Since day one of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S.

has not had enough tests. Faced with this shortage, medical professionals used what tests they had on people with the worst symptoms or whose occupations put them at high risk for infection. People who were less sick or asymptomatic did not get tested. Because of this, many infected people in the U.S. have not been tested, and much of the information public health officials have about the spread and deadliness of the virus does not provide a complete picture.

Short of testing every person in the U.S., the best way to get accurate data on who and how many people have been infected with the coronavirus is

I am a

professor of health policy and management at Indiana University, and random testing is exactly what we did in my state. From April 25 to May 1, our team randomly selected and tested thousands of Indiana residents, no matter if they'd been sick or not. From this testing we were able to get some of the first truly representative data on coronavirus infection rates at a state level.

We found that

2.8% of the state's population had been infected with SARS–CoV–2. We also found that minority communities – especially Hispanic communities – have been hit much harder by the virus. With this representative data, we were also able to calculate out just how deadly the virus really is.

The process of random testing

The goal of our study was to learn how many Indiana residents, in total, were currently or had been previously been infected by the coronavirus. To do this, the people our team tested needed to be an accurate representation of Indiana's population as a whole and we needed to use two tests on every person.

With the help of the Indiana State Department of Health, numerous state agencies and community leaders,

we set up 70 testing stations in cities and towns across Indiana. We then randomly selected people from a list created using state tax records and invited them to get tested, free of charge. Some groups showed up more readily than others and we adjusted the numbers to represent the demographics of the state accordingly.

Once a person showed up to our mobile testing sites, they were given both

a PCR swab test that looks for current infections and an antibody blood test that looks for evidence of past infection.

By testing randomly and looking for both current and past infections, we could extrapolate our results to the entire state of Indiana and get information about real infection rates of this virus.

The research team also worked with civic leaders from vulnerable communities to conduct open, nonrandom testing as well to see how the results of these two testing approaches would differ.

How widespread and how deadly

We tested more than 4,600 Indiana residents as part of the first wave of testing in the study. This included more than 3,600 randomly selected people and more than 900 volunteers who participated in open testing.

During the last week in April, we estimate that 1.7% of the population had active viral infections. An additional 1.1% had antibodies, showing evidence of previous infection. In total, we estimate that

2.8% of the population currently were or had previously been infected with the coronavirus with 95% confidence that the actual infection rate is between 2% and 3.7%.

Because our random sample was designed to be representative of the population of the state, we can assume with almost certainty that the entire state numbers are the same. That would mean that approximately 188,000 Indiana residents had been infected by late April. At that point, the official confirmed cases – not including deaths –

Focusing the tests on severe or high-risk people underestimated the true infection rate by a factor of 11.

Having a reliable estimate of the true number of people who have been infected also allowed us to calculate the infection fatality rate – the percentage of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 who die. In Indiana, we calculated the rate is 0.58%. For this calculation, we divided the number of COVID-19 deaths in Indiana – 1,099 at the time – into the total number of people that were determined to have been cumulatively infected at 2.8% of the population – 188,000.

Early estimates suggested that

5% to 6% of cases in the U.S. were fatal, which is similar to the 6.3% that you would get by dividing confirmed cases in Indiana – 17,000 – by the deaths – 1,099. The infection–fatality rate of 0.58% is thankfully far lower, but is nearly six times higher than the seasonal flu which has a death rate of 0.1%.

This random testing also allowed us to make accurate estimates about what percent of infected people are asymptomatic. In our study, about 44% of those who tested positive for active viral infection reported no symptoms. While this was already

suspected by experts, our estimate is likely the most accurate to date.

Race, job and living situation matter

The general trends and information about the virus are incredibly important, but just as important are the ways in which human actions influenced what people are most affected.

We asked every person we tested about their race, ethnicity and whether they lived with someone who was previously diagnosed with COVID-19.

