My shooting instructor shows me how to control my breathing.

“Like in yoga?” I ask.

She responds with a nod, a chuckle, a shrug. Breathe in, breathe out, wait a beat. Fire. I see a yellow flash spark over the blackness of the XDm 9mm semi-automatic’s slide. I can feel the pistol recoiling in my hands, but not the terror I expected to feel. My shot lands well inside the target’s center square—a guileless sheet of paper printed with a vaguely human form now has a bullet in its chest.

“Congratulations! You just fired a real gun.” The sweet-faced and aptly named Amy Shotwell, my instructor at Ashburn, Virginia’s Silver Eagle Group, grins.

I set the gun down on the bench ahead of me, carefully pointing it downrange. A few lanes over, a middle-aged man in a white polo shirt empties his magazine, the drill of gunfire pelting his target so fast, it flutters like a leaf in the whipping wind.

“Want to take a minute?” Shotwell asks, eyebrows raised with some concern. “You okay?”

I shake out my arms. “I want to do it again.”

It’s almost four months to the day that I stood alongside my daughter and PETA volunteers, protesting the National Rifle Association’s tacky and ludicrous press conference a week after the Sandy Hook Elementary massacre. That week, NRA Vice President Wayne LaPierre poked fingers at video game violence, lambasted the media, and recommended armed guards in our schools. Just blocks from the White House, he ranted in a hotel ballroom while my baby slept bundled in her snowsuit and stroller with me outside. I held a sign that said “Teach kindness, not killing.”

Now, I gather up the surprising lightness of my rented gun, take aim, and fire again. Another slug blasts through the middle of my paper friend.

It has been a strange few months.

Immediately after the Newtown, Connecticut, shootings, I found myself compulsively tucking and retucking my kids into bed. “There but for the grace of God go I” flickered in my brain like a short-circuiting neon light. I hovered extra long over my son, a preschooler, my mind teetering precariously into macabre horrors—bullets flying, frail, lifeless bodies. Simultaneously, I was swallowed by fear and incensed with outrage. I mouthed off about right-wing gun nuts. I shuddered as more news broke about Adam Lanza and his paperback copy of Train Your Brain to Get Happy, his holiday check from his mother for the purchase of a C183. I emailed my editor at GOOD a copy of the letter that I’d written to the president demanding gun control, hoping whatever power either held could spur some action and stop the guns.

Now, at the behest of that same editor, I’ve stepped into foreboding new terrain. When I first learned that people like me were gravitating towards firearms at a moment like this, I was revolted. I’d come to equate every American gun owner with Lanza, with James Holmes, with Seung-Hui Cho. Mine was a perspective that not only lacked nuance, but that had strayed from reality. My own rhetoric had become a shorthand in which merely owning a gun threw a person into a camp of those who were cavalier with deadly weapons, whose personal rights trumped public safety, and who were politically alien to me.

Despite a debate that often seems to crack along hard lines of cultural stereotype (think weeping, anti-gun mom vs. NRA card-carrying wacko), an individual’s political affiliation is not ipso facto an expression of their attitude towards guns. According to a 2011 Gallup poll, 40 percent of Democrats said they have a gun at home. But perhaps more interesting, after 2012’s highly publicized mass shootings, anecdotal reports suggest that many on the left are increasingly embracing firearms. In Cleveland this winter, Kim Rodecker’s concealed-carry classes saw a modest increase in liberals among their ranks. Kelly Whitlock, owner of the Portland Gun Club in Oregon, says he’s noticed a shift in the sorts of people walking through his doors over the past year or so. He sees an abundance of lesbian couples and “a lot of younger guys that have the hair that stands up taller than Elvis’s would have, in skinny jeans and scarves.” But it’s not just Portland hipsters, true to form, defying type.

