While new medical discoveries and innovations are in the news every day, doctors struggle daily with using information and techniques available right now, while carefully adopting new concepts and treatments. As a practicing doctor, I deal with uncertainties and unanswered clinical questions all the time.

I encounter two key limitations in making the best possible decisions for my patients under any circumstances. First, while there are reams of information in books and online, doctors often lack the time to find and digest it all. Instead, we must work with what we carry in our heads, from personal experience and education. Another constraint, perhaps even more important, is that the information available is usually not focused on the specific individual or situation at hand.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Part of the problem is that health records are traditionally kept on paper, making them hard to analyze en masse.[/quote]

For example, there are general guidelines for the ideal blood pressure a patient with a severe infection should have. However, the truly best target blood pressure levels likely differ from patient to patient, and perhaps even changes for an individual patient over the course of treatment.

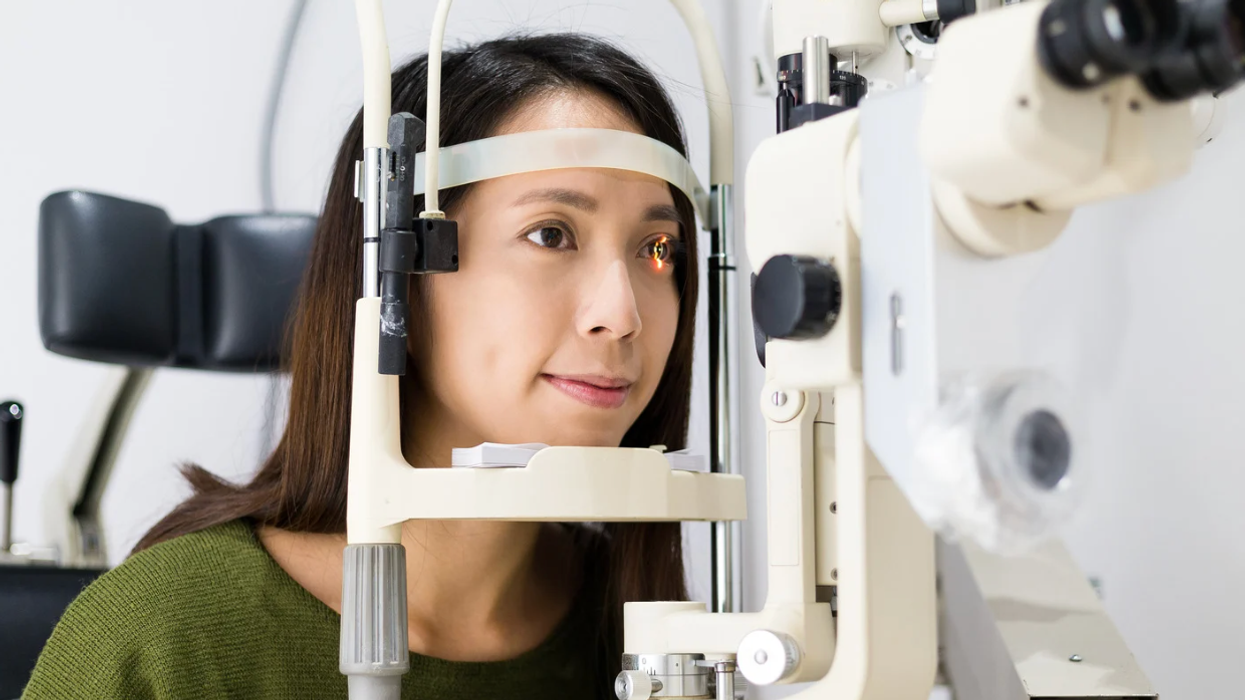

The ongoing computerization of health records presents an opportunity to overcome these limitations. Analyzing electronic data from many doctors’ experiences with many patients, we can move ever closer to answering the age-old question: What is truly best for each patient? In countries with advanced health care systems, we can find optimal care by improving analysis of the data doctors already collect. In poorer and more rural countries, we must first collect that data before being able to analyze it. In both cases, medical professionals and data scientists need to work together to improve health care for everyone.

