SANELISWE RADEBE was alone in the living room when the gunmen arrived. Sitting on the sofa watching TV, the slender 17-year old heard a vehicle crawl toward the house in low gear. It was March of 2016, near the end of the South African summer, and already dark outside at 7:30 p.m. A blue light flashed through the curtains. “It’s the police. We’re looking for Bazooka,” one of the men shouted, thumping on the front door.

Bazooka Radebe, Saneliswe’s father, was in an adjacent room. He had taken his trousers off after work, like he did most evenings, and was dressed in a black shirt and underwear. He didn’t emerge when Saneliswe shouted for him, so the boy opened the front door. The two men wore gloves and plain clothes. One carried an assault rifle, the other a pistol. They lifted their weapons and shoved Saneliswe backward, forcing their way inside. “We’ve come to arrest your father,” they said, looking around at the empty chairs.

Bazooka’s son cried out once more—“There are people here! They say they are police!”—and watched as the men made their way down the tiled corridor. Bazooka was still in his underwear when the men hustled him outside.

A stolen white hatchback idled outside, the flashing blue light temporarily affixed to its roof. The actual owners of the automobile were two teenaged boys, tourists who had been held up by the fake cops near Port Shepstone, a wealthy resort town roughly 40 miles up the coast. One of the teens sat tightly bound in the car’s back seat, witnessing the scuffle. The other lay in the trunk, stuffed out of sight.

The car’s headlights illuminated Bazooka’s rural home—a large single-story structure with patches of bare plaster, facing a scrapyard strewn with machinery and trash—the sort of building that, though comparatively grand in a poor neighborhood, seems permanently incomplete. The vehicles cluttering the property were evidence of Bazooka’s success as an entrepreneur, taxi boss, and mechanic—trades he’d used to lift himself from a life of poverty.

As Bazooka struggled with the intruders in the driveway, Saneliswe remained in the house, first dialing Tarzan, his 28-year-old brother, and then the local police station. Moments later, Saneliswe heard several gunshots, then a car speeding off. He stepped into the yard and saw his father sprawled on the ground, bleeding into the dirt. By the time Tarzan arrived 20 minutes later, his father was already dead.

Forensic pathologists later determined that Bazooka had been struck three times on the forehead with a blunt object, before being shot in the chest, abdomen, and back of the head.

I meet his sons at the house where their father was killed. Tarzan does most of the talking. Younger brothers Saneliswe and 18-year-old Khulile slouch next to each other on the sofa. “They shot him right where that car is,” Tarzan says pointing to an old BMW parked outside the front door. The personalized license plate on it reads: S RADEBE.

Bazooka Radebe’s given name was Sikhosiphi, but everyone knew him as “Bazooka,” a name he’d earned for his physical prowess on the soccer field. At age 51, with an ample belly, Bazooka’s days on the pitch were long behind him, but he remained a vigorous force in the community. As chairman of the local taxi association, he held a coveted position of power in a sector plagued by turf wars and mob rule. Over the years, he had become accustomed to the threat of violence. But it was Bazooka’s role in a different struggle, linked to the tribal lands he’d grown up on, that made him particularly wary in the months preceding his death. Since the early 2000s, an application to mine titanium from dunes near Bazooka’s home village of Xolobeni, and the surrounding area of Pondoland, has fueled an increasingly violent conflict. Proponents of the mine argue that the titanium sands—raw materials for manufacturing such diverse products as paint, sunscreen, metal alloys, and ceramics—would bring jobs, infrastructure, and money to the chronically underdeveloped region. Opponents like Bazooka, a respected leader in the fight, countered that mining would damage the environment, threaten traditional livelihoods, and enrich only a minority of the population without offering any long-term economic benefits.

The dunes, tarnished a deep red, roll for more than 10 miles down South Africa’s coast. Up close they are flecked with shiny black dust, like iron filings—traces of the space-age minerals now coveted by big industry. Proposals call for scraping up the sands with heavy machinery and transporting them to a wet separation plant that would suck up four billion gallons of water each year. Other ancillary infrastructure would include cables, pipelines, offices, hostels, and warehouses. Proposed roads for trucking could potentially cut through 60 miles of farmland and villages.

According to activists, mining the dunes would also displace at least 500 people, restrict access to communal fields, threaten food security, deplete fresh water, sow disorder by attracting migrant workers, and cause the “breakdown” of customary practices. “Mining would have profound and far-reaching negative impacts (on) livelihoods, ways of life, environment, and land rights,” states a formal objection by lawyers representing the activists.

