Looking back in a decade or two, we might well remember 2010 as the year that the weather got really wacky. Or, perhaps, as the year that the effects of long term global climate change started to really tweak short term weather patterns.

One thing is clear: this was a wild, violent, and catastrophic year in extreme weather events.

Don't trust a layman like me. Weather Underground's founding meteorologist Jeff Masters said, "In my 30 plus years of being a meteorologist I can't ever recall a year like this one as far as extreme weather events go, not only for U.S. but the world at large."

Now let's be clear: no single weather event is evidence alone of climate change. But it's also true that most, if not all, of the extreme weather events of 2010 do fit within the predictions of climatic extremes that the best science is warning us of in the coming century.

Kevin Trenberth of the Nation Center for Atmospheric Research offers this take:

We can't attribute a single event to climate change, but I would contend that every event has a climate change component to it nowadays. And a different way of thinking about it is try to look at odds of that event happening. And, with some of the events that we've had this year it's clear—even though the research has not been done in detail yet—that the odds have changed, and we can probably say some of these would not have happened without global warming, without the human influence on climate."

Trenberth hints at a common metaphor used in climate science circles: that global warming is "loading the dice" for extreme weather patterns. One climate scientist, Steven Sherwood, carries the metaphor a bit further, writing to Andy Revkin at Dot Earth:

Climate change also allows unprecedented (in human history) things to happen. It is more like painting an extra spot on each face of one of the dice, so that it goes from 2 to 7 instead of 1 to 6. This increases the odds of rolling 11 or 12, but also makes it possible to roll 13. What happens then? Since we have never had to cope with 13’s, this could prove far worse than simply loading the dice toward more 11’s and 12’s.

You can decide for yourself whether the extreme, destructive events of 2010—the Russian heat wave or the floods in Pakistan or the Amazon's drought—count as 12's or 13's. You can't argue that it's been a wild year for weather.

Kids on their computers.Photo credit:

Kids on their computers.Photo credit:  Young girl holds a drone.Photo credit

Young girl holds a drone.Photo credit  Playing with bubbles.Photo credit:

Playing with bubbles.Photo credit:  Friends on the computer.Photo credit:

Friends on the computer.Photo credit:

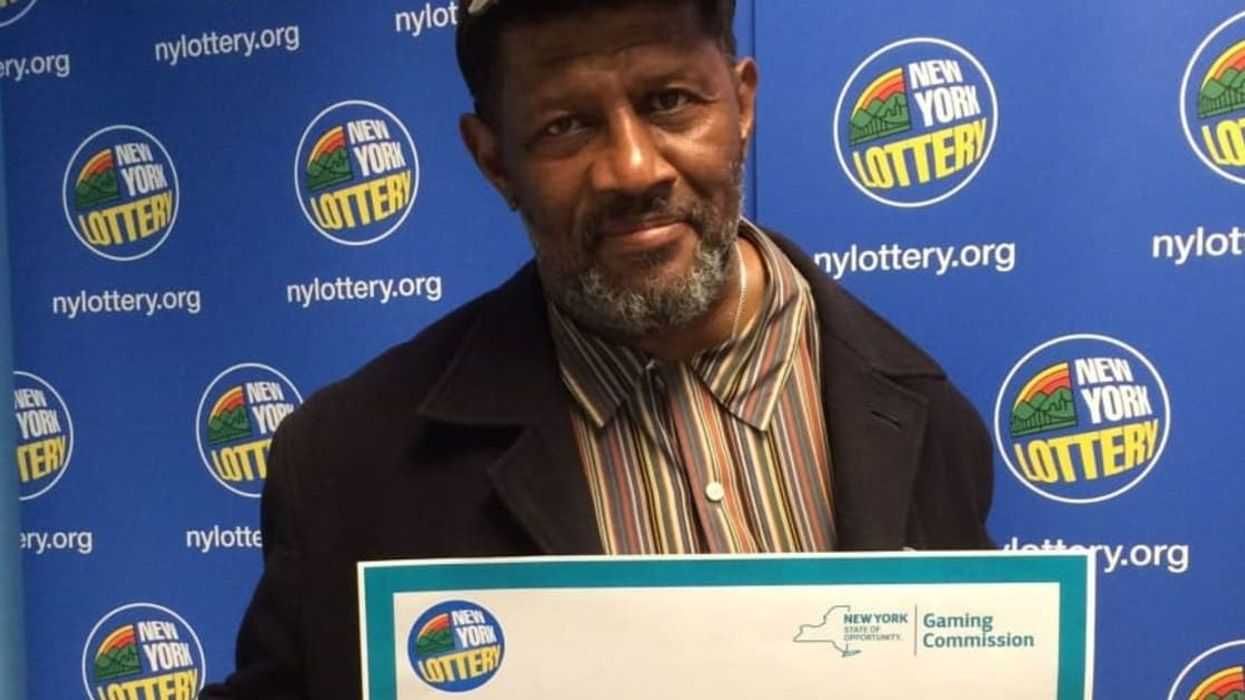

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |

Screenshots of the man talking to the camera and with his momTikTok |  Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

