Throw around the word “opioid”—a morphine-derived painkiller like heroin, Vicodin, or Oxycontin—and “epidemic” is likely to follow. The Centers for Disease Control estimates that U.S. deaths from opioid abuse are at a record high, with 78 fatalities occurring every day, a number that has quadrupled since 1999. A 2016 Kaiser Health survey found that nearly half of respondents reported knowing someone with an addiction to heroin, which in certain parts of the country is becoming a cheap, easily accessible alternative once the prescription runs out.

Congress has responded by authorizing $181 million in state grants for substance abuse treatment centers, while President Obama has made anti-addiction drugs more available. Yet the root cause remains largely unaddressed: People keep overdosing on opioids because they’re as incredibly effective—and dangerously addictive—as ever.

But help appears to be on the way, thanks to scientists across four institutions—UC San Francisco, Stanford University, the University of North Carolina, and the Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nurnberg in Germany—who’ve developed a compound from scratch that kills pain just as effectively as opioids, though it has entirely different characteristics.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]If you use opiates you get to kiss God. So your brain starts telling you to go do it again.[/quote]

The four-year effort was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Rather than beginning as many studies on drug candidates do—by dissecting the molecular structure of a certain compound—the researchers began by looking at the brain. Specifically, the opioid receptor in the brain, which activates a signal in the dopamine circuit.

Brian Shoichet, PhD, a professor of pharmaceutical chemistry in UCSF’s School of Pharmacy and co-senior author on the paper, which was published last month in Nature, calls this “the happiness circuit, involved in a lot of types of addiction,” from nicotine to gambling and, yes, opioid addiction.

As described by Ivan Hodes of Alaska Commons:

The point of the signal is to make you remember that whatever you did felt good, so that you do it again the next time you have the opportunity. [When you take opioids, the] brain releases just gigantic amounts of dopamine, far more than are released by endorphins, and so you feel pleasure, euphoria, like you’ve never felt before (Lenny Bruce once described it as “like kissing God”).

Now your brain has learned something: If you use opiates you get to kiss God. So your brain starts telling you to go do it again, just begging you.

The key was to find a molecule that would bind well with that opioid receptor without affecting dopamine levels. Building on previous findings and using computational modeling, “We screened three trillion molecules, winnowed that down to twenty-three, and we went from there,” says Shoichet.

Eventually, the researchers were able to isolate a single molecule called PZM21.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]There’s an American cultural phenomenon that goes with taking a pill, to have no symptoms at all and function at your highest level.[/quote]

“The chemical structure of this molecule is very different from opioids,” Shoichet says, and does not activate the dopamine circuit in mice, which the team tested for signs of addiction. Years later, those signs simply aren’t there. The mice didn’t experience a slowdown in breathing either, which is a major contributor to opioid-related deaths.

“Like morphine, this molecule binds to the mu-opioid receptor,” Shoichet explains, but unlike morphine, PZM21 doesn’t activate the neural pathway that leads to side effects like depressed respiration and constipation.

The drug is a big step toward ending our national addiction to prescription narcotics, which likely kicked off in the late 1980s when a series of studies minimized the addictive nature of opioids right around the same time that organizations like the American Pain Society “campaigned to make pain what it called the 'fifth vital sign' that doctors should monitor, alongside blood pressure, temperature, heartbeat and breathing.”

Harold Jonas, PhD, LMHC, a Florida-based addiction counselor, and creator of an opioid recovery app called FlexDek MAT, believes the epidemic stems from what he sees as a uniquely American attitude, a “cultural phenomenon that goes with taking a pill, to have no symptoms at all and function at your highest level under the influence of different chemicals.”

PMZ21 is not a perfect painkiller, however, and it will be about a year or two before it goes into human clinical trials. While it relieves what Shoichet calls “conscious pain,” or the ongoing perception of pain, the drug does not affect “reflex pain,” which tells you to pull your hand away from a hot object before your brain actually registers your seared flesh. (Good news for the mice, at least: Placed on hot plates and dosed with PMZ21, they experienced as much pain relief as those on morphine without a dulled urge to jump off, according to Shoichet.)

Still, Shoichet says his team was “totally blown away by the results,” calling their discovery a “triumph of basic science.” Meanwhile, more progress is being made—another recent study published in the Nature journal Neuropsychopharmacology has found a brain mechanism that, if targeted by medication, could reduce one’s tolerance to morphine.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026. Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

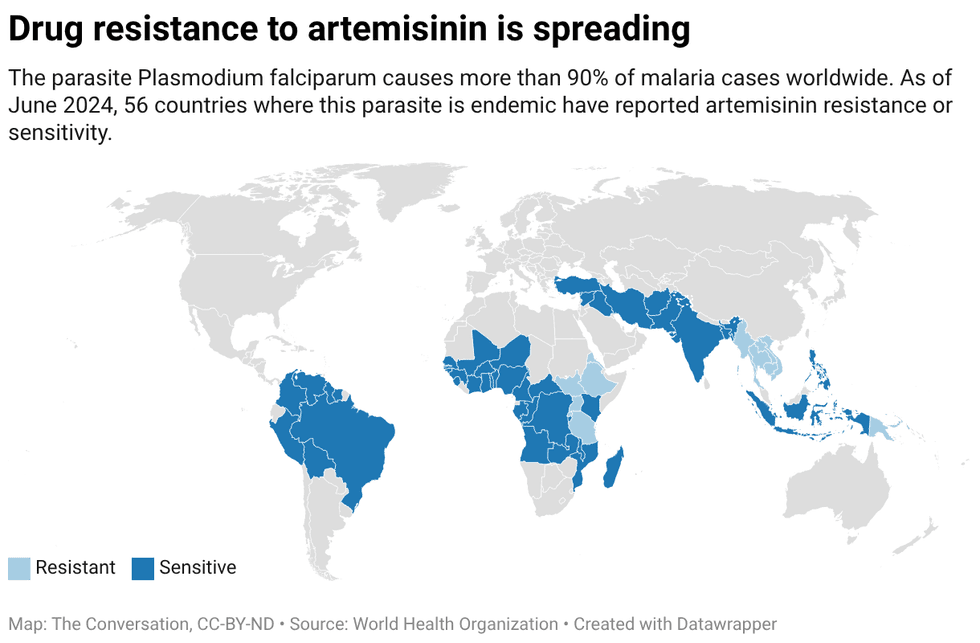

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with