Bazooka was unimpressed by the mining proposals, and in 2007 helped form a vocal anti-mining activist group called the Amadiba Crisis Committee, serving as its chairman. His prominent role in the movement would make him a major obstacle to the proposed multimillion-dollar project—and plausibly a thorn for residents who were paid large sums by a foreign mining company to ensure that the project went ahead.

For more than two decades, an Australian company called Mineral Commodities Ltd, or MRC, attempted to mine the area, tasking its South African partners with obtaining community support. Members and allies of the main partnering firm—the Xolobeni Empowerment Company, better known as Xolco, which was bankrolled via a multimillion dollar loan from MRC—have been linked to multiple cases of violence and intimidation against antimining activists, including the murder of Bazooka Radebe, according to his family and several supporters. No direct evidence has been found incriminating MRC or its subsidiaries in the assassination, but years of unresolved strife point to a compromised and ill-considered relationship between the mining firm and its local representatives: a lucrative business proposition, out of touch with community concerns, that spun out of control.

In a statement issued a few days after Bazooka’s death, the publicly traded conglomerate, responding to unfavorable media coverage and widespread public outcry, denied being “implicated in any form whatsoever” in the attack, insisting, “The company under no circumstances has, or ever will, condone violence in any form.” But MRC’s track record in South Africa is blighted by accusations of bribery, threats, and assaults connected to people directly associated with the company and its partners. For years, MRC had managed to distance itself from any incriminating incidents. This began to change after Bazooka’s death.

The gunmen who killed Bazooka escaped that night in March and the case has yet to yield any arrests. Fearing conspiracy, Tarzan and his family have stopped sharing information with detectives. “My father was a powerful man,” Tarzan says. “It isn’t easy to kill someone like that and not be caught. The people who did this had lots of money. There’s only one thing that’s brought big money to this area. The mining issue led to the death of my father.” (Local authorities did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Feeling let down by the justice system, the Radebe family fears more violence, entangled in a complicated, corrupt power struggle that spans generations, threatens acres of precious land, divides neighbors, and endangers many more lives.

BAZOOKA GREW UP in Pondoland, a deeply rural region of South Africa’s east coast. Round huts with thatched roofs dot the hills, where children herd cattle through waist-high grass. Pondoland is the traditional home of the Mpondo people, a tribal kingdom with roots extending back more than 300 years. It was annexed by European settlers at the end of the 19th century, later becoming a “native reserve” of the colonial South African state. From 1913 until 1991, black South Africans could only own land within ethnically demarcated “homelands” such as these, which added up to less than 13 percent of the country’s surface. White people, who made up less than one-fifth of the population, controlled 80 percent.

Despite this history of dispossession, or perhaps because of it, Pondoland residents maintain a deep connection to the ground. Most practice subsistence agriculture, cultivating food crops—maize, sweet potatoes, bananas, sugarcane—and grazing their livestock on communal fields. The area is poor in monetary terms, even by the standards of South Africa, where half of the total population of 50 million lives below the national poverty line of $53 per month. But in Pondoland, the effects of this hardship are attenuated by traditional livelihoods, which have been preserved by geographic isolation and strong community ties. For many residents, land—one of South Africa’s most contested resources, still unequally distributed 22 years after apartheid ended—holds more value than money.

In the 1960s, Mpondo villagers rose up in violent protest against their chief, who had been co-opted by the apartheid government and began imposing an unpopular agricultural “betterment” scheme—limiting herd sizes, erecting fences, and resettling farmers from overgrazed areas. Today, residents opposed to mining say they are engaged in a repeat of that struggle, fighting to maintain sovereignty over their property.

South Africa is the world’s second-largest titanium ore producer after Australia, the first step in a complex supply chain that yields thousands of modern products. The sands around Pondoland hold the tenth largest heavy mineral deposit in the world, according to MRC. The company applied for the rights to an area measuring some 2,900 hectares, with plans to actively mine 885 of that—roughly two and a half times the size of New York’s Central Park. The Xolobeni Mineral Sands Project, named after Bazooka’s home village located inland from the dunes, promised to create 600 full-time jobs and last 22 years, supplying some 10,000 tons of raw material for the global titanium market. MRC promised that the community would see tangible social and economic benefits from these operations, writing in its 2014 annual report that the proposed payoffs “(showed) beyond doubt that responsible mining can make a significant contribution to sustainable development”—despite the fact that no mining had yet taken place.

