If you’re one of those people who really wants to match people’s names to their faces but just can’t do it, it might not be your fault. (Note: If you don’t care about remembering people’s faces, then it IS still your fault). A condition known as prosopagnosia, better known as “facial blindness” affects 2.5% of the world’s population to some degree.

It’s believed that while some are born with the condition, others develop it over time, often after a traumatic event like a concussion, stroke, or brain injury. Unfortunately, there’s no medical treatment, but a diagnosis is still helpful in managing the condition in one’s daily life. While facial blindness may sound trivial or even more like a “quirk” than a hardship, severe cases can profoundly impact the way people live.

A New Yorker feature from last year profiled several sufferers and revealed the many ways prosopagnosia can hinder people from living a “normal” life. One anonymous person interviewed for the piece stated, “I’ve walked right past my husband, my own mother, my daughter, my son, without being able to recognize them.”

Summarily, people suffering from face blindness just don’t see the face as a defining characteristic of a person. Some don’t see faces as even being distinct features from person to person. Artist Chuck Close said in the same feature that he must find a way to manipulate the face into something memorable to him, stating, “Once I change the face into a two-dimensional object, I can commit it to memory.”

The severe instances of the condition inhibit social interaction in virtually ever manner. Those suffering from facial blindness are more prone to other disorders, including a general disinterest in people, anxiety, and a development of agoraphobia or clinical aversion to crowded, busy areas.

Strangely, there are also incidental benefits to suffering from the condition. The anonymous New Yorker subject said once she had been praised for her interaction (as a white woman) with African-Americans, stating:

When I worked at a homeless shelter, I was often praised for the way I interacted with my African-American clients. I couldn’t figure out what I was doing differently from the other white workers, but I was allowed into their circle and they bonded with me. When we lived in Louisiana, I was always being asked by African-American women if my husband was black.

While research on the issue still borders on nascency, the fascinating nature of prosopagnosia has captured the attention of the media, which has been quick to cover firsthand accounts of what it’s like to just...not see faces on people.

CBS News offered a two-part study on the disorder and how it affects those afflicted:

Further, this five-minute video from the World Science Festival puts those with facial blindness to the test by actually having them recall and identify faces on the spot in a theater full of people, offering further insight into the struggle of people who can’t recognize the faces of some of the world’s most famous people:

It’s a condition that’s nearly impossible to self-diagnose (probably because so many of us like to think we have it as a crutch), and even if it manifests, there’s a broad spectrum of severity that ranges from nearly imperceptible to socially debilitating. Precise testing is required for any level of certainty, however.

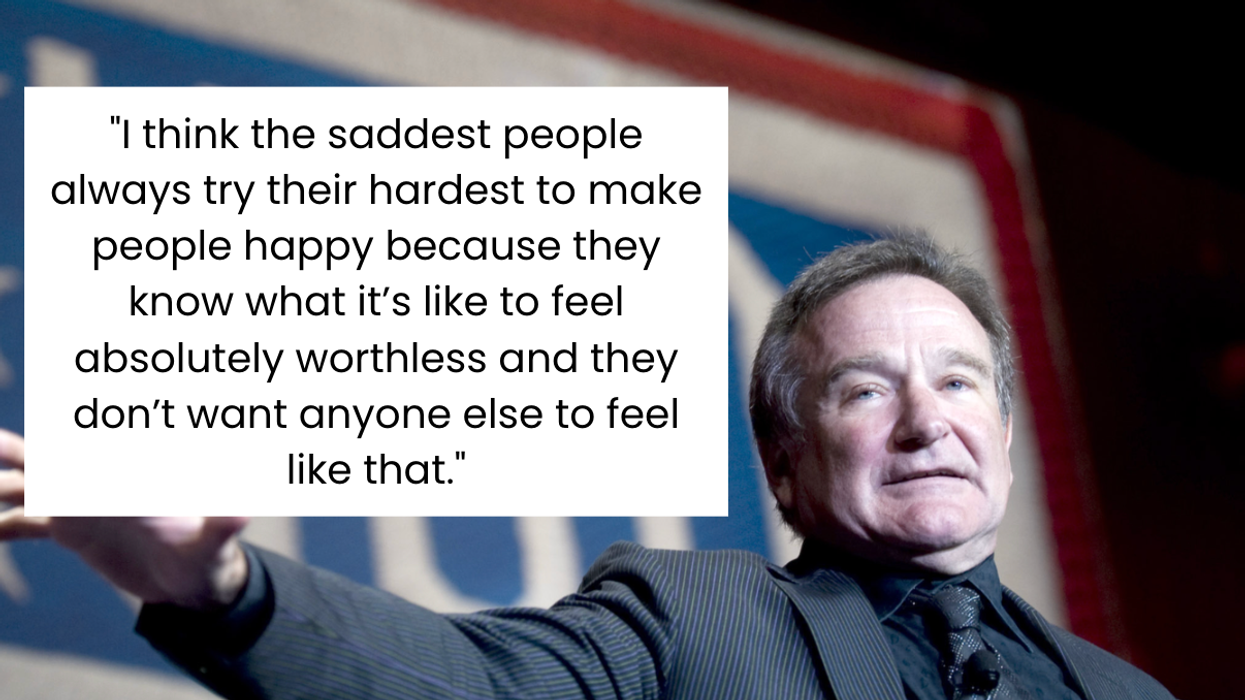

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007

Robin Williams performs for military men and women as part of a United Service Organization (USO) show on board Camp Phoenix in December 2007 Gif of Robin Williams via

Gif of Robin Williams via

A woman conducts a online color testCanva

A woman conducts a online color testCanva A selection of color swatchesCanva

A selection of color swatchesCanva A young boy takes a color examCanva

A young boy takes a color examCanva

Pictured: A healthy practice?

Pictured: A healthy practice?

Is solo sleep the best sleep?

Is solo sleep the best sleep?  Some poeple want their space, and some can't imagine being that seperate.

Some poeple want their space, and some can't imagine being that seperate.