In the time since Sandy Hook, the partisan divide on guns—as it’s been portrayed in our media, our advocacy alerts, our dinner-table spats—has appeared to have become only more polarized. In the days following the shooting, 72 percent of liberals responding to a Washington Post-ABC News poll said they favored stricter gun control laws in the United States. But being neatly boxed in by ideological lines has set some liberals looking farther afield to define their own position on guns. While the trauma of mass shootings has sent many on the left—like Gabrielle Giffords and her family—into an out-front appeal for gun control, another subset of liberals have careened off in the other direction.

At the same time the elementary school massacre had me Googling “bullet-proof backpacks,” Adam Hilliker, from Newton, Massachusetts, was typing “liberal gun owners” into his search engine. Hilliker, a father of 2- and 4-year-old kids, is a liberal who says he felt conflicted about guns—a couple of bachelor parties at shooting ranges had piqued the interest of the mechanically inclined software engineer. After the Sandy Hook shootings, he went through the natural horror any parent would, but then also found himself repelled by the anti-gun sentiment he heard on the news. “It happened, and it was terrible, and the media just wouldn’t let it go...then there was the NRA’s ridiculous response, and then everybody’s backlash against that, and it just got bigger and bigger.”

Despite having grown up in an anti-gun household, “after the Newtown shootings, there was such a crazy backlash about it that I just needed some perspective,” he says. When Hilliker found other liberal gun owners online, he decided to take a class. Exploring firearms became a two-part quest to master a difficult skill and unravel a liberal taboo. By March, he’d applied for his gun license.

Outshouted by the vehement cocksure-ness of the NRA, liberal gun owners from all over the country quietly gather in groups like The Liberal Gun Club, an education and outreach organization that Ed Gardner, LGC director of operations and chair of the group’s education committee, says draws gun-owners who “do not want to be identified with that sort of rabid, anti-government, frankly, Republican-supporting-base.” LGC is not alone. There’s the Liberal’s Gun Corner podcast on the Gun Rights Radio Network. There’s the Blue Steel Democrats with caucuses in multiple states and the snappy bumper sticker motto: “Democrats don’t want your guns—we’ve got our own.”

Not so much a silent majority, but a quiet yet noteworthy block once I discovered them, liberal gun owners represented a unique entry point into a world I didn’t think I’d be able to understand. Rather than the boogeymen I imagined, these were people who in most respects were like me.

[image position="standard large" id="536878"]

There are myriad reasons I’d never touched a gun before my trip to the shooting range in Ashburn. I tend to drop things. I abhor violence. I possess a collection of distastes for loud noises, unpredictability—not to mention anything that can puncture my flesh. Thus, I began my intellectual walkabout with gun-owning liberals wondering, foremost, how anyone could be drawn to weapons at a cultural moment like the current one.

For Brandon E. Cox, it has been a lifelong puzzle. A backpacker and high-rigger, the Arizona resident was raised never even to play with toy guns. “And I had kind of just a knee-jerk reaction to guns.” Yet, in adulthood he got into firearms when a good friend took him shooting. It was fun. He’s a gearhead. It fit. Still, he understood my concerns when we talked about last year’s massacres.

“They are horrors, I mean, in the strictest sense of the word... they’re horrors in the most visceral and human way possible.” Cox’s tone was gentle. “But reconciling that with logic, and just putting numbers together, it doesn’t add up.”

Despite the high-profile mass shootings, and enough guns for every adult in the U.S., according to a Pew Research Center analysis of government data, the homicide rate is down 49 percent since a 1993 peak. By 2011, other violent crimes with firearms—assaults, robberies, sex crimes—were down 75 percent from 1993. According to the Centers for Disease Control, each year in the United States, approximately 11,000 people are killed in gun homicides. Nearly 20,000 die in gun suicides. Cox reminded me that in comparison more people (35,000) die in car accidents each year. According to data derived by Stephen Dubner and Steve Levitt in their book Freakonomics, a child is about 90 times more likely to die in a swimming pool than by gun.