The concept of sustainable development, and who gets to define it, has underpinned the Xolobeni dispute from the start. MRC’s interest in the deposits began in 1996, when an unrelated sand mining company allowed its prospecting license for the area to expire. According to John Clarke, a South African social worker who has documented the mining conflict for more than 15 years, MRC Executive Chairman and CEO Mark Caruso negotiated a multi-million dollar deal with the South African government to begin sampling the titanium sands. The government had recently adopted a set of neoliberal policies in an attempt to boost economic growth, switching from the broadly socialist approach of Nelson Mandela’s first democratic government, elected in 1994. An important part of the new strategy was attracting foreign investment—particularly in the mining sector, South Africa’s founding industry.

By 2002, MRC was confident that the deposits were rich enough to mine, and began raising capital. The company was listed on the Australian Securities Exchange and they canvassed for investment from shareholders. MRC also set up Tormin, a mineral sands mine on South Africa’s west coast. Just over a decade later, in 2015, Tormin became the site of violent protests, during which one MRC manager allegedly drove into a mineworker and another fired live ammunition into the air. Following the unrest, Caruso wrote in an email that he would “rain down vengeance” on anybody who opposed his company, quoting in full the biblical verse most famously uttered in Pulp Fiction: “And I will strike down upon thee with great vengeance and furious anger, those who attempt to poison and destroy my brothers. And you will know my name is the Lord when I lay my vengeance upon thee.” Critics say that this level of aggression has typified Caruso’s approach for many years.

[quote position="full" is_quote="false"]Although no longer classified as a tribal reserve, Pondoland is still governed, at the local level, by traditional authorities: a royal family, regional chiefs, and village headmen and headwomen.[/quote]

To operate in South Africa, companies like MRC must partner with black-owned firms to comply with national Black Economic Empowerment legislation. This system aims to address years of injustice under the apartheid era by redistributing capital to black entrepreneurs. Xolco formed in 2003 to fulfill these requirements. Xolco was founded by Mark Caruso’s brother, Patrick, in conjunction with an attorney named Maxwell Boqwana and Zamile Qunya, a local businessman and former mayor with close ties to the country’s ruling African National Congress party. Before aligning with MRC, Qunya managed a successful ecotourism venture called Amadiba Adventures, which offered tours by horseback and guided hikes. The project fell apart shortly after Xolco was established, despite receiving $8 million in grant support from the European Union. MRC has repeatedly pointed to the failure of Amadiba Adventures to motivate public support for mining.

Xolco’s 26 percent shareholding in the proposed Pondoland mine, worth more than $20 million today, was financed with a loan from MRC. Xolco must repay this money with proceeds from any future mining operations, meaning the financial benefit of its members—several of whom have been accused of violence since the company was established—depends squarely on the project moving ahead.

According to MRC, Xolobeni residents welcome mining on their land. The company’s 2006 shareholder report claimed that communities “(continued) to unanimously support” the project. In 2015 MRC said progress had been made mediating between promining and antimining groups. In reality, MRC was unable to obtain an operating license due to strong opposition. This didn’t stop the company from trying to get its application approved. While MRC persisted, local conflict over the issue grew worse, driving a wedge through the very communities that mining was supposed to uplift. Bazooka’s death was not the first linked to the titanium sands conflict, according to activists. At least three fairly high-profile cases (one shooting and two deaths that may or may not have been poisoning) remain unsolved.

A YOUNG WOMAN from a village near Xolobeni sits in front of a table laden with grilled meat. It’s July, the day of her coming-of-age ceremony. Her father has slaughtered a pig and six cattle, a grand gesture in a region where livestock are prized markers of status and wealth. Traditionally, the entire village would of have joined in, but few guests attend this feast. The father recently switched sides in the mining dispute, announcing his support for the project, and many neighbors have boycotted his invitation as a result. “We ate as much as we could, but some of the meat went bad,” one relative tells me. “Something like this would never have happened before.”

Mining is now the biggest issue dividing people in Xolobeni. Although no longer classified as a tribal reserve, Pondoland is still governed, at the local level, by traditional authorities: a royal family, regional chiefs, and village headmen and headwomen. Issues are usually discussed at weekly tribal council meetings called komkhulu, where participants reach decisions by consensus. But instead of taking their proposals to these forums, the mining lobby has co-opted local leaders, turned residents against one another, and “engaged in organized campaigns of violence,” according to a formal objection to the mining application lodged by lawyers representing the Amadiba Crisis Committee in March—the same month as Bazooka’s murder.

