A popular rule of thumb among proponents of healthy food is that the fewer ingredients there are in something, better it is for you. With a remarkable 37 or so ingredients, many of which are polysyllabic chemical compounds, Twinkies would seem to embody the antithesis of that rule.

The photographer Dwight Eschliman was never a health nut himself, but he was raised by one; his mom kept her kids away from meat, dairy, or any kind of processed food. When Eschilman went away to college, he loosened up a bit, allowing himself to indulge in all sorts of previously forbidden treats, but by the time he had kids of his own, he found a renewed appreciation for simple, healthy food—and a renewed skepticism of chemical-filled, preservative-laden snacks. He'd also developed a love of disassembling ojects and photographing their component parts.

"Thus, this project," he writes in his photography book 37 or so Ingredients. "It's the product of a kid that was raised to be suspicious of foods that weren't assembled in mom's kitchen, and bordering on obsessive compulsive."

What follows is a selection from Dwight Eschliman's 37 or so Ingredients. For more information or to order a copy of the book, email twinkiebook[at]eschlimanphoto[dot]com.

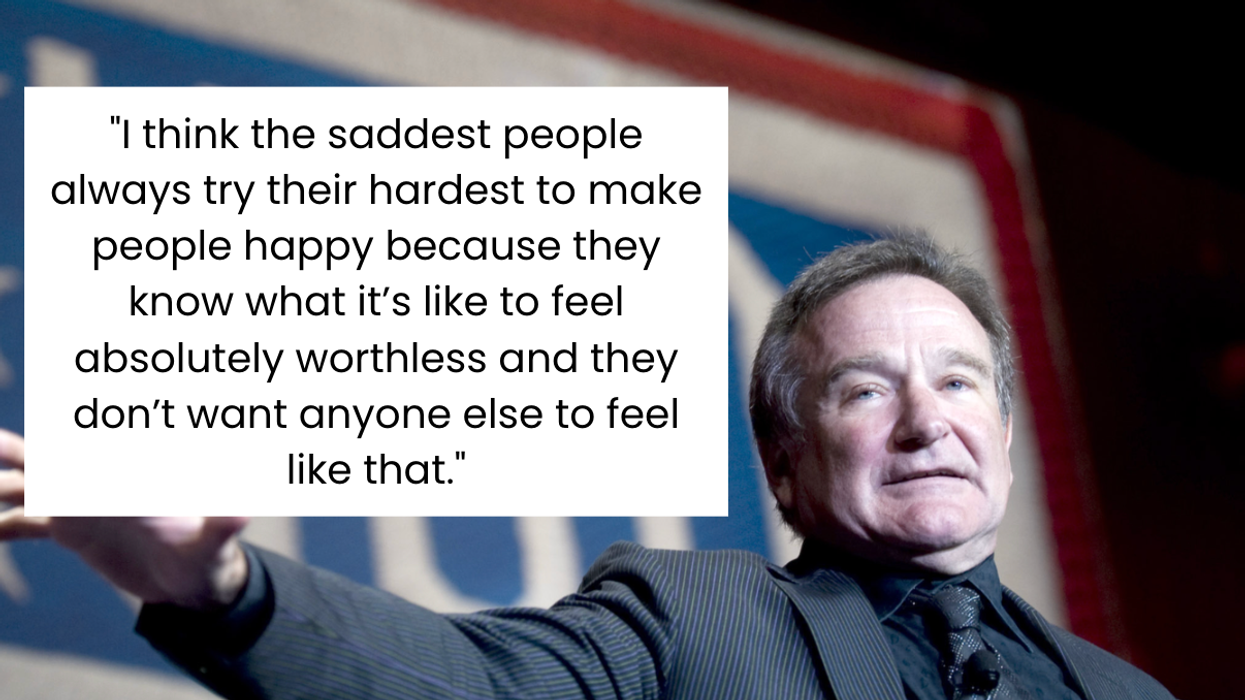

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007 Gif of Robin Williams via

Gif of Robin Williams via

People on a beautiful hike.Photo credit:

People on a beautiful hike.Photo credit:  A healthy senior couple.Photo credit:

A healthy senior couple.Photo credit:  A diverse group of friends together.Photo credit:

A diverse group of friends together.Photo credit:  A doctor connects with a young boy.

A doctor connects with a young boy.  Self talk in front of the mirror.Photo credit:

Self talk in front of the mirror.Photo credit:  Lightbulb of ideas.Photo credit

Lightbulb of ideas.Photo credit

Superstructure of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, 2007

Superstructure of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, 2007