Two years ago, Stephen Estrada was a happy 28 year old, enjoying the prime of his life. He was in a great relationship, he loved his job as a hairdresser, he took good care of himself by eating healthy, and he was in the gym all the time.

But he always had this nagging pain in his abdomen. And once, he noticed blood in his stool. He didn’t think much of it, but then the pain worsened. It got so bad he went to the emergency room (twice), but the doctors there told him nothing was wrong. They seemed to think he was trying to get painkillers. Finally he got an appointment with his primary care physician.

“I told her, ‘I don’t know what cancer feels like, but I have a feeling that’s what this is,’” he says. She told him he was too young. But Estrada could feel that the lymph nodes in his back were swollen to the size of peaches. “I need you to feel this,” he told her. “And as soon as she felt it, her face changed.”

Estrada was rushed in for a CT scan, which revealed Stage IV colon cancer. Within weeks, his doctors were discussing plans to keep him comfortable during end-of-life care.

“It was probably the first time in my life where I actually felt like it would be easier to not be around anymore,” Estrada says.

He needed someone to talk to. His doctors recommended colon cancer support groups, but the other patients were all much older than he was. Then one day, he saw a local newspaper in his oncologist’s office. It was from a place he’d never heard of—“Colontown.”

While breast cancer gets “Save the Boobies” t-shirts and all-pink-everything awareness campaigns; prostate cancer gets Movember; and skin cancer gets a Marc Jacobs line, colorectal cancer is rarely a part of the mainstream conversation. Yet it’s the second most fatal cancer in the United States, and incidences among young people (under 50) are on the rise. Many colon cancer patients like Estrada feel isolated and hopeless after their diagnosis.

When Erika Hanson Brown was diagnosed at 58, she had this experience. But she’s not one to sit around and lament an unsolved problem. Instead, she founded Colontown. An online “town” of over 2,500 “residents,” of which she is the mayor.

Brown, a Colorado resident, previously worked as a corporate recruiter, or a “professional networker” as she calls it. But when she got sick, she found that no one within her huge network had anything to say about colon cancer. People either had no experience with it, or they just weren’t comfortable talking about anything related to colons, rectums, and anuses.

But “the only thing that would have made me feel better is to talk to someone,” Brown says. So she put her professional networking skills to work, and Colontown was born.

Colontown exists on Facebook, but it’s not your typical Facebook group. It’s made up of over 40 neighborhoods dedicated to specific diagnoses and patient needs. There’s the Poop Chute Group for people with colon cancer; the Four Corners for Stage Four patients; and Care Partner Corner for caregivers.

“Each one of the neighborhoods are led by someone with exactly that experience,” Brown says. “The centralized group is Downtown, and that’s always busy.” Prospective members are personally vetted by Brown, and a welcoming committee of 16 people introduces every new member to the community and connects them to the appropriate neighborhoods.

Some of the most active neighborhoods are the Colontown Clinics—groups, sorted by tumor genetic profiles, dedicated to sharing clinical trial information and opportunities. Clinical trials can be the best (and sometimes only) hope for cancer patients, but they’re not always easily accessible. Every oncologist across the country isn’t familiar with every available trial, so you can’t count on your doctor to know about them all and recommend one. The National Institutes of Health maintains a database of all ongoing trials, but both doctors and patients have a hard time navigating it.

Dr. Christopher Lieu, who works in the Colorectal Cancer Multidisciplinary Clinic at the University of Colorado Denver, says patients who visit Colontown bring him information about clinical trials and treatments that is even new to him—and he’s a colorectal cancer specialist. “I always like to think that we’re doing this for the patient already, but I think oftentimes we’re not.”

Colontown “arms the patient with more information,” Lieu says, and it’s good information, more curated than the full libraries of information available on the internet. Informed patients can come to doctors like Lieu with high-quality ideas and questions or with clinical trials they want to sign up for, and it helps him provide better care.“There’s really this trend towards an openness of communication,” he says. “It used to be doctors just telling patients, ‘This is what you’re going to do. Don’t ask me any questions’.”

