A new tool is emerging in the fight against antibiotic-resistant bacterial disease. Beyond the global efforts to limit overuse and abuse of antibiotic drugs, nanomedicine is finding additional ways to attack these superbugs. Nanoparticles, a million times smaller than a millimeter, are proving to be stable, easy to deliver, and readily incorporated into cells.

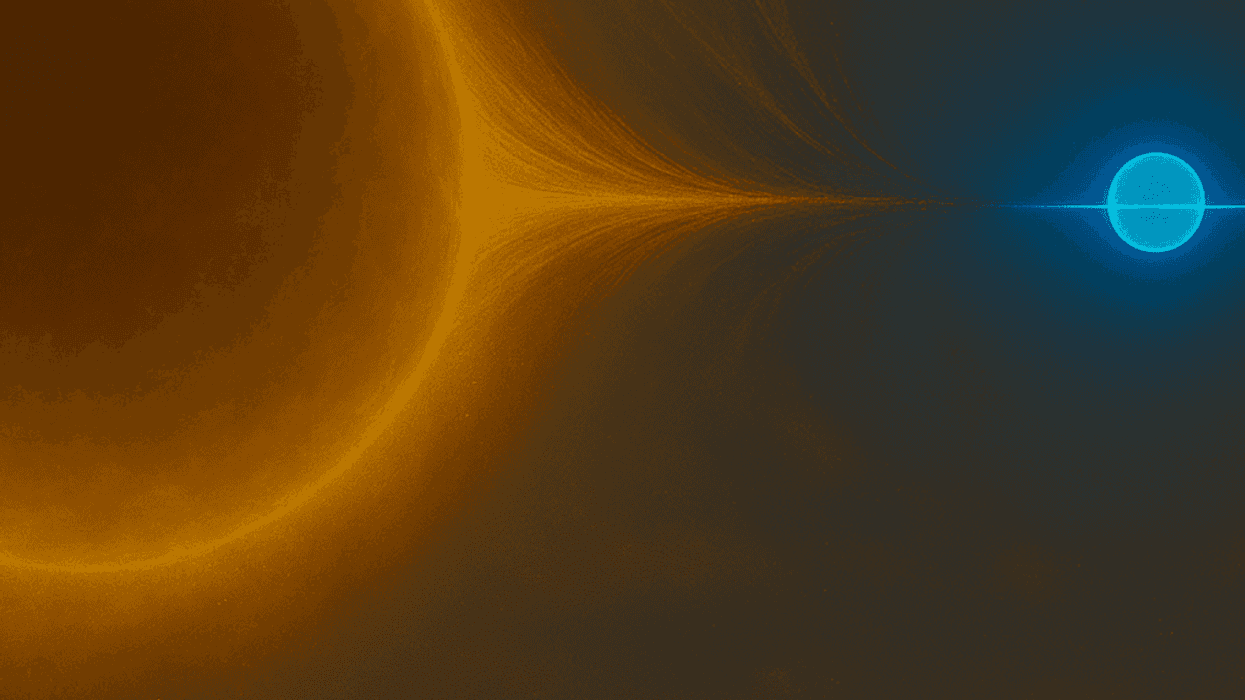

In recent work, a group of researchers at the University of Colorado, of which I am a member, have used nanoscale quantum dots—minuscule semiconductor particles with specific light-absorption properties—to kill drug-resistant superbugs without harming the surrounding healthy tissue.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Superbugs, or bacteria that are resistant to more than one antibiotic drug kill more than 700,000 people each year.[/quote]

Once introduced into the body, the quantum dots do nothing until they are activated by having a light shined on them. Any visible light source (a lamp, room light or even sunlight) can be used for this. So far our research has focused on topical infections on the skin; deeper inside the body, brighter lights or more nanoparticles may be needed.

When activated by light, the quantum dots start generating electrons that attach to dissolved oxygen in the cells, creating radical ions. Those ions interrupt biochemical reactions which cells rely on for communication and basic life functions. In this way, we can target and kill very specific bacterial cells that cause illnesses.

The superbug threat

Antibiotics are used not just to treat active bacterial infections; they are also routinely given to patients undergoing surgery and to people with compromised immune systems from diseases like HIV and cancer.

Bacteria that are resistant to more than one antibiotic drug—or “superbugs,” as they are commonly called—infect more than 2 million Americans a year and kill 23,000 of them. Globally, they kill more than 700,000 people each year.

Projections by a United Kingdom government research panel suggest that, if unchecked, superbugs could kill more than 10 million people each year by 2050. That would far outpace all other major causes of death—including diabetes, cancer, diarrhea and road accidents. The economic cost is estimated at $100 trillion by 2050.

Focusing on a target

There are other nanoscale medicines for fighting infectious bacteria. When exposed to light, they heat up, killing all cells around them—not just the disease-causing ones. They, therefore, require special tools such as proteins or antibodies that selectively stick to desired cell types, to deliver them to very specific locations. That, in turn, requires the ability to accurately identify target cells.

Our method is an improvement because it allows more specific targeting of cells to be treated. Quantum dots with different sizes and electrical properties can help create different disruptive ions. That can allow doctors to choose disruptors to kill invading bacteria without harming nearby healthy tissue.

The activated quantum dots upset the balance of chemical processes, called “reduction-oxidation” (“redox” for short) in disease-causing bacteria in order to kill them.

Using this method and only a normal light bulb, we were able to eliminate a broad range of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The bacteria were provided to us in the form of actual clinical samples from the University of Colorado School of Medicine. They included some of the most dangerous drug-resistant infections: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and Salmonella typhimurium; multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli; and carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli.

We were also able to make nanoparticles with different reactions to light, including having no response or even improving cellular reproduction. Increasing the growth of superbugs is not desirable, but this discovery may allow us encourage the growth of useful bacteria, such as in bioreactors, which can help manufacture of biofuels and antibiotic drugs.

Taking the next steps

So far our work has been in test tubes in controlled labs; our next step is to study this technique in animals. If successful, this technology could boost the fight against multi-drug-resistant bacteria in the short term and well out into the future.

It might, for example, spur the creation of a new class of light-activated drugs, lead to development of special fabrics with LED lights for phototherapy, and even form the basis of self-disinfecting surfaces and medical equipment.

And while the bacteria will continue to evolve to seek survival, our ability to control the specific reaction of the quantum dots, once activated, could let us move more quickly in this fight where defeat is not an option.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026.

Oral Wegovy pills were approved by the Food and Drug Administration in December 2025 and became available for purchase in the U.S. in January 2026. Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

Despite the effectiveness of GLP-1 drugs for weight loss, there is still no replacement for healthy lifestyle patterns, including regular exercise.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit

Anxious young woman in the rain.Photo credit  Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Woman takes notes.Photo credit

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.