Our analysis of the random sample suggests that COVID-19 rates are much higher in minority communities, especially in Hispanic communities, where approximately 8% were currently or previously infected. While we do not definitively know why, it is possible that members of the Hispanic community in Indiana are

more likely to be essential workers, live in extended family structures that include relatives beyond the nuclear family or both.

We further found that people who lived with a person who was COVID-19 positive were approximately 12 times more likely to have the virus themselves than people living in a home with no infections. Living with extended family and being more exposed due to one's job may make it easier for the virus to spread within some communities.

These findings, along with the relatively low 2.8% prevalence, suggest that social distancing slowed the spread of the virus in the larger population. However, the hardest-hit communities were those who, on average, are not able to practice social distancing as consistently as others.

What next?

Now that we have this information and have established a baseline, we will continue periodically testing a random sample of people in the state. Doing so will tell us how far the virus has infiltrated our population so that policy decisions can be tailored to the situation.

This is the first statewide random sample study in the U.S. and the numbers offer both points of hope and concern.

The good news is that social distancing worked. Efforts to slow the virus contained it to only 2.8% of the population and by slowing the spread of the virus in the community, Indiana bought some time to determine the best way forward. This provides more time for researchers to both determine the degree to which infection results in immunity and to accelerate the development of a vaccine.

But there is bad news as well. If only 2.8% of the population have been infected with SARS-CoV-2, 97.2% of the population have not been infected and could still get the virus. The risk for a large outbreak that could dwarf the initial wave is still very real.

The demographic distribution of infections, while disturbing, offers important information that can help public health officials direct testing, education and contact tracing resources that are language and culturally sensitive. The research team and the state health department are working with leaders from these communities to figure out how to best contain the spread of the virus in the areas most affected.

As businesses slowly reopen, we need to be vigilant with any and all safety precautions so that we do not lose the ground we gained by hunkering down. Hopefully numbers will go down, but regardless of what happens in the future, we now better know the foe we fight.

Nir Menachemi is a Professor of Health Policy and Management at IUPUI.

This article first appeared on The Conversation. You can find it here.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

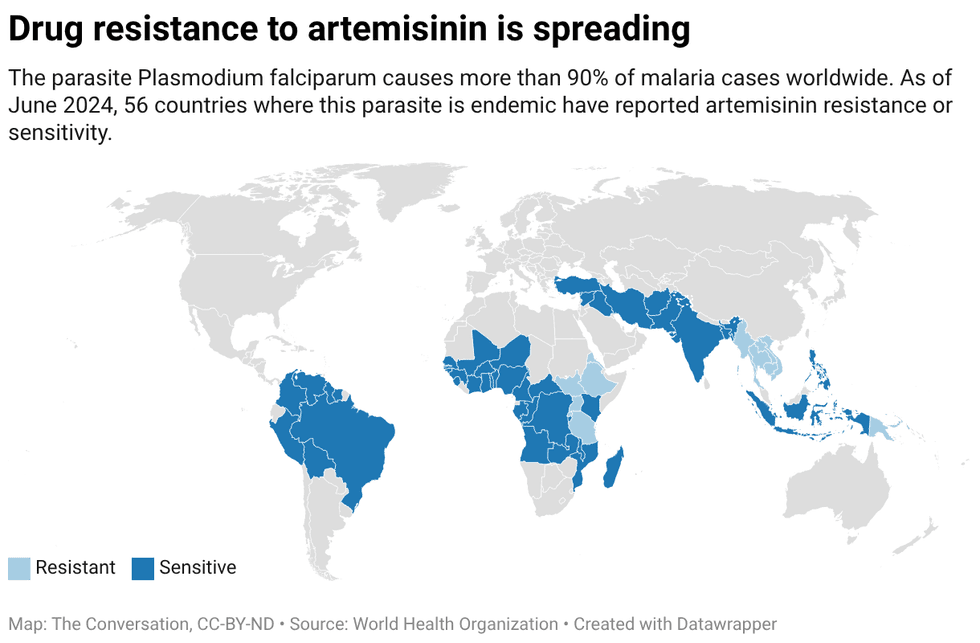

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with