Imagine being young and healthy, a nonsmoker with no preexisting health conditions, and then waking up one morning feeling like you were being suffocated by an unseen force. Back in March, this was my reality.

I had just returned from Europe, and roughly 10 days later started having flu-like symptoms. I became weak overnight and had trouble breathing. It felt like jogging in the Rocky Mountains without being in condition, only I wasn't moving. I went to the hospital, where I was tested for COVID-19.

I was one of the first people in Texas given a non-FDA-approved test. My results came back negative. As a social epidemiologist who deals with big data, I was certain it was a false negative.

More than four months later, the symptoms have not gone away. My heart still races even though I am resting. I cannot stay in the sun for long periods; it zaps all of my energy. I have gastrointestinal problems, ringing in the ears and chest pain.

I'm what's known as a long-hauler – part of a growing group of people who have COVID-19 and have never fully recovered. Fatigue is one of the most common persistent symptoms, but there are many others, including the cognitive effects people often describe as brain fog. As more patients face these persistent symptoms, employers will have to find ways to work with them. It's too soon to say we're disabled, but it's also too soon to know how long the damage will last.

The frustration of not knowing

What made matters worse in the beginning was that my doctors were not certain I had COVID-19. My test was negative and I had no fever, so my symptoms did not fit into early descriptions of the disease. Instead, I was diagnosed with a respiratory illness, prescribed the Z-pack antibotic and a low dosage of an anti-inflammatory medication normally used for arthritis patients.

A Yale study released in May shows COVID-19 deaths in America do not reflect the pandemic's true mortality rate. If I had died at home, my death would not have been counted as COVID-19.

By the end of March, I was on the road to recovery. Then I had a seizure. In the ER, the doctor said I had COVID-19 and that I was lucky – tests showed my organs did not have lasting damage. After the seizure, I lay in my bedroom for weeks with the curtains drawn, because light and sound had started to hurt.

The search for answers

I did not understand why I was not recovering. I began searching for answers online. I found a support group for people struggling with COVID-19 long-term. They called themselves long-haulers.

COVID-19 support groups show that there are many people not considered sick enough to be hospitalized – yet they are experiencing symptoms worse than the flu. It is possible COVID-19 is neurotoxic and is one of the first illnesses capable of crossing the blood-brain barrier. This might explain why many people like me have neurological problems. Many long-haulers are experiencing post-viral symptoms similar to those caused by mononucleosis and myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome.

A common frustration is that some medical doctors dismiss their complaints as psychological.

One woman in the support group wrote: "140 days later, so many are hard to breathe, and no doctors will take me seriously as I was diagnosed with a negative swab and negative antibodies."

Paul Garner was the first epidemiologist to publicly share his COVID status. He described his 7-week fight with the coronavirus in a blog post for the British medical journal The BMJ. In July, I was interviewed by ABC. That month, an Indiana University researcher working with an online community of long-haulers released a report identifying over 100 symptoms, and the CDC expanded its list of characteristics that put people at greater risk of developing severe COVID-19 symptoms. On July 31, the CDC also acknowledged that young people with no prior medical issues can experience long-term symptoms.

It's still unclear why COVID-19 impacts some people more severely than others. Emerging evidence suggests blood type might play a role. However, data are mixed.

A Dutch study found immune cells TLR7 – Toll-like receptor 7 located on the X chromosome – which is needed to detect the virus is not operating properly in some patients. This allows COVID-19 to move unchecked by the immune system. Men do not have an extra X chromosome to rely on, suggesting that men, rather than women, may experience more severe COVID-19 symptoms.

Many COVID-19 survivors report having no antibodies for SARS-CoV-2. Antibody tests have a low accuracy rate, and data from Sweden suggest T-cell responses might be more important for immunity. Emerging evidence found CD4 and CD8 memory T-cell response in some people recovered from COVID-19, regardless of whether antibodies were present. A La Jolla Institute for Immunity study identified SARS-CoV-2-specific memory T-cell responses in some people who were not exposed to COVID-19, which might explain why some people get sicker than others. The complete role of T-cell response is unknown, but recent data are promising.

Looking ahead in an economy of long-haulers

Like many long-haulers, my goal is to resume a normal life.

I still grapple with a host of post-viral issues, including extreme fatigue, brain fog and headaches. I spend the majority of my day resting.

A big challenge long-haulers face may be sustaining employment. Ultimately, it is too early to classify long-haulers as having a disability. Anthony Fauci reported that "it will take months to a year or more to know whether lingering COVID-19 symptoms in young people could be chronic illnesses."

Economics is a big driver of health, and the link between employment and health care in America further exacerbates the need to maintain employment to protect health. Employers need to be ready to make accommodations to keep long-haulers working. The stress of being sick long-term, combined with the possibility of job loss, can also contribute to mental health issues.

To effectively fight COVID-19 and understand the risks, these patients with continuing symptoms must be studied. Online support groups, meanwhile, are helping long-haulers feel understood.

Margot Gage Witvliet is an Assistant Professor of Social Epidemiology at Lamar University.

This article first appeared on The Conversation. You can read about it here.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

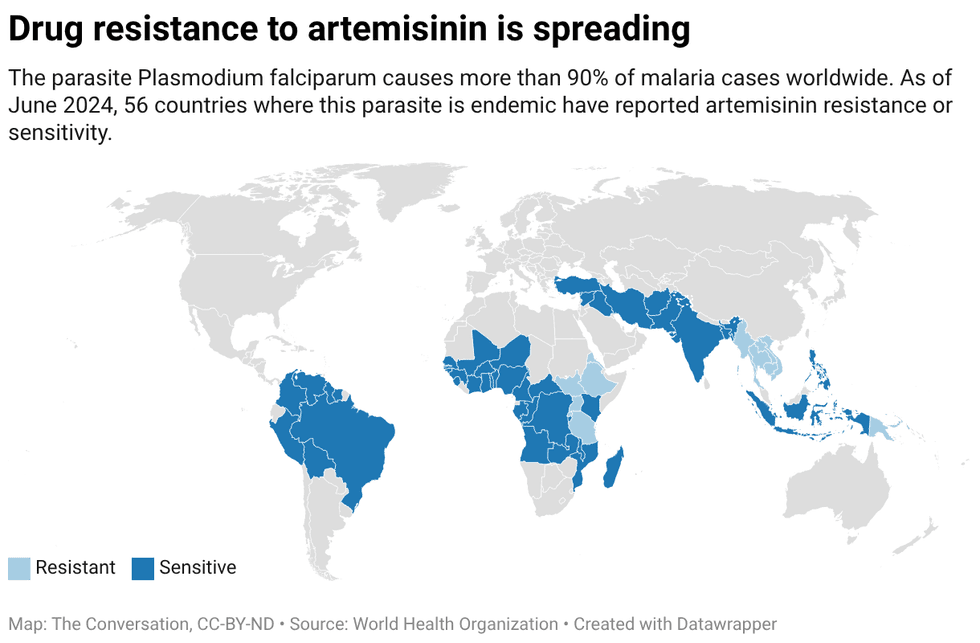

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.