Toward individual application of mass data

This type of data-driven approach could be very useful. At the moment, a report from the National Academy of Medicine tells us that most doctors base most of their everyday decisions on guidelines from (sometimes biased) expert opinions or small clinical trials. It would be better if they were from multicenter, large, randomized controlled studies, with tightly controlled conditions ensuring the results are as reliable as possible. However, those are expensive and difficult to perform and, even then, often exclude a number of important patient groups on the basis of age, disease, and sociological factors.

Part of the problem is that health records are traditionally kept on paper, making them hard to analyze en masse. As a result, most of what medical professionals might have learned from experiences is lost—or at least is inaccessible to another doctor meeting with a similar patient.

A digital system would collect and store as much clinical data as possible from as many patients as possible. It could then use information from the past—such as blood pressure, blood sugar levels, heart rate, and other measurements of patients’ body functions—to guide future doctors to the best diagnosis and treatment of similar patients.

Industrial giants such as Google, IBM, SAP, and Hewlett-Packard have also recognized the potential for this kind of approach, and are now working on how to leverage population data for the precise medical care of individuals.

Collaborating on data and medicine

At the Laboratory for Computational Physiology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, we have begun to collect large amounts of detailed patient data in the Medical Information Mart in Intensive Care (MIMIC). It is a database containing information from 60,000 patient admissions to the intensive care units of the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, a Boston teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School. The data in MIMIC has been meticulously scoured so individual patients cannot be recognized, and it is freely shared online with the research community.

But the database itself is not enough. We bring together front-line clinicians (such as nurses, pharmacists, and doctors) to identify questions they want to investigate, and data scientists to conduct the appropriate analyses of the MIMIC records. This gives caregivers and patients the best individualized treatment options in the absence of a randomized controlled trial.

Bringing data analysis to the world

At the same time, we are working to bring these data-enabled systems to assist with medical decisions to countries with limited health care resources, where research is considered an expensive luxury. Often these countries have few or no medical records—even on paper—to analyze. We can help them collect health data digitally, creating the potential to significantly improve medical care for their populations.

This task is the focus of Sana, a collection of technical, medical, and community experts from across the globe that is also based in our group at MIT. Sana has designed a digital health information system specifically for use by health providers and patients in rural and underserved areas.

At its core is an open-source system that uses cell phones—common even in poor and rural nations—to collect, transmit, and store all sorts of medical data. It can handle not only basic patient data such as height and weight, but also photos and X-rays, ultrasound videos, and electrical signals from a patient’s brain (EEG) and heart (ECG).

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]Cell phones—common even in poor and rural nations—can collect, transmit, and store all sorts of medical data.[/quote]

Partnering with universities and health organizations, Sana organizes training sessions (which we call “boot camps”) and collaborative workshops (called “hackathons”) to connect nurses, doctors, and community health workers at the front lines of care with technology experts in or near their communities. In 2015, we held boot camps and hackathons in Colombia, Uganda, Greece, and Mexico. The boot camps teach students in technical fields like computer science and engineering how to design and develop health apps that can run on cell phones. Immediately following the boot camp, the medical providers join the group and the hackathon begins.

Originally the brainchild of Silicon Valley, a hackathon brings people from different fields together over a short period of time to attack a specific problem or type of problem. At Sana events, attendees focus on a specific health problem, such as how to screen rural populations for heart disease or monitor children with epilepsy using cell phones.

Teams build prototype apps to address specific problems the doctors and nurses have encountered. Some projects from the hackathon are continued as research or startup ventures.

Delivering better health care through technology

In Mexico City at the beginning of 2016, Sana held a boot camp hackathon focusing on the health needs of older people. Joining the efforts of the engineering department of the local university, Tec de Monterrey, and geriatricians at a local hospital, it produced several promising prototype applications.

One app would help to provide patients with exercises to control urinary incontinence. An “Uber-like” app would connect families with caretakers—relieving them from relying on word of mouth or worse, the phone book. A third “Tinder-like” app would help elderly people find others with similar interests, reducing their social isolation. The collaborations continue to further develop the prototypes and test a few of them in the hospital and clinics.

At the end of the day, though, the purpose is not the apps. By fostering relationships among engineers, health care providers, and even patients, the Sana and MIMIC projects are helping to move medicine into a truly functional and beneficial digital age.

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:  Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:

Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:  Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit:

Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit: