In 1988, Tucson, Arizona-based astronomers David Crawford and Tim Hunter became concerned that the night sky above their heads was getting too bright. The city lights certainly posed a professional threat—obscuring the stars and galaxies that had become their livelihoods. But even more troubling to the duo was that increased economic development in urban areas (construction sites, downtown strips, shopping malls, restaurants) appeared to be having unusual effects on human health, as well as on urban wildlife populations. Migratory bird species, for instance, were often driven off course by billboards or skyscrapers with a neon glow.

So Crawford and Hunter founded the International Dark Sky Association, or IDSA, a network of astronomers and other scientists, along with volunteers, bent on preserving the sanctity of light pollution-free, star-filled night skies. Today, the group numbers around 3,000 members spread over 50 countries. IDSA program manager John Barentine says that the organization’s goal is not to turn off all the world’s lights, but rather to improve the quality of outdoor lighting.

Barentine believes 2017 could be the turning point for the revolution in how cities are lit, given that the American Medical Association recently acknowledged that cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity as at least partial products of chronic sleep disruption brought on by exposure to bright light sources at night. To help solve this problem, IDSA’s grassroots campaigning and publicity-generating “star parties” call for towns and cities to implement “warmer” municipal lighting systems—as opposed to the harsh, yet traditional, short-wavelength “blue” light.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Giving the right light to people during the day may be just as important as removing it at night.[/quote]

But Dr. Steven Lockley at the Harvard Medical School isn’t convinced. He studies the connection between light exposure and human health, and argues that while street lights “aren’t equivalent to darkness,” the outside glare still isn’t strong enough to penetrate into people’s bedrooms. The real sleep cycle disruptors, he argues, are indoor electric light sources, like TVs, tablets, and laptop screens.

A 2015 study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences confirmed that exposure to an e-book before bed “acutely suppresses melatonin.” This is one of the central complaints around after-dark exposure to artificial light. Here’s why: Melatonin, a neurohormone that regulates our sleep and wake patterns, is vital to our basic functioning as humans. Eating, walking, talking—even just staying alert through the day—all depend on whether you’ve received enough melatonin during the night.

Less melatonin means less deep sleep, and “less deep sleep means less recovery and more sleepiness upon waking,” says Lockley. As an example, he cites young children, who require deep, slow-wave sleep to produce growth hormone (which in turn affects brain and body development). “Any light between dusk and bedtime will likely have a biological effect, but by minimizing the intensity and blue-light content, you can minimize these effects on sleep.”

But as it turns out, giving the right light to people during the day may be just as important as removing it at night.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]I remember walking around the department store during Christmas and just crying for no reason. [/quote]

“During winter, there’s a greater duration of melatonin,” explains Dr. Alfred Lewy, one of the pioneering researchers of light therapy. The method was first attempted in 1982 as a way to treat seasonal affective disorder, a term coined two years later by fellow psychiatrist Norman Rosenthal.

As Lewy explains, patients with SAD experience a “drift,” or lag, in their internal body clock, due to the slow onset of dawn in winter. “Our clock is cued to that first bright light exposure in the morning when we wake up; it resets our 24-hour rhythm.” As a result, he concluded that people with SAD needed bright light exposure in the morning to reset their clock.

Oklahoma-raised Sherrie Baxter never had an issue with seasonal affective disorder, until she moved to Oregon in 1991. “I remember walking around the department store during Christmas and just crying for no reason. And then spring would come, and I’d go back to normal and forget all about it.” When her mother spotted an ad in the local newspaper by the Oregon Health and Science University, Baxter ended up enrolling as a research subject for light therapy, and she says the experience—which involved being exposed to a box-like contraption that emitted bright beams of white light at designated times during the day—made “a huge difference.”

In fact, she felt so much better, she became a missionary for light therapy, spreading the gospel as much as possible to her community in Portland, where up to 15 percent of the population suffers from SAD. She even tried getting a few light boxes for her sister and friends. But at $1,000 a piece, they were too expensive for most. So, with help from researchers at OHSU, she decided to build her own line of user-friendly, cost-effective light boxes.

