During my final semester of college, a time when most students are thrilled by the prospect of graduating, I slipped into a deep depression for no apparent reason. Despite the fact that I was graduating with honors, that I had a bright future ahead of me, and that I had a loving partner who supported me, I felt hopeless and spent long afternoons imagining how I might be able to disappear. I saw therapists, read just about every self-help book, exercised, ate right, meditated, and took more Ativan than seemed humanly possible, but nothing seemed to help. No one could figure it out. I distinctly remember taking a sound bath yoga class led by a woman named Deborah (pronounced Deb-bore-ah), and while holding hands with a stranger humming a funereal drone, I thought, this is no place for a depressed person.

On a whim, I decided to go off birth control for a while. I’d been on it for years and figured it couldn’t hurt. Within a week, I felt as if a physical weight had been lifted. I mean, physically I lost the five pounds of bloat I’d been carrying around as a result of the pill, but mentally I felt lighter as well. I could breathe again. And while I don’t believe hormonal birth control pills were the sole force driving my depression, I do think they catalyzed underlying issues.

Now science seems to agree. According to a study recently published in JAMA Psychiatry, hormonal contraception can increase a woman’s risk of depression. After studying more than 1 million women and teenage girls between the ages of 15 and 34 over the course of about six years, Danish researchers found that the role birth control plays in mental health has been understated. Out of the 55 percent of participants who reported using birth control, many were prescribed antidepressants over the course of the study.

Though not all forms of birth control are created equal. Study participants using combination birth control pills—the kind that have both estrogen and progestin—were 23 percent more likely to take antidepressants as compared to those who didn’t use hormonal contraception. Progestin-only pills seemed to have an even bigger impact on antidepressant use, with 34 percent of users being more likely. And antidepressant use increased by 40 percent for those using a progestin-only IUD, 60 percent for vaginal ring users, and an alarming 100 percent for those using a patch.

To be clear, this study does not by any means indicate that all women who start using pills, rings, or patches are bound to become depressed. In fact, only about 12.5 percent of participants—users and non-users alike—started taking antidepressants at some point during the course of the study. Not all women diagnosed with depression end up taking antidepressants and not all women who report feeling depressed receive an official diagnosis.

What does seem clear is that teenage girls are particularly at risk. Lead author and clinical professor Øjvind Lidegaard stressed the importance of doctors informing their patients of the risks and various low-estrogen options, telling Health,

“Doctors should include these aspects together with other risks and benefits with use of hormonal contraceptives when they advise women to which type of contraception is the most suitable for that specific woman. Doctors should ensure that women, especially young women, are not already depressed or have a history of depression and they should inform women about this potential risk.”

Ultimately, it’s up to women to listen to their bodies and minds and to pay acute attention to lifestyle changes that may be having a negative impact. If you’re feeling down and can’t figure out why, maybe it’s time to rethink your birth control plan as it could be a contributing factor. Many women, myself included, make the mistake of feeling guilty or ashamed about being depressed, despite the fact that it may be out of their control. Though it’s only the start of understanding how hormones and mental health relate, what this study does is empower women to investigate their options. In the same way birth control empowered women to take control of their health in the 1960s, women today have the power to choose what works best for them as individuals.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

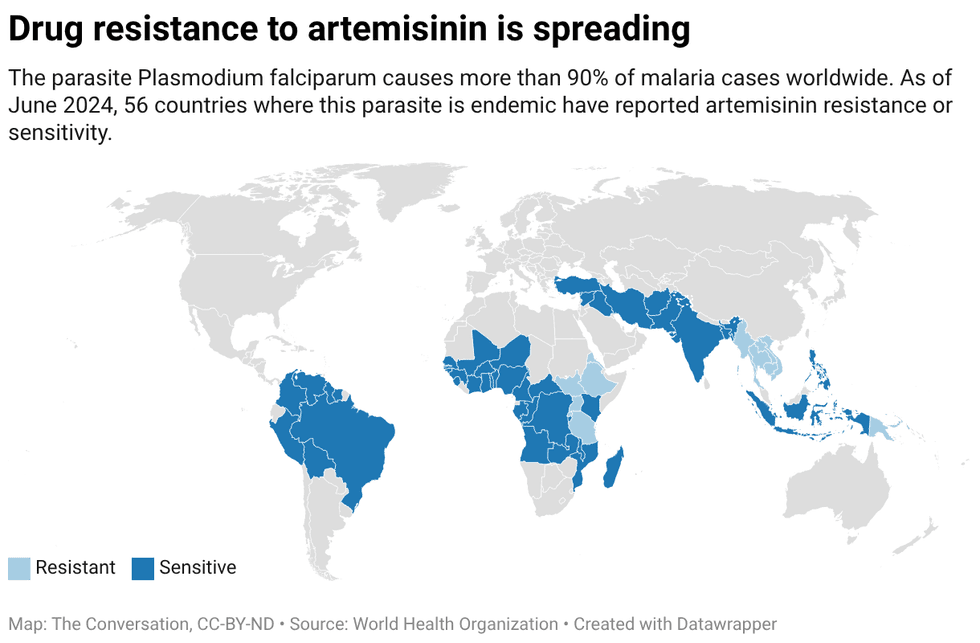

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

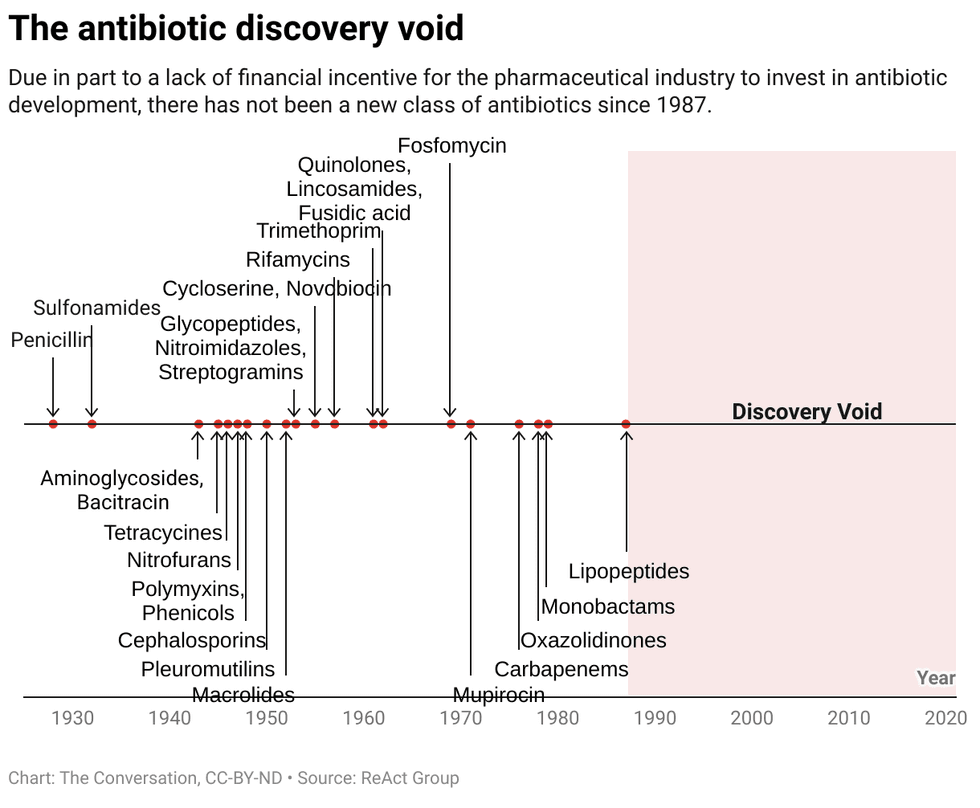

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.