For some liberals, doing the math—aligning policy with the available data— feels like a natural extension of their political philosophy. Marlene Hoeber, a “glorified mechanic” at a biotech firm, is a gun owner who describes herself as a “lefty feminist.” To Hoeber, the gun debate is the only time she sees the American left treating numbers and evidence as completely irrelevant, as though there is no reasonable political discussion to be had. Her characterization reminded me of years of willful denial of climate change on the right. But, says Hoeber, “the strategy of chipping away at rights looks an awful lot like the anti-choice movement to me.”

For those on the left, party-line antipathy around guns is a phenomenon of recent history. According to the massive General Social Survey, in the 1970s and 1980s, more Republican households owned guns than Democratic ones, but the distance between the parties’ ownership didn’t widen considerably until the early 1990s, around the time of the legislative fight over the Brady Bill.

Gardner at LGC also explains that being a Democrat between 2000 and 2008 was complicated. “If you weren’t with us, you were against us,” she says. The political divisiveness of the Bush/Cheney years made it tricky to be the sort of liberal who frequents a shooting range. Says Gardner, “For many years, obviously, this particular segment was dominated by the NRA, and as things got politically charged...folks of our political persuasion were increasingly unwelcome.”

For years they hid their love of firearms, but the block of liberal gun owners is slowly becoming more vocal. Since software engineer Hilliker has taken up shooting and began telling his liberal friends about his adoption of the sport, he’s discovered many were privately gun enthusiasts. “We didn’t really talk about this stuff because it’s pretty taboo, but then, when I started bringing it up, there were more people than I thought who were into guns.”

I joke with Hilliker that confessing to a love of firearms must, for some liberals, feel a lot like coming out—baring some private fact about yourself. He corrects me, “Yeah, except I think if I were coming out, it’s something I would feel more proud of.” Guns have a more negative stigma. “I feel like supporting gun culture isn’t as righteous as supporting gay culture.”

By most estimates, Americans own between 262 million and 310 million firearms, and as the drumbeat of gun control legislation has thumped louder, gun sales have only skyrocketed. Whitlock of Portland Gun Club regularly sees people showing up to class with guns still in the box, coming straight from the store. When I ask him why he thinks that is, he answers simply, “because they think it’s possible they won’t be able to have them anymore.” It’s an interesting time for Whitlock, a conservative who says his shooting slots are filling up increasingly with liberals. “They’re definitely not of the same mindset that I am by any means—and you wouldn’t normally picture them with guns, because their party is the one that wants to take them away from us.”

Hoeber says she finds the partisanship over gun rights perplexing. “I find it very odd that I have to make a political choice between people whose politics support all of the other civil liberties, or people who support gun ownership as a civil liberty, but none of the others. I mean, it’s a very odd political divide that doesn’t make a lot of sense, isn’t it?”

It’s a divide that has been perpetuated by one of Washington, D.C.’s strongest lobbies, the NRA, which has been cozying up to the Republican Party since the 1970s—often leaving those on the left, when it comes to guns, in a reflexive fighting stance.

Former staff writer for The New Yorker, self-described son of New Jersey Jewish Democrats, and Gun Guys author Dan Baum brought up a common, but worthwhile trope among gun owners when we spoke. “We just had this bombing at the Boston Marathon. You know if that had been done with a gun, we’d be talking about guns, but because it wasn’t done with a gun, we’re talking about alienation, trying to figure out why these guys did it.” After Sandy Hook, public discourse touched briefly on mental illness, and, says Baum, “I personally think it makes more sense to have the kind of conversation we’re having after the Boston Marathon bombing—why would young people do such a thing, rather than ‘let’s ban the guns.’”

[image position="standard large" id="536880"]

Perhaps overcoming a plague of alienation and violence is precisely where progressives are most needed at this moment of cultural upheaval. The violence in Newtown got those of us who don’t regularly experience violence thinking about it in a personal way, if briefly. But as Hoeber aptly pointed out to me, “You know it, nobody gives a shit about all the black kids that get shot in West Oakland, but you shoot 26 middle class white children in Connecticut, all of a sudden it’s a big fucking deal. And all of a sudden it’s about the big scary guns.”

And instead of dealing with so much else that is broken in this country, fear of those guns has instead translated into an attack on gun rights—rights that for many represent a fundamental and deeply felt freedom. The issue matters as much to some people—all along the political spectrum—as speech or religious freedoms matter to others. Baum tells me that most of us naturally understand the exceptionalism of the First Amendment: “We’re trusted to know things and speak and publish and print and broadcast. But it’s also very true in the context of guns, where we are trusted to own and operate these very dangerous weapons—and for gun guys [and girls], that’s an important thing.”

For LGC’s Gardner, Second Amendment protections matter, but don’t represent the whole of his political ideology. “I’m not a single-issue voter,” he tells me. “I care a great deal about things like marriage equality. I care a great deal about fairness in labor...I care about defense overspending. I do happen to care about Second Amendment rights.” He adds in summation, “I do shoot.”

When Hilliker wrote his gun license application letter to the police chief, he felt in some ways he was making an important political statement. He even wrote, “I think the more Democratic voters who are regis- tered gun owners the better, for the diversity of the conversation about gun ownership.” Later, at his licensing interview, the police chief let him know he thought his comment was pretty funny.

The right to keep and bear arms is serious business—for many it’s about self-defense. According to the Pew Research Center, while in 1999, just 26 percent of Americans owned guns for protection (49 percent had them for hunting back then), today 48 percent own guns for protection.

Hoeber’s perspective was sobering. Hoeber described herself as “Queer, trans...I have been in my life an outsider.” She says she doesn’t necessarily have the feeling that police are there to protect her, saying that if a fight broke out at a party at her house, “chances are I’m as likely to go to jail because it’s my house, and I’m me, as somebody who came to a party at my house and started a fight.” She adds, “The idea of ceding the monopoly on deadly force to the police or to the state or to the other authoritarian power structure, that’s completely fucking ridicu- lous to me.” Turning over that kind of power, to Hoeber, is a totally right-wing idea.

I was torn between an emotionally fraught rock and a rational hard place. I’d invested considerable time talking to lefty gun enthusiasts, then just hours before I shot a firearm for the first time, I spoke to Kim Russell, media director of Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, the viral Facebook-group-turned-grassroots- movement. Russell herself was a victim of gun violence. In a mugging that turned fatal, her friend was shot, Russell dodged bullets, and finally had a gun held to her forehead by a 17-year old with a tragic family history who only wanted their watches and wallets. I pictured the final emptiness she described, the life leaving her friend’s eyes.

I also kept picturing tiny bodies mas- sacred in kindergarten classrooms or the teenagers much more frequently gunned down in the Chicago neighborhood where I used to live. In the same way that I can’t think “lemon” without also thinking “sour,” I couldn’t picture a gun without revulsion and fear.

“Fairness is an important, critical core value on the left,” Hoeber tells me. “And I think one of the ways that sense of fairness exists on a deeply emotional level is really strong and negative feelings toward bullies.” She sees the anti-gun impulse on the left as an association between guns and bullies. “The gun is the dangerous power of the redneck, the Klansman, and the bad cop, and the unjust military dictatorship.”

She uses “bullies” in the broadest sense possible, but wonders how few of us, since World War II, have had an experi- ence of guns and violence being used to protect us from bullies. Calling for patience, she reminds her fellow lefty gun owners that the anti-gun impulse among other liberals “comes from wanting to take the power away from those who would subjugate others.”

It’s immense power that can come from the mere flick of a finger. When I finally held a pistol, then a revolver in my hands, I could feel the potential costs of carelessness. It was an intimate handshake, albeit briefly, with the Grim Reaper. And I was clutching between the two palms of my hands both totem and taboo.

A gun, it seems, is a symbol of momentous heft.

I don’t know what runs through a hunter’s head when he or she looks at a Remington 700 .30-06. But I was begin- ning to see that the tension over guns was less a matter of political leaning, and more a matter of the gun’s place in a person’s imagination, a matter of which direction the barrel aimed: if it were your kids imperiled, or yours you were protecting.

I think of Russell, the memory ever- present in her mind of a muzzle pressed to her forehead. I consider Hilliker, a dad, making sense of tragedy by demystifying the gun. I see in my own hands the blast, the thump of fear and adrenaline in my veins, and my finger depressing the trigger again. I know that however much it still scares the hell out of me to extend my body into the thrust and trajectory of a bullet, were the threat of harm to come to me or my children, I’d want to stand on this side of the gun—not aiming to kill, never to kill—but to have some force behind which to salvage what I love.

Illustrations by David Schwen

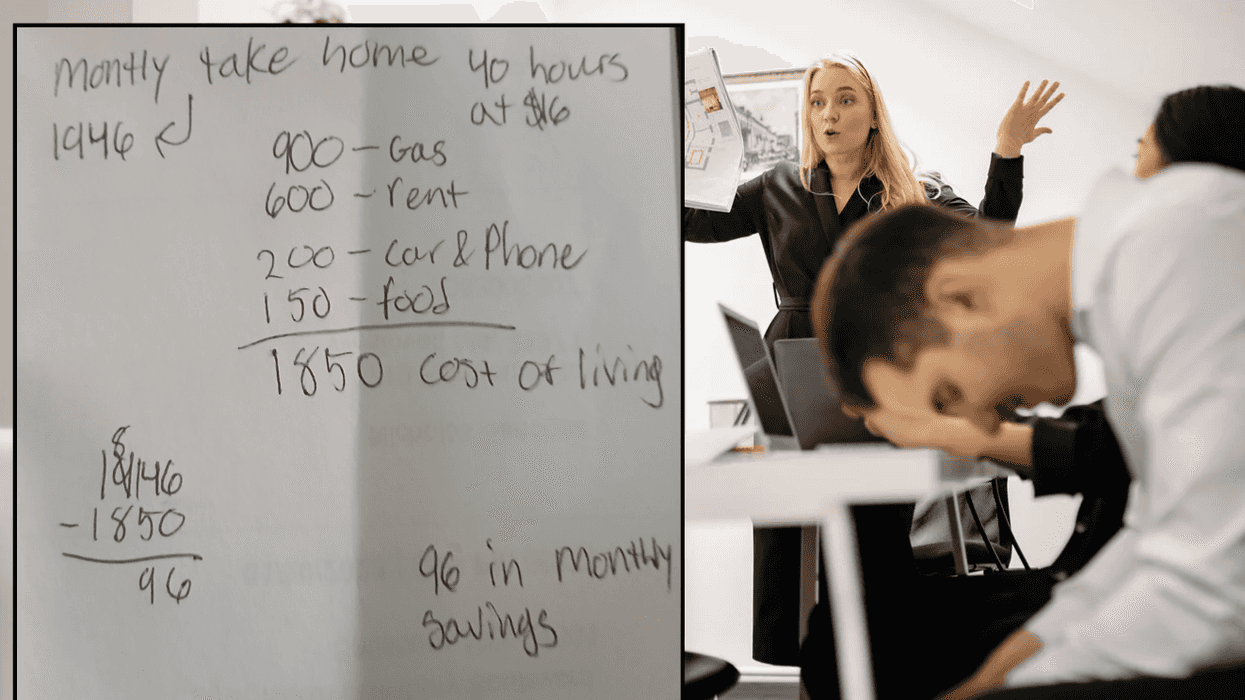

A young person doing their monthly budgetCanva

A young person doing their monthly budgetCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva

A young woman scrolling on her phoneCanva Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via

Gig of two cartoon penguins watching TV via  Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via

Gif of a storm trooper flipping through sings that say 'no' via