Her efforts paid off: Today, Bio-Light light boxes are shipped all over the world and recommended by doctors who work in the field; they’re even used at light therapy research centers (which is ironic, given Baxter’s history as a former research subject). Each set comes with a chart explaining how much brightness you’ll receive depending on your distance from the box. For example, if you’re 44 inches away, then the brightness level is 2,500 lux, which is the amount needed to turn off melatonin.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Any light between dusk and bedtime will likely have a biological effect.[/quote]

“You don’t stare at the light, you just keep your eyes open,” Baxter explains, “That way, it goes through your retina and gets transmitted to the brain.”

Traditionally, the function of light therapy has been limited to winter mood-boosting—but that’s changing. “The original research was on SAD,” Baxter explains, “but in the last several years, they discovered it’s more complicated than that.” She points to researchers in San Diego, who in 2015 found that exposure to light lessened depression, regardless of the season. Similar results were found in studies done on women experiencing premenstrual syndrome. And just last month, the BBC reported that light therapy is even being tested to fight the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Baxter adds: “We’ve also sold a lot of units to veterans, for regular depression, but also for post-traumatic stress.”

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Light therapy is being tested to fight the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease.”[/quote]

Meanwhile, in Australia, researchers at the Monash Institute of Cognitive and Clinical Neurosciences—which has its own sleep program—have experimented with blue light therapy as a way to treat patients with brain injuries. And perhaps most amazing of all: A team in Europe is declaring that men with low libido experienced a near double boost to their testosterone levels after exposure to light.

All of which may, in a very roundabout way, help to underscore John Barentine’s original point, and the larger mission of IDSA. “We want people to think differently about their relationship to light,” he says. “If they can change their view of what quality lighting is, they’re going to naturally gravitate toward feeling like they need less of it.” And that’s a good thing—whether people want to see more of the Milky Way, or simply become more proactive about their own health.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

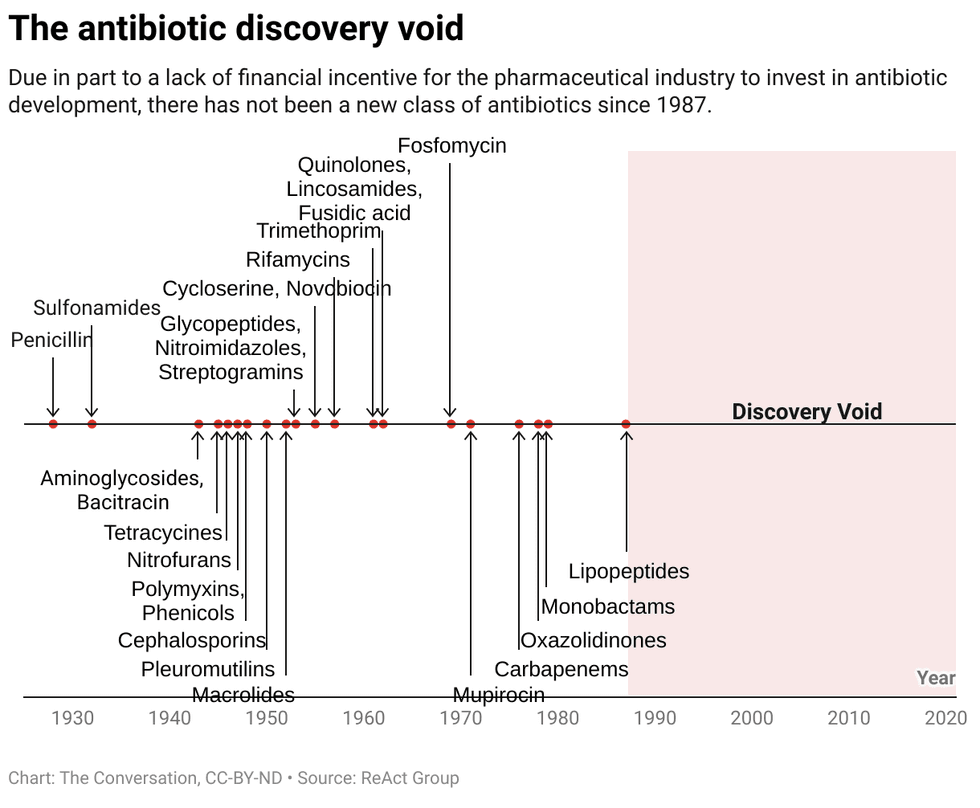

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:  Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:

Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:  Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit:

Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit: