Have you ever wondered how you just seem to know how far you have to go to your destination? Or maybe you were on a road trip and thought to yourself, "only about 275 miles to go," only to pass a sign that lists your destination as 272 miles away. Well, it turns out there's a reason for these occurrences and also for why you inherently remember how to get somewhere.

Scientists at Scotland's University of St. Andrews located the "mileage clock" inside a brain after recording the brain activity of rats running in a square around the perimeter of their cage. This allowed them to find the part of the brain responsible for this very important task. When the scientists changed up the rats path, that sense failed them and they wandered around lost and confused.

The brains of the rats behaved like an odometer, ticking off the steps and miles. When the researchers put people in a similar situation, they behaved exactly like the rats, suggesting humans have this same feature in their brains, the study, published by Current Biology, revealed.

"Imagine walking between your kitchen and living room," Professor James Ainge, who led the study, told BBC News. "[These cells] are in the part of the brain that provides that inner map – the ability to put yourself in the environment in your mind."

"The fact that humans and rats show the same type of errors in distance estimation in different environments gives us confidence that the brain mechanisms are the same in both species," Ainge said.

Alzheimer's connection

This is the first study to reveal the ticking of "grid cells" in the brain that are responsible for correctly assessing the distance we've traveled. These cells are one of the first areas that Alzheimer's disease affects, making this a potentially useful early detection tool.

"People have already created [diagnostic] games that you can play on your phone, for example, to test navigation," Ainge said. "We'd be really interested in trying something similar, but specifically looking at distance estimation."

When this process backfires, such as in darkness or fog, it becomes difficult to gauge how far we've gone. In the study, when the scientists changed the shape the rats had to run in, their behavior became erratic and the rats grew agitated while attempting to figure out the maze.

"It's fascinating," Ainge added. "They seem to show this sort of chronic underestimation. There's something about the fact that the signal isn't regular that means they stop too soon."

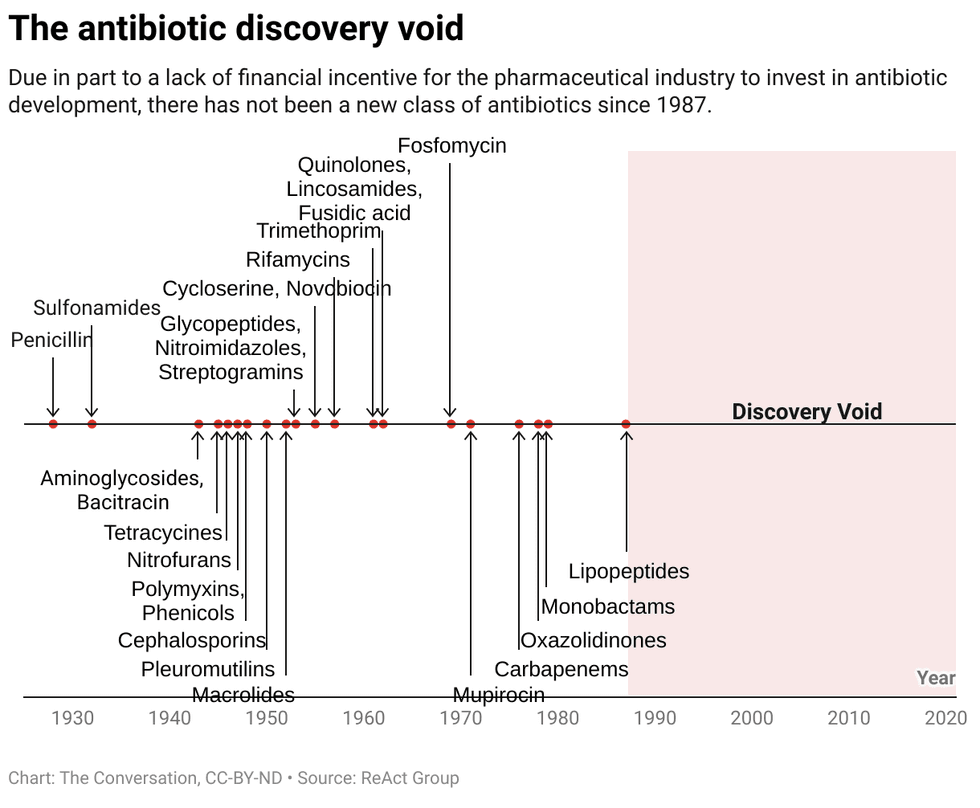

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Raccoons know how to get around.

Raccoons know how to get around. The dexterity of raccoon hands enables their humanlike escapades.

The dexterity of raccoon hands enables their humanlike escapades. The dexterity of raccoon hands enables their humanlike escapades.

The dexterity of raccoon hands enables their humanlike escapades.

A doctor looks at brain imaging scansCanva

A doctor looks at brain imaging scansCanva