For Stephen Estrada, the clinical trial information shared on Colontown was lifesaving. Through some of his Colontown neighbors, he heard about an immunotherapy trial taking place in Colorado, and they were looking for patients with exactly his type of cancer. He started the new treatment a year and a half ago, and today his tumor has shrunk to half its original size—and it’s still shrinking. He’s regained weight; his hair has grown back; and he’s working again. He’s part of the town government now, helping run the Clinic and the Four Corners.

Brown’s primary mission is to help patients be their own advocates and to learn about their own disease and seek out the support they need. She’s working to expand the Colontown model to other cancers. “I’ve got a global vision. The internet works for that,” she says.

“When you’re diagnosed with cancer, it’s such a scary thing, and everything’s moving so quickly and so slowly at the same time,” Estrada says. “Everyone could benefit from a support group like Colontown. It really had a hand in saving my life.”

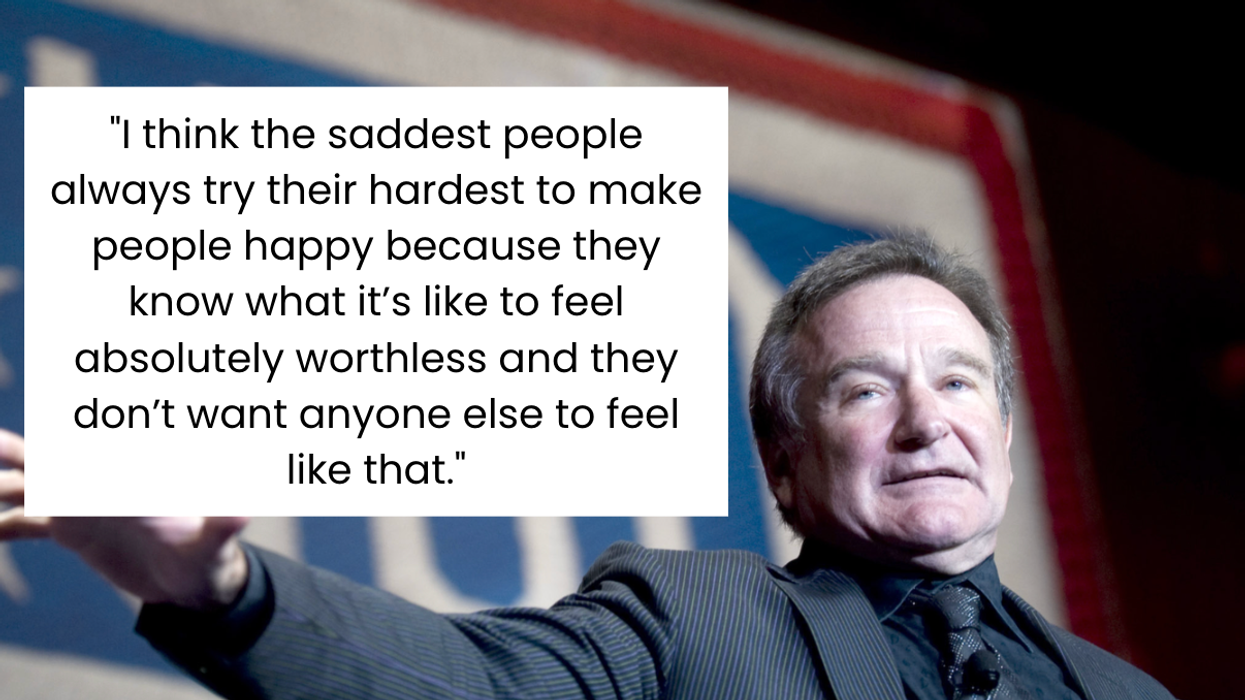

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007 Gif of Robin Williams via

Gif of Robin Williams via

A woman conducts a online color testCanva

A woman conducts a online color testCanva A selection of color swatchesCanva

A selection of color swatchesCanva A young boy takes a color examCanva

A young boy takes a color examCanva

Pictured: A healthy practice?

Pictured: A healthy practice?

Is solo sleep the best sleep?

Is solo sleep the best sleep?  Some poeple want their space, and some can't imagine being that seperate.

Some poeple want their space, and some can't imagine being that seperate.

Professor shares how many years a friendship must last before it'll become lifelong