Hitler, despite suffering from chronic flatulence, was a vegetarian and in pretty good health at the time he orchestrated the slaughter of millions of innocent people. Romanian dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu was a nonsmoker and cardio enthusiast when he launched mass murdering sprees of his own. Surely, there are modern misogynists who can run a six-minute mile and Islamophobes with low body fat percentages. But should we consider a person healthy if he or she nurtures feelings of intense hatred? UCLA Medical Professor Dr. Robert H. Brook doesn’t think so.

This past Valentine’s Day, Brook addressed the insidious role hate plays in health, arguing in a JAMA article that medical professionals should play a larger role in combatting intolerance. Brook, who is also a Distinguished Chair in Health Care Services at the RAND Corporation, believes medical professionals have a responsibility to reduce intolerance, along with the necessary widespread respect to make a real difference.

“It is time to expand the WHO’s definition of health to include acceptance and tolerance,” Brook writes, “No community or nation should be considered healthy if hatred is pervasive. Nor should any individual be considered healthy if he or she is intolerant.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]No community or nation should be considered healthy if hatred is pervasive.[/quote]

What may seem like a radical idea at first glance actually falls in line with medicine’s broadening scope. When Brook got his start in the medical field in the 1960s, most people viewed doctors as fixers of broken bones and nemeses of pneumonia. Fast-forward half a century, and doctors ask patients about loneliness as routinely as they take temperatures. In a relatively brief span of time, medicine has evolved to encompass preventative care, while also recognizing the complex factors that can influence an individual’s health.

There’s no time like the present

“Now that Trump is president, I’m going to shoot you and all the blacks I can find.” That’s what one 12-year-old black student had the misfortune of hearing from a classmate the day after Donald Trump won the presidency. Sadly, her experience was just one of nearly 900 hate-fueled incidents reported to the Southern Poverty Law Center in the first 10 days following Trump’s election night win. It’s been three months since that initial surge and instances of hate speech have yet to return to pre-election levels.

Clearly, America has a problem with hatred. Rethinking how we measure and improve national health will be necessary if the United States hopes to keep up with other developed countries. A recent study led by Imperial College London scientists and the World Health Organization showed that Americans are falling behind when it comes to improving average life expectancy. In fact, researchers expect the United States to see some of the smallest lifespan gains compared to those of other high-income countries. The study’s writers fault the United State’s lack of universal health care, high maternal death rates, and obesity for our stagnant life spans. But what if prejudice also plays a role?

There’s plenty of evidence to support the idea that anger can negatively affect your health. But bearing the weight of toxic emotions barely scratches the surface of intolerance’s destructive (and typically unchecked) reach. In his article, Brook offers up a few eerily relevant examples of why this is a problem. For instance, a doctor might examine a woman and deem her perfectly healthy, only to hear about her shooting dozens of people weeks later. Which begs the question, what if Omar Mateen had communicated with his general physician a desire to harm gay people? Or if Dylann Roof had mentioned his hatred of black people during an annual checkup? Currently, there is no standardized training for handling intolerance among patients.

Brook believes adding just a few questions to a routine medical exam could help ignite a discussion about intolerance and potentially prevent terror attacks as a result. Clinical psychologist Dr. Sonja Raciti agrees, suggesting doctors ask patients if they feel safe within their communities, families, and relationships, as well as asking if they regularly feel angry. She explains that, while doctors have a limited amount of time to interact with their patients, “a quick question measuring anger/hatred would allow both physicians and mental health practitioners to focus briefly on intolerance.” From there, patients identified as intolerant could be referred to specialists in the same way practitioners refer depressed patients to qualified psychiatrists. Even if patients lie about their feelings, asking the question reaffirms the potentially life-threatening consequences of intolerant behavior.

How do we treat it?

Brook says the first step would be to find a way to measure intolerance accurately and quickly. From there, researchers would need to start testing interventions that might work. Only after years of dedicated research could the American Psychiatric Association consider adding intolerance to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Originally published in 1952, the manual has been updated a total of five times with the most recent update published in 2013. Among the 15 disorders added to the list, caffeine withdrawal syndrome and hoarding disorder stirred up some controversy for supposedly diluting the significance of a clinical disorder. Undoubtedly, intolerance would ruffle feathers as well.

While Brook doesn’t specifically mention the DSM-5 in his article, Raciti says it’s a necessary part of successfully treating psychiatric disorders. Though that doesn’t mean the APA always gets it right. Raciti tells GOOD,

“There are certain instances where the DSM-5 has failed to include diagnoses which clinicians see on a routine basis. A good example for this: Only gambling addiction is included in the DSM-5 as a process addiction. However, sex, gaming, internet, and food addictions are widely recognized by a majority of addiction experts and treatment facilities … The difficulty then lies with billing for a disorder without having the appropriate DSM-5 code.”

She adds that politically sensitive conditions face additional scrutiny. By that measure, we can safely assume intolerance won’t be officially recognized any time soon.

In the meantime, Brook says one very simple strategy might involve placing signs at health facilities informing patients that intolerance impedes optimal health, but trained professionals are available to discuss more. The idea is simple, but it could have profound implications we have yet to discover. What we do know is that doctors have a unique opportunity as highly respected authority figures to influence their patients and the general populace for the better.

Looking ahead

A few decades from now, Brook hopes treating intolerance will seem as obvious as treating depression or anxiety. And while doctors may not be able to root out intolerance entirely, they could affect enough people to trigger a seismic shift. As Brook notes, the flu vaccine only works about half of the time (according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention), but doctors continue advising everyone to get the shot each fall. “We won’t succeed with everybody,” says Brook, “but we may succeed with enough. We may move the needle enough that the world becomes a much more pleasant place in which to live.”

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]We really do need a world in which ... we don’t go around killing each other because people are different from us.[/quote]

While there are obvious complexities associated with intolerance and countless challenges for those trying to eradicate it, Brook says we shouldn’t let that deter us. He predicts the medical profession could potentially have a bigger impact on global health by focusing on intolerance as opposed to more conventional, chronic diseases. “Even though we’ve got to solve those problems as well,” he explains, “we really do need a world in which, when we solve all those problems, we don’t go around killing each other because people are different from us.” Put this way, the case for diagnosing intolerance becomes inordinately simple. Technological advances, whether they eliminate disease or extend our lives by hundreds of years, still won’t protect us from the threat we pose to ourselves.

So far, Brook says the response to his article has been mixed. While some have expressed excitement at the thought of expanding physicians’ roles, others would rather see doctors stick to curing pneumonia and fixing broken bones. But the detractors won’t stop him from advocating for change in the medical profession. “It could be a fantasy or it could be something that actually will work,” he says, “but we have to try something.”

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

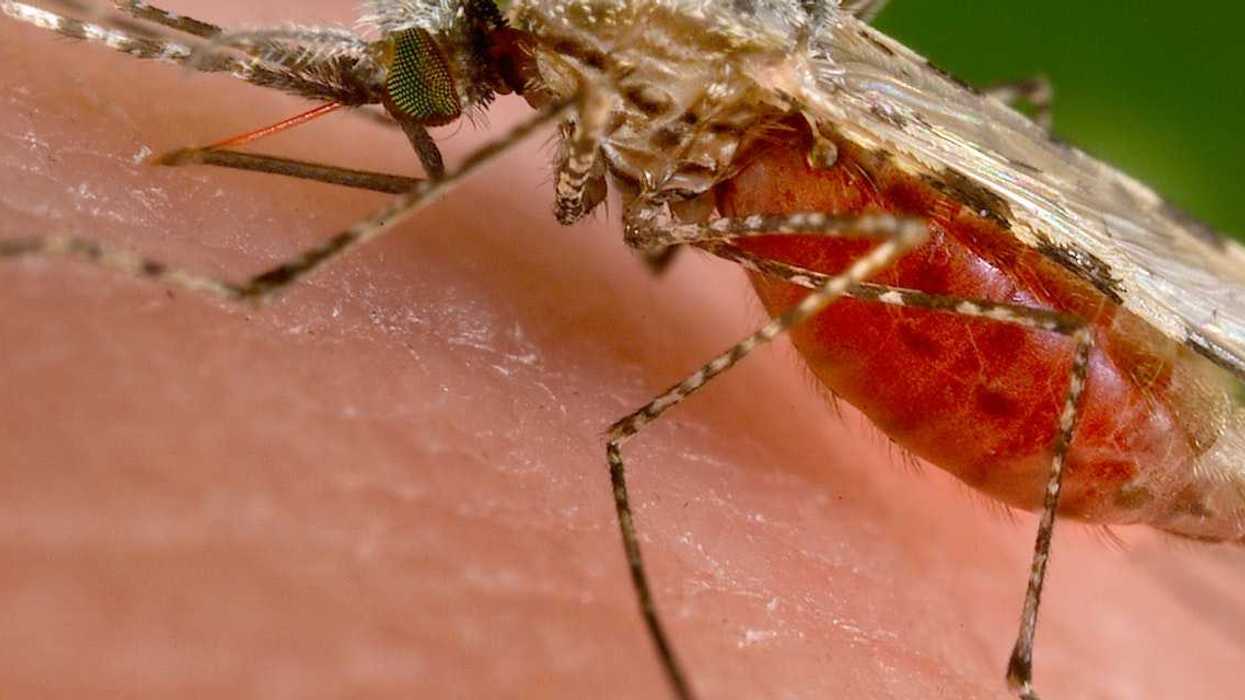

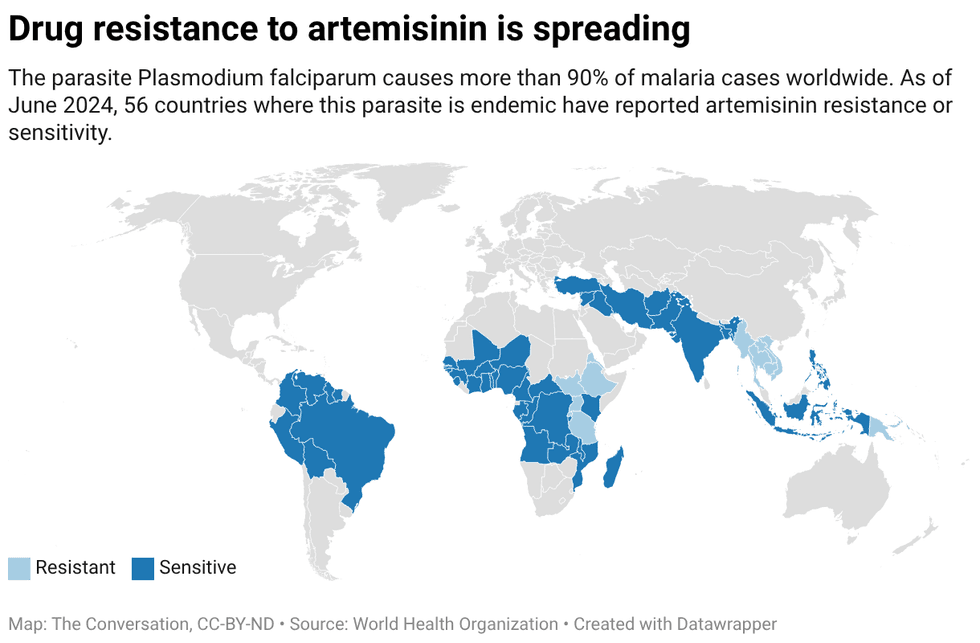

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

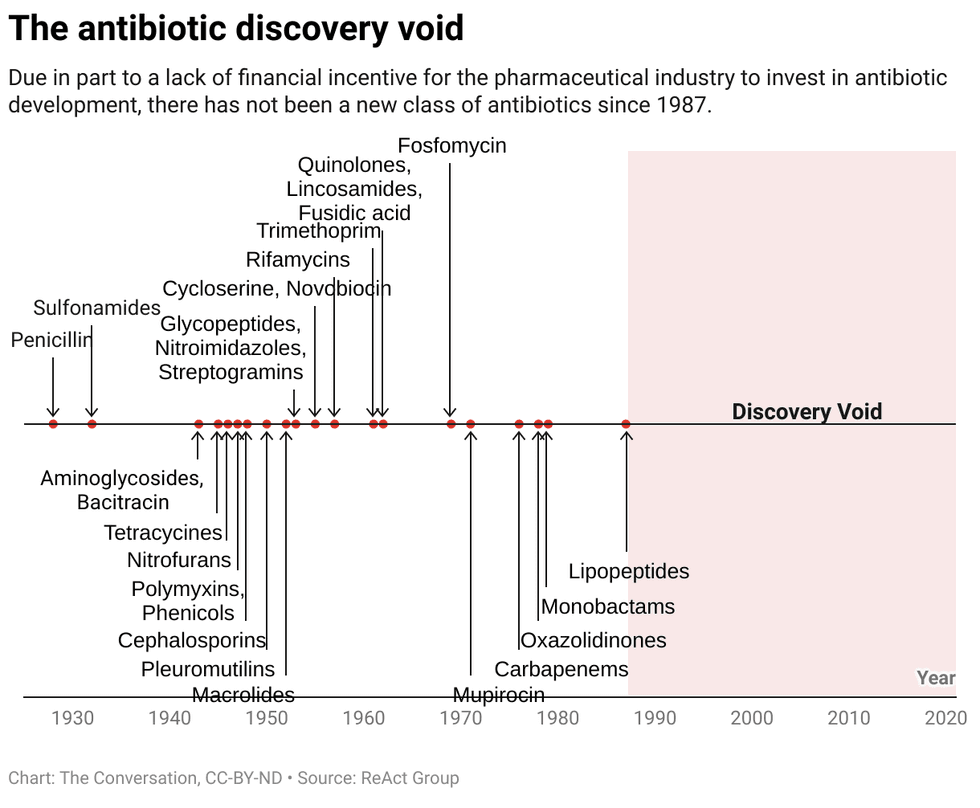

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.