When you bite into a xiaolongbao, you may wonder at the miracle of creation and construction that holds a mouthful of velvety broth inside a seemingly delicate, semi-transparent dumpling skin. The secret is that the pork filling, seasoned with ginger and Shaoxing wine, is mixed with pork aspic that melts on cooking, transforming into an aromatic soup. But have you ever considered where xiaolongbao come from and who invented them?

In Shanghai, where I lived for many years, locals solidly stake xiaolongbao (also known as soup dumplings) as their own invention. My old friend, Qiu Yibo, Shanghai born and raised, says, “In my mind, xiaolongbao is local Shanghai food. Ever since I was born, my parents have told me xiaolongbao is from Shanghai.” Every Shanghai restaurant serving local cuisine makes its own xiaolongbao, often called simply tangbao. Some are famous, like those from Jia Jia Tang Bao, filled with succulent pork and the rich yellow roe and sweet flesh of Shanghai’s hairy crabs. Others are local secrets, like those from Guang Ming Cun or The Humble Room in the former French Concession. “We eat them very frequently as breakfast,” adds Qiu. In fact for the Shanghainese, a steamer basket of xiaolongbao might equally be lunch, dinner, or a late-night snack.

It's likely their origins are from Nanxiang, where they’ve been making xiaolongbao for more than a century. A hundred years ago, Nanxiang was a neighboring village, but as Shanghai sent out tentacles in every direction, Nanxiang became subsumed and is now relegated to the status of an outer suburb, with its own stop on the Shanghai metro. It’s considered by many to be the ancestral home—even the spiritual home— of xiaolongbao, with its Ming dynasty garden, old stone-walled canals, and ancient temple. Xiaolongbao lovers make the pilgrimage from all over China to get to the source, and Nanxiang’s old streets are lined with dumpling shops rolling, stuffing, and pleating xiaolongbao into shape. Nobody knows exactly who started making them first, but it could well be 100-year-old Song Ji restaurant, on the edge of Guyi Gardens, where stacks of steamer baskets full of plump xiaolongbao wait to be cooked in the giant outdoor steamer. Inside, round wooden tables are filled with Shanghai locals, dipping their xiaolongbao in dark vinegar before slurping up the filling. These xiaolongbao have a simple, homemade quality. The skins are thicker because they’re hand-pressed rather than rolled, and the filling is more rustic, with less seasoning and more meat.

More than 70 years after Nanxiang’s cooks started making xiaolongbao, a refugee from China’s Shanxi province arrived in Taiwan in 1949, just as the communists came to power under Mao Zedong. Yang Bingyi ran a tiny cooking oil business in Taipei, but when business faltered, his wife Lai Penmei started to make soup dumplings on the side to supplement their income. The soup dumplings proved more lucrative, and their “humble stall” became the first Din Tai Fung in Taipei in 1972. Over the last four decades, Din Tai Fung has become a vast global franchise, with more than 100 restaurants in twelve countries and territories. The company declared “Din Tai Fung’s xiaolongbao has become the symbol of Taipei!,” causing outrage across the Taiwan Strait in Nanxiang and Shanghai. Din Tai Fung might have made xiaolongbao famous worldwide, but for Shanghai’s gourmands, it’s sacrilege to admit you like Taiwanese xiaolongbao. “Too expensive,” “Too touristy,” and “Not Shanghainese” they pout. But the restaurant prides itself on an almost scientific approach to making xiaolongbao, every dumpling having exactly 18 lucky pleats and weighing between .73 and .74 ounces. That’s a margin of error the weight of a corn kernel. “Such scientific precision is what makes Din Tai Fung stand out from the rest,” says Yang Jihua, son of founder Yang Bingyi.

Few things get the Shanghainese as riled up as the question of xiaolongbao’s provenance, which speaks of a larger, deeper rift between mainland China and Taiwan. At the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, Mao Zedong’s victorious communists took power and the battered nationalists opposing them fled to Taiwan. Mao claimed Taiwan as part of the People’s Republic of China, although Taiwan certainly didn’t see it that way. The relationship between China and Taiwan has been testy ever since. It's personal too. Those in Shanghai see the Taiwanese as weak and pampered—after all, they didn't suffer through the cultural revolution—and the Taiwanese, in turn, consider those from Shanghai to be uncultured money-grubbers, blinded by communism. I met a delightfully polite man from Taipei once on a boat. We chatted about about travel and literature, but when I told him I lived in Shanghai, he looked at me with true compassion. “They’re so backward in Shanghai—all they care about is business and money, money, money,” he said. “Ironic, isn’t it? Given that they’re communists.”

But Mavis Tseng, a food-obsessed, 25-year-old Taiwanese, tries to see both sides of the argument. “The reality is that both China and Taiwan share culture and history.”