In return for signatures supporting mining, Xolco has on many occasions distributed gifts like food parcels, school uniforms, and sewing machines to residents. But the most flagrant example of cultivating favor was the 2015 appointment of the region’s senior traditional authority as a Xolco director.

Chief Lunga Baleni, born into an old ruling clan, used to be a fixture at tribal council meetings, but villagers seldom see him anymore. Now, he resides in a distant wealthy suburb. When he does frequent Xolobeni, where he once lived, he drives around in a Ford pickup truck given to him by MRC. Though he originally held a neutral position in the dispute, Chief Baleni began placing heavy pressure on his subordinates to support MRC’s ambitions. In 2014, he attempted to disband the komkhulu of one village, Mdatya, because its elders resolved not to back the project. This set in motion a particularly violent sequence of events.

Late one night in December 2015, Mdatya’s headwoman, Cynthia Baleni, heard a group approaching her homestead. (She hails from Chief Baleni’s clan, but is not a close relative.) Months earlier, she had refused a backroom order by Chief Baleni to overrule her komkhulu’s decision. Hiding in nearby bushes with her three children, she heard gunshots as the group searched her property. The following night, the group returned, firing into the air yet again.

This intimidation was just the beginning of two weeks of unrest, according to a statement delivered to police by Amadiba Crisis Committee leader Nonhle Mbuthuma this February. Mining supporters allegedly raided homes across the village, ambushing activists, firing weapons, and kicking down doors. The statement also detailed separate episodes of violence, accusing Zamile Qunya’s younger brother Bashin of assaulting a 61-year-old woman during a 2015 attack on mining opponents and describing a 2016 incident when supporters interrupted a community meeting and “waved firearms around,” threatening to shoot.

The December raids were especially frightening for antimining activist Busisiwe Ndovela, 40, whose homestead lies a mile from the village headwoman’s, on a low hill within earshot of the sea. Shortly before dusk on New Year’s Eve her family prepared to sleep outdoors once again, a precaution they’d been taking since the violence began. Heavily pregnant, Ndovela wrapped her six children in blankets and packed food into tins. She said goodbye to her husband, who remained behind to protect the home, and set off with her sister and mother-in-law, walking slowly. It took two hours to reach the forest patch where they would stay the night.

At 3 a.m., Ndovela’s water broke. The women quickly moved the children out of sight while Ndovela lay down on a rock and went into labor. She gave birth two hours later, at sunrise, and was hauled home on a wooden ox sled. The following night, she returned to the forest with her newborn child.

“We’re still afraid,” Ndovela admits one evening in June. Her baby, a chubby girl named Axola, bounces on her hip. The older children sit quietly on a bench close by as the light fades. Ndovela’s husband has gone drinking at a nearby tavern. Their homestead, unfenced, feels isolated. “The people responsible for those raids are still free,” she says. “They still have weapons. But I haven’t changed my mind. I disagreed with mining in the first place; now I hate it even more.”

Police arrested four men after the December raids, charging them with attempted murder. One was an employee at MRC’s west coast mine. A Xolco director and Chief Baleni bailed the suspects out an hour after their arrest.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]I fought for this land. I’ll fight for it until I die... I feel like taking up a spear again. People can cut my throat if they like.[/quote]

SAMPSON GAMPE, 86, is a veteran of the 1960s revolt known as the Pondo Rebellion. He’s a committed antimining activist. He has 2 wives, 10 children, 45 grandchildren, and 15 great-grandchildren. An inyanga, or traditional herbalist, Gampe recounts how policemen broke his hand during the uprisings, stomping him with their heavy boots when he attempted to grab an officer’s gun.

“I fought for this land,” he says. “I’ll fight for it until I die. These boys who support mining are cowards, attacking people at night. They’ve been confused by money. I feel like taking up a spear again. People can cut my throat if they like.”

But at a tavern near Gampe’s homestead one Saturday afternoon, a young traditional healer named Beauty says that people opposing the mining project are ignorant. “People are sitting at home right now without jobs,” she tells me. “This area is poor. Mining will change that. People won’t have to go into the cities to get work.”

Around the corner from the tavern, I speak to two men who worked at MRC’s Tormin mine. Vumelakhe Ndovela, 49, says that people who disagree with mining are “lazy” and “jealous” of the benefits the Xolobeni project would bring. Both men are wearing MRC overalls, but Ndovela tells me he lost his job in March.

“I have a problem with the company’s management, though I support mining 100 percent,” he says. “They were racist. They disrespected us. But that’s not a mining issue. It can happen in any industry.”

Following protests at Tormin last year, in which complaints about racism featured prominently, employees reported that the mine’s general manager, Gary Thompson, would tell them, “If you go inside the gates, you’re in Australia.” Around 40 Pondoland residents received jobs at Tormin, more than 900 miles away, via Xolco’s Zamile Qunya.

When I attempt to contact Qunya, he refers me to Zeka Mnyamana, his unofficial spokesman. Mnyamana, 42, is dressed in a pinstriped shirt and leather shoes when I meet him at a spaza shop (convenience store) far outside the village. Once a tour guide with Amadiba Adventures, and formerly opposed to mining, Mnyamana was kicked out of his family home for switching sides. He tells me that he sees no conflict between mining and traditional livelihoods. “This land is beautiful and we care about it,” he says. “South Africa needs investment. The government can’t afford to build roads. People here are drinking water from rivers, with the animals. Our eyes haven’t opened yet.”

Coverage of the mining conflict has been “one-sided,” Mnyanama continues. I mention that I’ve been struggling to get in touch with mining supporters and ask if he might help me set up further interviews. “Nobody on our side wants to talk,” he says. “People are afraid of the activists.”

When pressed for details, he says that mining opponents “attacked” three households in December, in the very same village where Busisiwe Ndovela gave birth outdoors. Later in our conversation, he says that people had merely been “singing and marching” outside the homes of mining supporters, warning them to leave the area or risk having their property burned. This isn’t the only time Mnyamana revises his statements to me. When asked what he does for a living, he tells me he is unemployed and that his wife, a seamstress and designer, supports their eight children. Shortly after, he says he has worked for Tormin for the past three years. “I still work for them,” he adds, bursting into a giggle after realizing that he’s contradicted himself. “I work from home. I write emails and reports to Mark Caruso.”

Mnyamana categorically states that neither he nor Xolco have ever received any money from MRC. He drives away in a Ford SUV, declining to be photographed beside the vehicle because “people would think it came from the mine.”

MRC declined to comment, including a request to clarify their current relationship with Mnyamana. Spokesperson Anne Dunn said that the company was “disappointed” with how journalists had portrayed the conflict. (Responding to allegations of indirect responsibility for Bazooka's murder, Caruso later said, “MRC emphatically rejects both of these unsubstantiated allegations as being without any merit, speculative, provocative to the point of irresponsibility, and highly defamatory.”)

But opposition to mining stretches beyond community dissent and includes broader environmental factors. Coastal Pondoland falls within a global biodiversity hotspot and is a renowned center of plant endemism, home to some 200 species found nowhere else on earth. Two of the three free-flowing rivers in Xolobeni have flagship status on the National Freshwater Ecosystem Priority Areas atlas. The region also falls within a national marine protected area. These ecological assets have both attracted outsiders to the antimining movement and given mining supporters an easy opportunity to dismiss them as “greenies,” unconcerned with the need for social and economic development in Pondoland—an allegation that draws on ample historical precedent, however facile and self-serving it may be.

These social and ecological objections did little to deter MRC’s pursuit of the dunes. The company came closest to receiving a mining license for Xolobeni in 2008. South Africa’s minister of minerals and energy at the time, Buyelwa Sonjica, announced that she would soon be awarding the company operating rights. Sonjica’s decision ignored a 2007 report by the South African Human Rights Commission, an independent body tasked with protecting constitutional rights. The investigation found that a “vast majority” of residents were opposed to the project and that MRC had not adequately consulted or informed community members. Nevertheless, Sonjica arranged to visit Xolobeni to officially present the news to the public.

At the announcement, a group of 100 protesters representing the Amadiba Crisis Committee, “disrupted proceedings,” according to news reports. In response to the interruption, Sonjica blamed “rich white people” for dividing the community. “Why do we need permission to mine natural resources? Why do we have to wait for people to teach us about nature? They come here to play while we are hungry,” she said.

Conservation in South Africa has had a recurring pattern of serving white interests at the expense of communities. The Kruger National Park, South Africa’s largest and best-known game reserve, was established in 1898 after evicting black villagers; it is named after Paul Kruger, a white Afrikaner nationalist whose political career laid the foundation for apartheid. Historian Jane Carruthers has argued that the park, as a symbol of broader conservation efforts in South Africa, represents “white political and economic domination” for many black citizens, rooted in years of colonial conquest. In Xolobeni, this legacy continues to influence debates.