Screenshots of the bakery Image Source: TikTok |

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva

A woman hands out food to a homeless personCanva A female artist in her studioCanva

A female artist in her studioCanva A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva

A woman smiling in front of her computerCanva  A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva

A woman holds a cup of coffee while looking outside her windowCanva  A woman flexes her bicepCanva

A woman flexes her bicepCanva  A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva

A woman cooking in her kitchenCanva  Two women console each otherCanva

Two women console each otherCanva  Two women talking to each otherCanva

Two women talking to each otherCanva  Two people having a lively conversationCanva

Two people having a lively conversationCanva  Two women embrace in a hugCanva

Two women embrace in a hugCanva

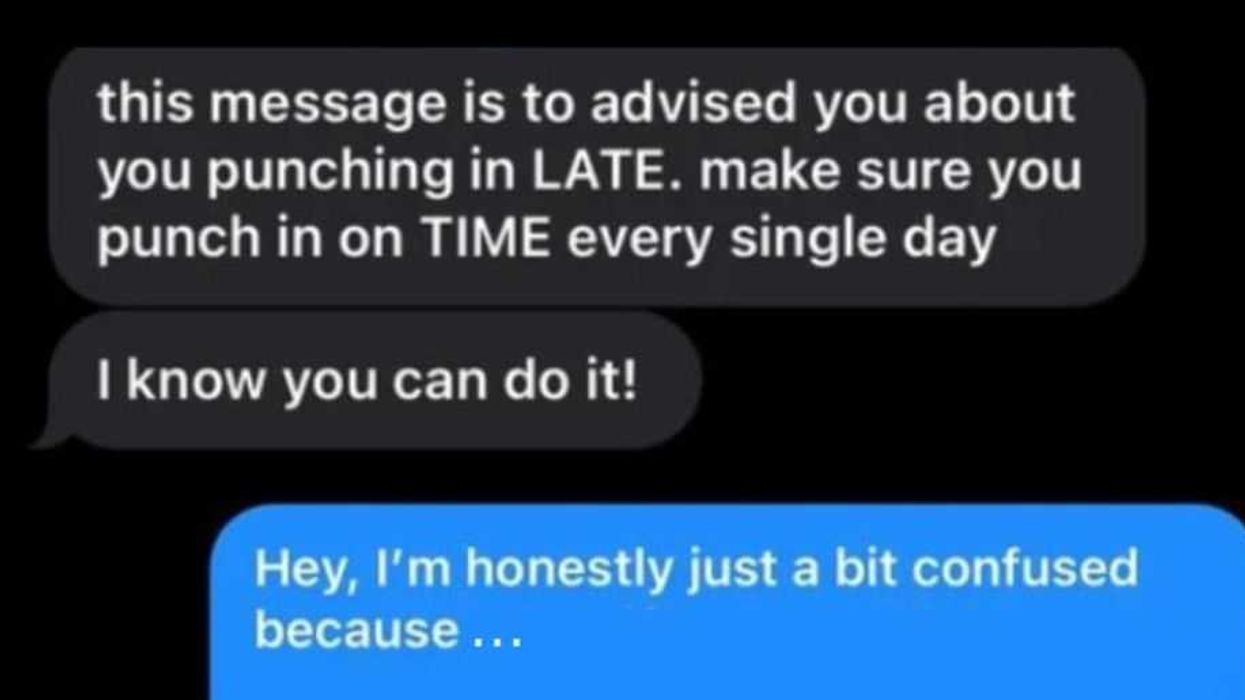

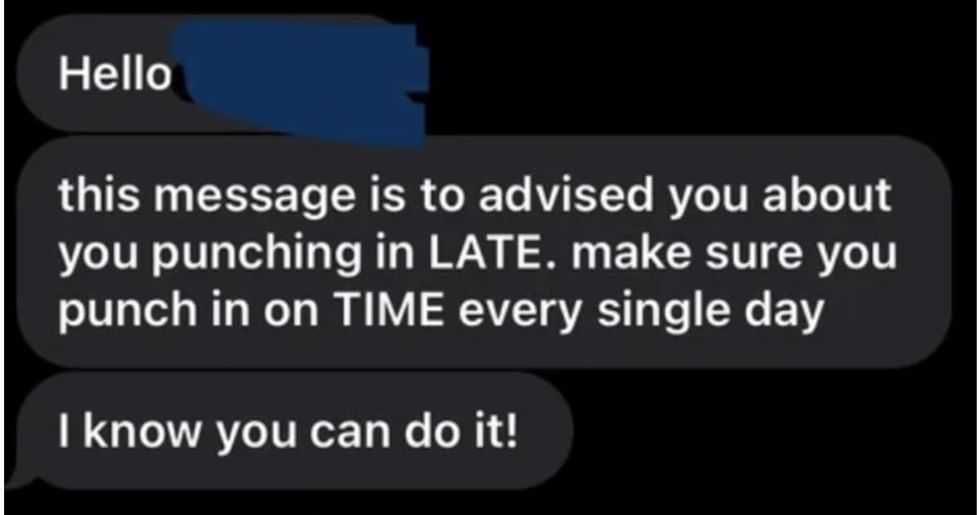

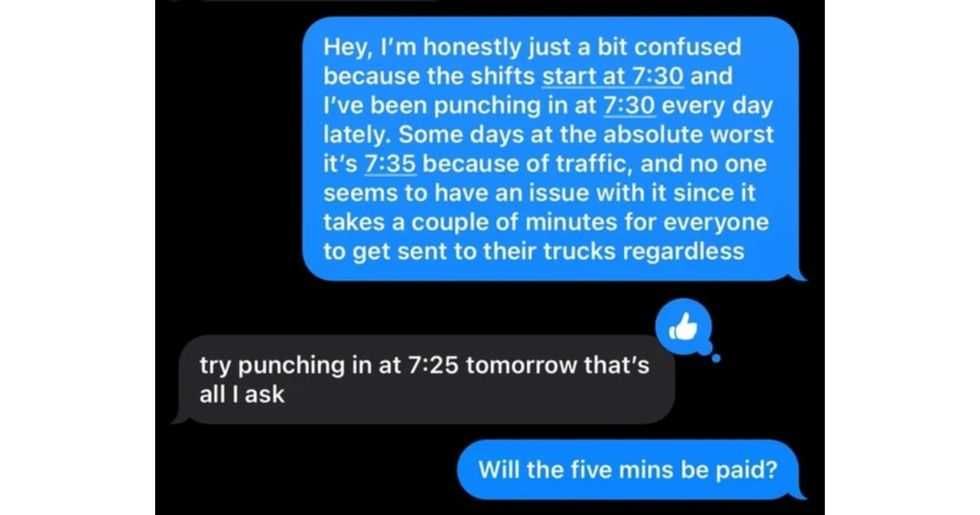

A reddit commentReddit |

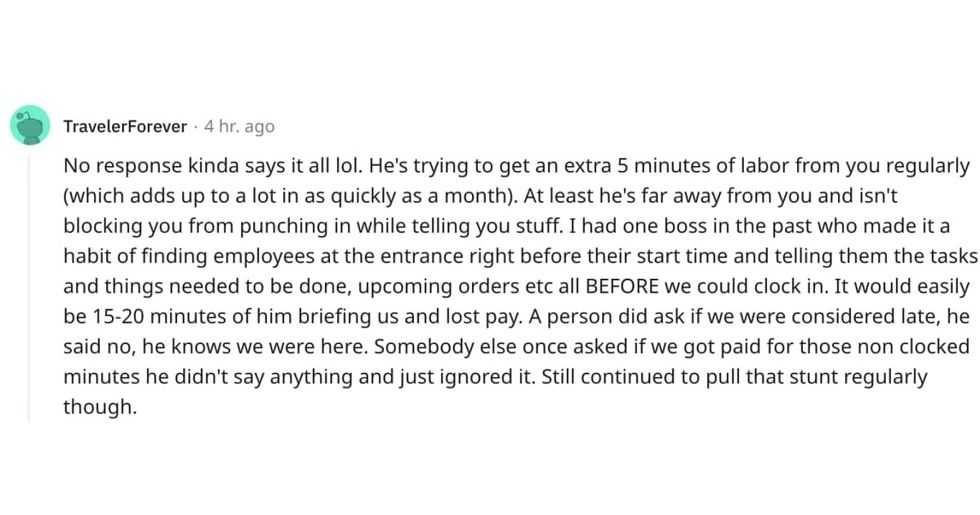

A reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  A Reddit commentReddit |

A Reddit commentReddit |  Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Stressed-out employee stares at their computerCanva

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Who knows what adventures the bottle had before being discovered.

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via

Gif of young girl looking at someone suspiciously via