Now that Shanghai has become a sophisticated world city in its own right, rivaling, and some would say, eclipsing Taipei, Shanghai is claiming their culinary heritage back. “Shanghai owns xiaolongbao, and its birthplace is Nanxiang town in Jia Ding district,” insisted Shen Mingyu, my Shanghainese friend and the most passionate foodie I’ve ever met, anywhere in the world. “I will fight for xiaolongbao’s birthplace,” he told me, squaring his shoulders, as though a legion of Taiwanese xiaolongbao cooks was, at that moment, readying to march on Shanghai. The original Shanghai Nanxiang Steamed Bun restaurant chain has planned its own invasion into South Korea, Japan, and Singapore. But not Taiwan—not yet.

But when I asked Gwen Lin, another friend’s wise, old Taiwanese mother-in-law, where she thinks xiaolongbao originated, she struck a peace deal for the warring factions. “Originally China,” she said, after a long pause. “But you cannot deny that xiaolongbao tastes great in Taiwan.”

Self reflection.Photo credit

Self reflection.Photo credit  Older woman touching hands with a younger self.Photo credit

Older woman touching hands with a younger self.Photo credit  Sign reads, "Regrets Behind You."Photo credit

Sign reads, "Regrets Behind You."Photo credit

Couple talking in the woods.

Couple talking in the woods. Woman and man have a conversation.

Woman and man have a conversation. A chat on the couch.

A chat on the couch. Two people high-five working out.

Two people high-five working out. Movie scene from Night at the Roxbury.

Movie scene from Night at the Roxbury.  Friends laughing together.

Friends laughing together.

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/

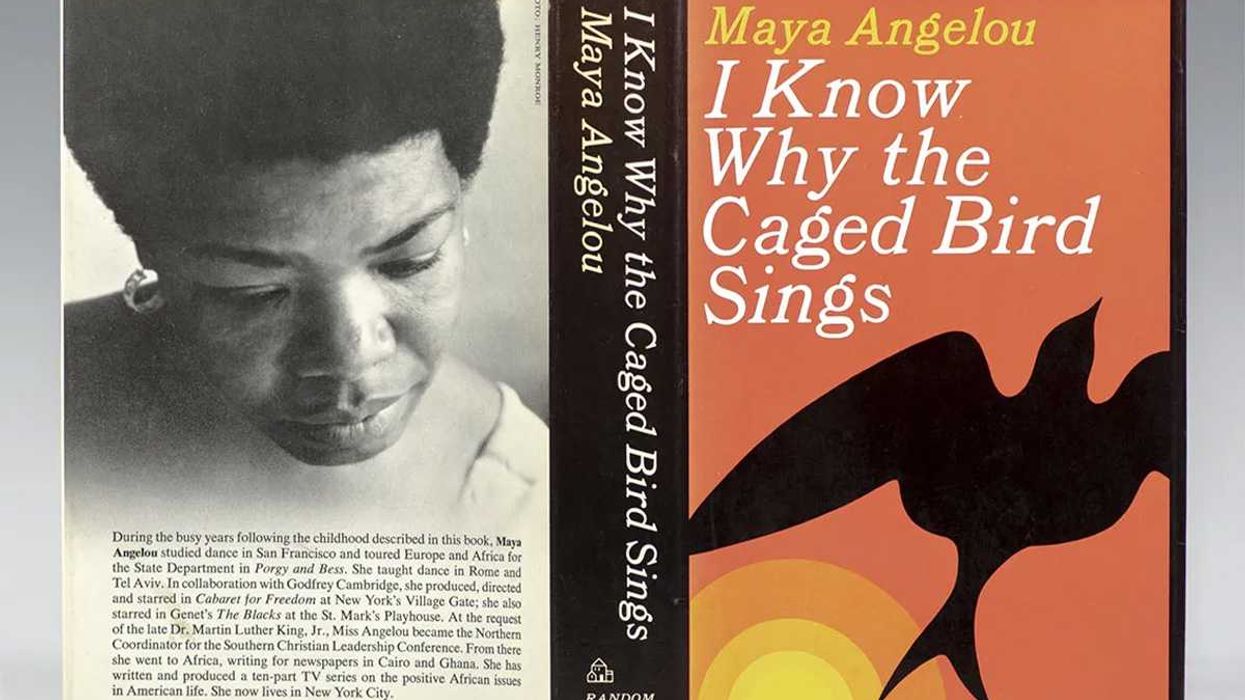

Maya Angelou reciting her poem "On the Pulse of Morning" at President Bill Clinton's inauguration in 1993.William J. Clinton Presidential Library/  First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

First edition front and back covers and spine of "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings."Raptis Rare Books/

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva

Tow truck towing a car in its bedCanva  Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva

Sad woman looks at her phoneCanva  A group of young people at a house partyCanva

A group of young people at a house partyCanva  Fed-up woman gif

Fed-up woman gif Police show up at a house party

Police show up at a house party

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva

A trendy restaurant in the middle of the dayCanva A reserved table at a restaurantCanva

A reserved table at a restaurantCanva Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

Gif of Tim Robinson asking "What?' via

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva

An octopus floating in the oceanCanva