sending his younger sister money.

“My sister is only a few years younger than me, and I was freshly out of college,” he explains. “I never remotely assumed I had that responsibility.” There’s this missing context around our responsibilities as immigrant children that gets lost between our generations, perhaps in the move to America. We’ve often never met our relatives back in the “homeland,” or have seen them only once or twice, so our connections feel weaker and perhaps less urgent to maintain. But “closeness” doesn’t make a difference in other cultures: Your extended family is still your kin, and what you can provide for your forebears illuminates how much you recognize their love and labor.

Mark eventually realized his parents had been sending money back to his family in the Philippines for years. “They spent their entire lives taking care of everyone, so it’s implicit to them,” Mark continues. “But for me, I grew up in a different reality.”

The same is true for me: I was raised in a different world from the one my parents grew up in. I never asked about their childhood because to me, they weren’t people with history, they were simply my parents. When I finally did inquire, I learned that the reason they were so critical of my pursuits was because they too had worked in fashion. They feared I would be exploited as they once were.

Even if you aren’t financially supporting your family, children of immigrants are still expected to take their parents’ career expectations to heart. “You can be anything, as long as it’s in the STEM field” was the common mantra my friends and I would complain about. We are encouraged to be doctors, lawyers, nurses, engineers—anything with a stable, high salary and benefits. Our parents wanted for us what they sometimes couldn’t achieve themselves. But the consequence is usually conflict or outright revolt. Cousins are pitted against cousins in a competition for who is the most obedient. My mother even lied to me about my cousins’ careers as a way to convince me not to pursue art: “Your cousin is in medical school; why aren’t you?” It wasn’t until years later that I realized we’d all mostly pursued creative fields.

If we can achieve any recognizable marker of success that takes a burden off our families, it makes our relationships with our parents easier. Mark went to school on scholarship, which afforded him the opportunity to use college to explore what he wanted rather than what he thought he owed his parents (who wanted him to be a doctor).

But when Mark told his parents about his work helping immigrant communities in New York, they were not thrilled. To them, a job like that was a rebellion against everything they had struggled so much to build for Mark. “I eventually realized the narrative of working hard for success doesn’t just come out from a place of ‘honoring your family,’ but also legitimate fear about making waves, fear about having to make trouble,” he told me. “When you grow up as an immigrant kid, you’re not supposed to disturb the peace; you’re not supposed to fight for what you believe in because they already did. Our parents made their way, so we shouldn't have to struggle.”

As immigrant children, we struggle to find the “right” version of success. Mark was making enough money and contributing to his family, but his own aspirations were different from those of his parents. The relationships between money and success and jobs are both delicate and nuanced for our immigrant families, so we wrestle to find work that honors our families and pushes us forward but doesn’t discount the history of what got us here.

One of my friends has stayed in a job she hates for years because it offered her the ability to financially provide for her mother, who is an undocumented nurse from the Caribbean. Another friend sends a portion of every paycheck she makes as a freelancer to her cousins at the request of her mother, who does the same with her meager caretaking salary. When I’ve asked what compels her to do this, the answer has always been, “It’s what we have to do.”

My other friend, a brand manager for a PR firm, is saving her money not only to pay off her student debt but to help with her mother’s retirement (she and her sister want to buy her a house). She’s even trying to convince her mom to make a Pinterest board of her dream home so that she knows what she has to “manifest.”

All of us immigrant children approach our debts—financial and cultural—with anxiety and love intertwined. We recognize that success and independence mean different things in different cultural contexts, and as children of diaspora, we’re often trying to fulfill more than one definition of what those words mean. Sometimes how we fulfill one definition contradicts another approach, but neither answer is truly wrong. How each of us chooses to repay our parents’ debt as migrants is different, but it’s a conversation—and financial decision—that we all grapple with every day of our lives.

The other week, I went home to bring my mother flowers and take her to the spa. I spent the day explaining what each product did, how it was part of my research for new stories, and asked her for her input to include her in my work process. When I was a child, she refused to buy me beauty products, but now we talk about them all the time. It’s not that she is thrilled I have become the person I am with the job that I do. I don’t make as much money as they’d be happy with. But we love each other and are guided by what we hope we can do for each other. We talk about money more now—my parents and I pester each other to ask if the other needs an errand done, a bill paid, or help paying for something. None of us ever admit to needing help, but we’re all proud to be able to ask the question, relieved we could help if ever truly asked. We don’t hide our curiosity because now we know the shame of being fearful doesn’t help; communication about it does. The root of it is our love, after all. We are afraid for each other. It’s a guilt we don’t want to let go of, a weight we don’t want to put down.

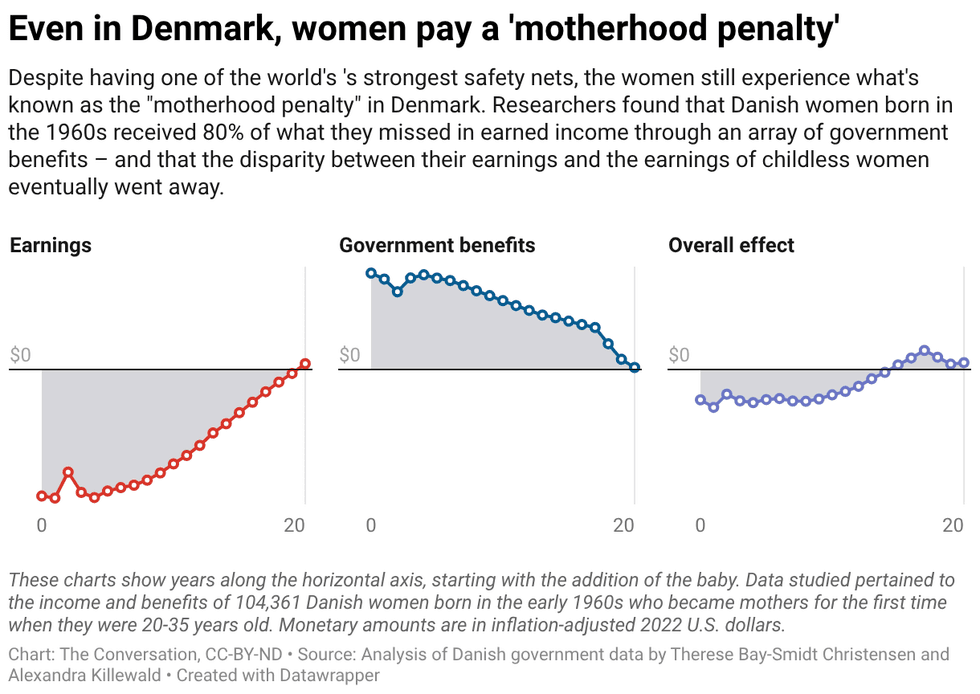

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents. Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.