But largely thanks to the efforts of outsiders, MRC never received its mining license. The Amadiba Crisis Committee’s lawyers lodged a formal appeal in September 2008, arguing that the company had conducted deficient environmental impact assessments and a “fatally flawed” community consultation process. The appeal included evidence of Xolco submitting a petition with more than 3,000 forged signatures. In June 2011, after a series of delays, the government withdrew the mining rights, allowing MRC a 90-day response period. The company submitted a new application aimed at addressing these issues in March 2015, setting in motion a fresh round of protests that culminated, eventually, in Bazooka’s murder.

It’s difficult for rural communities to oppose development projects without legal and strategic support. This is not only true in South Africa, but across the developing world, where conflict associated with extractive industries has increased in recent decades. In 2014, at least 116 environmental activists were murdered in 17 countries at an average of two people per week (more than twice the number of journalists killed during the same period), according to human rights watchdog Global Witness. In Pondoland, villagers opposed to mining have forged strong bonds with civil society and the media, enabling them to challenge MRC and its local partners. They have also fought proposals to route a new 250-mile toll road through their lands since the early 2000s—a scheme many see as directly linked to the mining project. These twin struggles have generated hundreds of newspaper articles, a book series, and a feature-length documentary, but have not yet brought the freedom from interference that so many residents desire.

BAZOOKA’S FUNERAL, held in his village 11 days after the attack, drew more than 2,000 mourners—the biggest in Pondoland in recent memory. Dissatisfaction with police response to the conflict was growing. A week earlier, the investigating officer assigned to Bazooka’s murder case had released the hijacked vehicle back to its owners before forensic experts could collect evidence. The provincial head of a special investigative unit called the Hawks was “flabbergasted” when he found out, according to lawyers familiar with the case. Three weeks later, police had still not interviewed the teenage boys who were taken hostage by the men, one of whom witnessed the shooting.

More irregularities followed during Bazooka’s autopsy. The Amadiba Crisis Committee’s lawyers had requested and paid for an independent forensic examination—relatively standard practice in high-profile South African murder cases. Police officers reportedly placed great pressure on Bazooka’s family to allow hospital staff to proceed with the postmortem instead. Tarzan recalls how the investigating officer had asked why the family wanted the bullets removed from Bazooka’s body. “He asked me what I would do with the bullets afterwards. I knew right then that this investigation wasn’t going anywhere,” Tarzan says. A hospital assistant, untrained in specialist forensics, had already cut Bazooka’s chest open before officials agreed to postpone the autopsy.

“We put our trust in the police. We thought the killers would be behind bars by now,” Tarzan says. “That’s been the most difficult thing to deal with.” Particularly troubling for him has been the authorities’ apparent unwillingness to pursue certain leads. Two weeks before the murder, Tarzan tells me, Bazooka was contacted by Qunya, his main opponent in the mining dispute. “Qunya warned my father to get rid of any unlicensed guns on the property, because there was soon going to be a police raid,” Tarzan says. “How would he have known that?” Taking this as a threat to disarm, the family grew warier. Bazooka warned other committee members to vary where they slept. Though Tarzan shared this information with authorities, he still doesn’t know if Qunya was ever taken in for questioning. Police did not respond to written questions despite multiple requests for comment. When I called Qunya, he denied that this meeting took place.

Tarzan has inherited Bazooka’s taxi fleet. I meet him at the Port Edward taxi rank, a marginal, trash-strewn transit yard across the road from a large shopping complex. Tarzan arrives in a rusting van, guarded and suspicious. He’s been told that two white men are asking questions about Bazooka and taking photographs. Both he and his uncle, who also owns several taxis, have received death threats since the murder. Later, Tarzan explains that Bazooka’s former taxi rivals are trying to take over the industry. As chairperson of the local taxi association, Bazooka wielded power that others resented, “but his enemies weren’t powerful enough to take him out by themselves,” Tarzan says. “They needed to join forces with other people.”

A few months before his murder, at the same taxi rank, Bazooka had seen a leading Xolco member in conversation with a group of rival taxi owners, Tarzan recalls. “That man owns no taxis, so my father asked him what business he had there.” Tarzan says. (The Xolco member’s name has not been printed due to the sensitive nature of this case.) “To me, it’s obvious what happened next.” Tarzan believes that an alliance formed between a local faction of mining investors and embittered minibus owners which resulted in his father’s death.

IN MID-JULY, two weeks after declining to answer questions for this article, and nearly four months after Bazooka’s assassination, MRC announced that it was divesting entirely from the Xolobeni project. “In light of the ongoing violence and threats to the peace and harmony of the local community, the company accepts that the future viability of the Xolobeni Project should be managed by (South African) stakeholders and organisations,” MRC wrote in a statement. But activists are concerned that the company will remain indirectly involved in future titanium mining projects, which the South African government seems set on supporting.

MRC intends to sell its shares to a little-known Xolco subsidiary called Keysha Investments. It is not yet clear how this transaction, worth millions of dollars, will be funded. Residents in Xolobeni learned of the decision via MRC’s public announcement. Keysha Investments only listed director is “entirely unknown in the community,” according to a statement by lawyers representing the Amadiba Crisis Committee.

Two days after the announcement, at an overdue public meeting to address complaints about violence and intimidation in Xolobeni, South Africa’s Deputy Minister of Mineral Resources, Godfrey Oliphant, told residents that the government, not the community, would decide if mining went ahead. “Don’t appropriate power to yourselves,” he warned.

The meeting was unduly festive, bolstered by loud music, dancers, and free food—“a police-a-palooza,” in the words of a local schoolteacher in attendance. After making speeches that didn’t mention Bazooka’s death once, the government delegation, which included the deputy police minister, allowed community members to ask 10 questions. Mining supporter Zeka Mnyamana rose to speak first, saying that his community was still in favor of the project. The meeting erupted in furious protest, and government officials were escorted out by riot police.

Not long after, I call Tarzan to ask what his family has made of the news. “Nothing has really changed with the mining,” he says. “The Australian company is selling their shares, and the locals they’ve been working with are taking over the project. In a few years the Australians may be back. Our fight isn’t over.”

But two events may give Tarzan and his allies cause for optimism. This past September, the South African government issued an 18-month moratorium on all applications for mining and prospecting in the Xolobeni area due to “significant social disintegration” and the “highly volatile nature” of the conflict. Later that month, lawyers representing the activists once again filed papers, this time to a high court, seeking to prevent officials from awarding mining rights without express community consent. If the application is successful it will set a precedent for other communities in South Africa, forging an important safeguard for customary land tenure. That would go a long way toward securing a fairer and less fragmented society—but it will not erase the expense of a life.

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A home pregnancy test Canva

A home pregnancy test Canva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

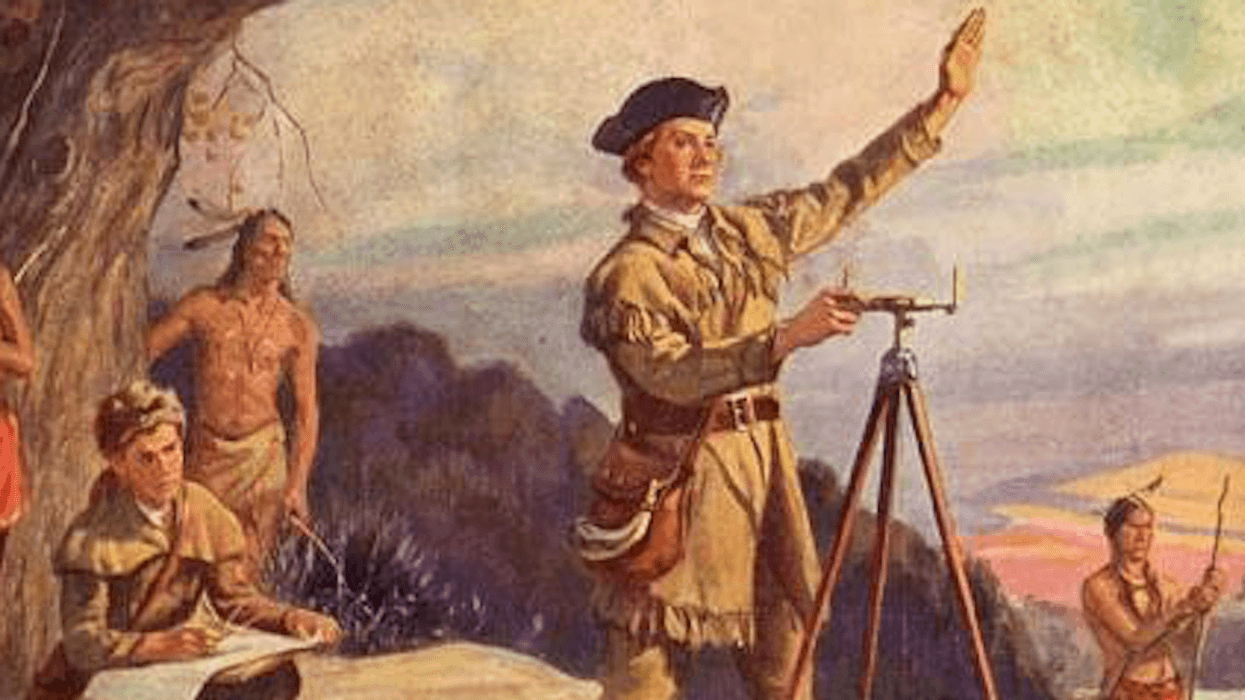

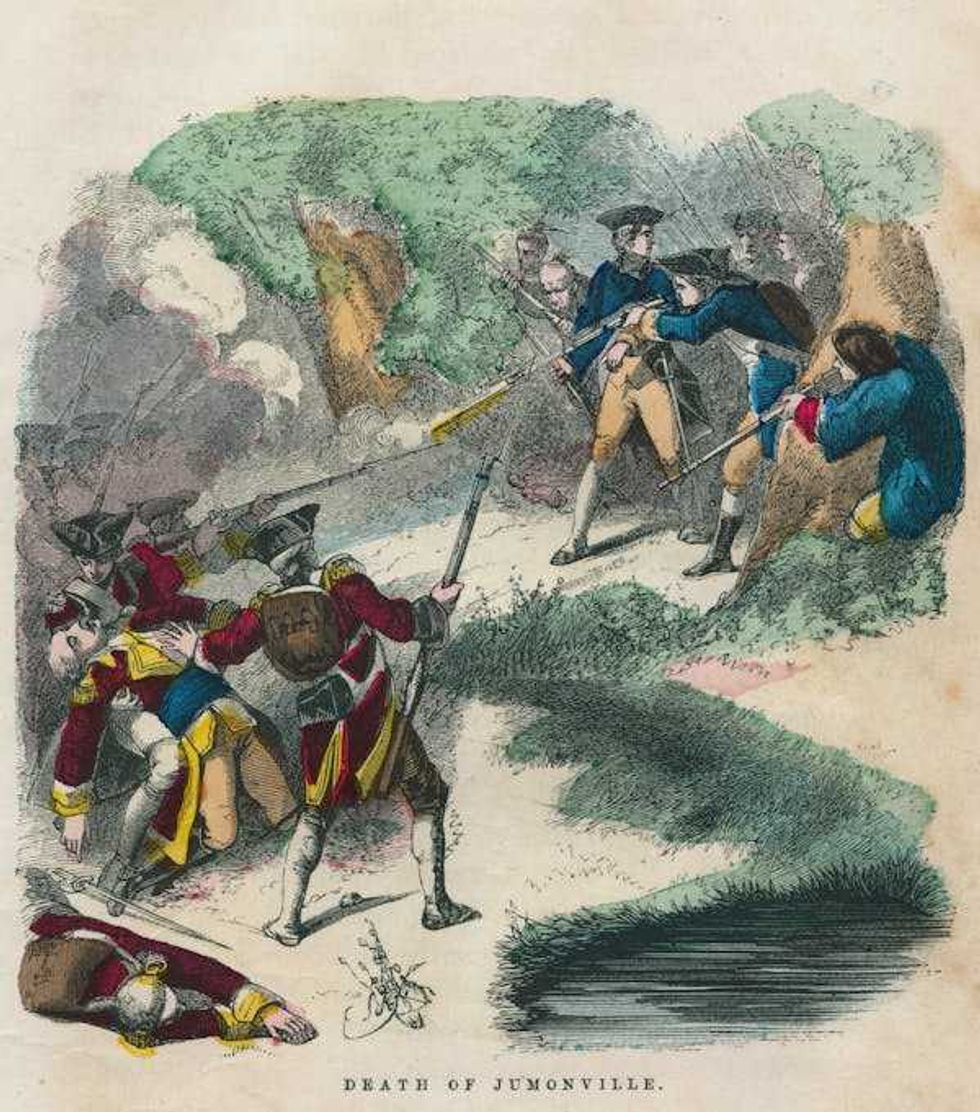

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War.

The Jumonville affair became the opening battle of the French and Indian War. Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity.

Washington was outnumbered and outmaneuvered at Fort Necessity. A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A log cabin used to protect the perishable supplies still stands at Fort Necessity today.

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via

Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via  Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via

Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via