We here at GOOD Sports have spent December focusing on women’s sports, largely as a counter to the disproportionate amount of coverage men’s sports receives. It’s not difficult to understand how the inequity became reality, but it can be frustrating to see how slowly that reality is changing, if at all. Of course, when it comes to experiencing women playing sports at a high level in front of a passionate fan base and with extensive media coverage, maybe I’m spoiled. After all, I’m from Storrs, Connecticut.

In my home state, there’s something called Huskymania. It describes the fervor around UConn basketball, for which the state’s sports fans are arguably more passionate than they are about any other team. Sure, the Yankees and Red Sox, the Pats and Giants, the Celtics—they all receive plenty of love, but it pales in comparison to the attention and media coverage given to Husky hoops. The program is Connecticut’s own—even more so since the NHL’s Hartford Whalers left the state nearly 20 years ago.

Over the past 17 years, the UConn men’s team has been one of the most successful in college basketball, winning four national championships during that span. And that doesn’t even compare to what the women’s team has done.

Eleven NCAA titles in that same timeframe. A current win streak of 87 games. Past win streaks of 90 and 70 games. Five No. 1 WNBA draft picks, and the top three picks in the 2016 draft.

This is one of the most successful programs—with some of women’s basketball’s biggest stars—in women’s sports history.

I grew up about a mile from Gampel Pavilion (and before that, the Field House), the on-campus home of University of Connecticut basketball. The men’s team won the second-tier National Invitation Tournament in 1988, and two years later—when Gampel opened—they won the Big East and reached the NCAA Tournament Elite 8 on a spectacular last-second shot before falling a buzzer-beater short of reaching the Final Four. The fan and media frenzy (the press contingent following UConn was nicknamed “The Horde”) crescendoed, and Connecticut’s Huskymania was born.

The women’s team, meanwhile, was also finding more and more success, winning some conference titles and making a surprise run to the Final Four in 1991. And while interest and attendance was growing, in the early days of Gampel, my high school friends and I still could get tickets at the door and sit a row or two behind the basket. The women’s games were enjoyable, but not necessarily a “big deal.” Still, all women’s games not on standard cable could be watched on Connecticut Public Television, allowing further growth of fan base.

It didn’t match the men’s program’s popularity, but that was about to change.

In 1995, UConn started an annual game with Tennessee, which sold out in advance. The biggest powerhouse in women’s basketball, led by legendary coach Pat Summitt, visiting the undefeated, upstart Huskies. The game aired on ESPN. The Associated Press delayed its weekly poll to determine which team should be No. 1., and UConn won, becoming the nation’s top-ranked team—not losing the rest of the season and claiming its first title with another victory over Tennessee, no less.

Regularly from then on, the crowds were big—and discernibly higher-pitched than the men’s crowds. There was a large fan base overlap between the two teams, though they weren’t exactly the same group. The women’s games also featured a bit less caustic fan rancor—as one commonly hears at men’s sporting events—toward opposing players. Until UConn-Tennessee, 1999 edition, that is.

The game was televised on CBS. Tickets were being scalped for $200. UConn’s Svetlana Abrosimova and Tennessee’s Semeka Randall tangled for a loose ball, with Randall allegedly sneaking in a cheap shot (though the reality is unclear). Abrosimova was furious, as were the fans, who mercilessly booed Randall for the rest of the game.

And more sports fans were exposed to the intensity at the top levels of women’s basketball.

The following year’s matchup became the first women’s basketball game to be televised live in prime time (ESPN). And fans kept showing up and tuning in.

Fast forward to last season, and Division I women’s basketball attendance was 8,286,356, marking the highest total in the 35 years of NCAA women’s basketball. Sure, there are concerns about UConn’s dominance impacting ratings, as well as whether it’s good for the sport. But fans are attending games in record numbers. Women’s basketball is holding its own.

In 2004 and again in 2014, both the Connecticut men’s and women’s teams won national championships, marking the only two times that has ever been done by the same school in the same year. And UConn, which begins each season with a scrimmage involving both teams playing a co-ed game, honored the men and women with a joint rally/parade. The 2004 celebration brought in 300,000 people, while the 2014 edition drew 200,000 to downtown Hartford. When the men—but not the women—won the championship in 2011, the parade crowd was about 40,000.

This isn’t to say the programs themselves are perfect. The men have run afoul of NCAA regulations on a couple of occasions, and women’s coach Geno Auriemma’s recruiting tactics have come into question now and then. But these types of issues are common—for better or worse—in college basketball, and that’s not even the point.

It’s that within this market, in this sport, the men’s and women’s teams are viewed on equal footing. Other schools have top-notch, championship-caliber teams that draw crowds and ratings in both sports as well, including Notre Dame, Maryland, and Louisville, just to name a few.

The U.S. Women’s soccer team is viewed the same way—at least by fans. They are fighting for that to be reflected in paychecks, marketing, and support, as well. You can market the hell out of a bad product and probably see some bump, but it’s not sustainable. But when all the ingredients are there—a great team, a fan base, marketing, media exposure—there’s no reason the fans won’t follow. Which creates more media interest, which bolsters fan interest, and so on and so forth.

ESPN networks were set to broadcast 66 NCAA women’s basketball games this year (more if you include their conference affiliate networks), plus the conference tournaments, and the entire NCAA tournament. Of course, that pales in comparison to the hundreds of men’s games ESPN televises, but once upon a time the fledgling network partnered with the fledgling Big East conference to televise men’s games, and the relationship grew from there and greatly benefited both.

Now ESPN and men’s college basketball are big business with die-hard fan bases.

In other words, for many women’s sports, there’s a long way to go. But this kind of growth has been achieved before. And with the UConns and Notre Dames and Baylors and Tennessees leading the way, it can be done again.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/

Leonard Cohen performs in Australia in 2009.Stefan Karpiniec/  Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

Enjoying a sunset.Photo credit

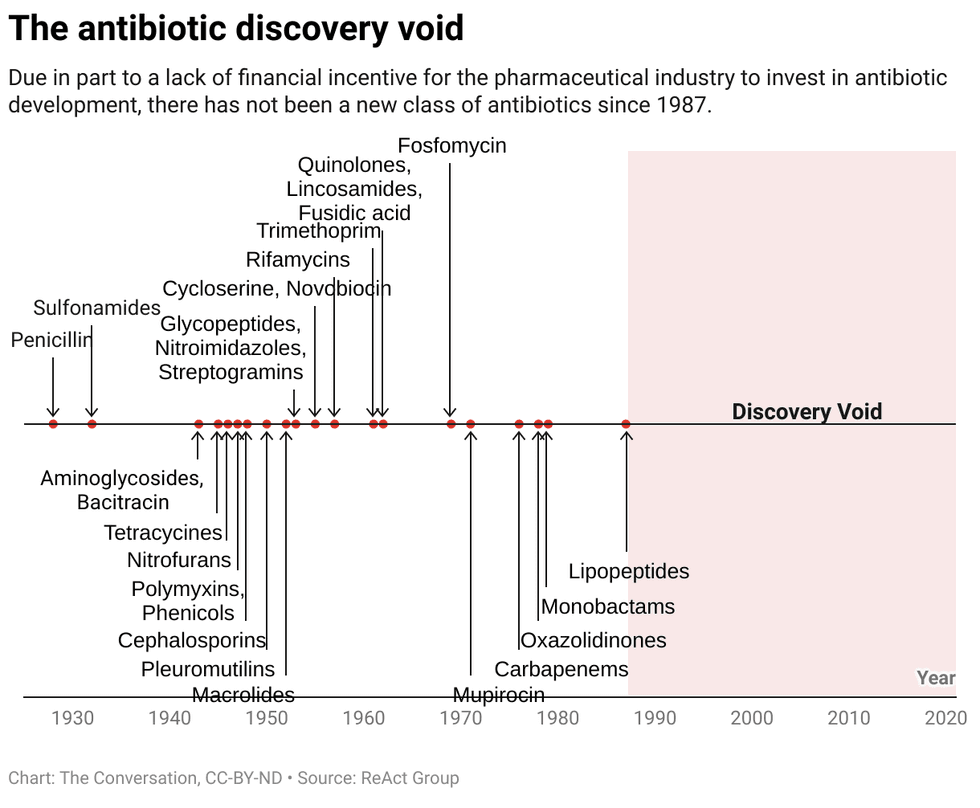

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

An envelope filled with cashCanva

An envelope filled with cashCanva Gif of someone saying "Oh, you

Gif of someone saying "Oh, you