Alan Gandelman is a 34-year-old organic vegetable farmer in upstate New York. He’s of two minds about the effect of patents on farming. On the one hand, he understands their value. The previous owner of the land on which Gandelman's’s Main Street Farms is located spent 50 years breeding new varieties of cabbage there. He eventually patented a strain, sold his land, and retired.

“I totally understand and appreciate how much work he put into breeding his line of really good, disease-resistant, fast-growing, good-scoring cabbage that now a lot of the world eats,” Gandelman told me on a recent afternoon. “Because he did put in all that work for literally his whole life, he got paid for it.”

Not everything is this clearly reasonable, Gandelman admits. In the past, he did some work with a university raising black soldier fly larvae. An Ohio-based company is now looking to patent a similar process, with an eye to mass-producing them as food for fish farms.

“They're basically just maggots,” he tells me, with a laugh at the idea of patenting them.

Ever since the Supreme Court ruled in 1980’s Diamond v. Chakrabarty that you could patent living things (in that case, a modified bacterium that could help in oil-spill cleanup), patents have played an increasingly large and contentious role in farming. Their impact on commodity crops has been well documented over the past several years, with big corporations patenting seed varieties and aggressively enforcing their patents by taking small farmers to court. Monsanto—which currently has more than 6,000 patents in the US alone—has engaged in a litigious quest to protect its Roundup Ready corn so well known that the company has been forced to add a section to its otherwise anodyne Q&A titled, “Why Does Monsanto Sue Farmers Who Save Seeds?”

Lesser known is the impact of patenting of farming methods. Historically, these types of patents have been common in high-tech and relatively complex fields like industrial milking and aquaponics. Just one company, industrial dairy farm company Lely, has almost a dozen patents related to the setup and operation of the robotic milking of dairy cows. Now, patented methods (and products) are coming to the field of farming something a bit lower-tech: insects like maggots and crickets.

One of the biggest companies in this space is Tiny Farms, a California-based consultancy trying to become a one-stop shop for people looking to move into cricket farming.

“What we're trying to do is give people as close to a turnkey package as we can,” its co-founder Andrew Brentano told me on a recent evening. And Tiny Farms is hoping to have this farm-in-a-box patented, with patents focusing on “specific equipment that solve problems on a farm that haven't been solved before.”

What does a would-be cricket rancher get in Tiny Farms’ kit? Since his patents are pending, Brentano is hesitant to give full exact details, but confirmed that it will contain physical materials and instructions, as well as training and an “information infrastructure.” It will also include one common feature of cricket farms of all sizes: cut-up egg cartons.

“We've tried dozens of different things for them to live on, and they just love those egg cartons,” Brentano said.

Little bugs, big business

Companies like Tiny Farms are moving into insect farming because the planet is staring down the barrel of a few really bad, really unavoidable changes to the way we eat. And they’re going to be happening pretty soon.

As the developing world has gotten richer in the past 30 years, its per capita consumption of meat has doubled. This has driven the yearly average per capita consumption of meat to more than 90 pounds for each of the world’s 7 billion people, according to a 2015 report from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. And it’s projected to grow to almost 100 pounds per person, per year, by 2030. Of course, the number of people is growing too. The United Nations predicts global population will reach 8.5 billion by 2030, and a staggering 9.7 billion by 2050. All this food is going to have to come from an even smaller patch of the planet; One recent study estimates that the Earth has lost one-third of its farmable land in the last 40 years. In short, more people are eating more food that will have to come from less and less land.

One of the major ways the world’s food policy thinkers believe we as a species will be meeting our nutritional needs in the coming century is by eating bugs (they are also projected to be a major source of animal feed). Bugs are a surprisingly environmentally friendly, resource-light, nutrition-heavy food source. One popular farm bug is the cricket, not least because of this stat: one pound of beef needs 25 pounds of feed, while one pound of crickets needs only two pounds of feed. There’s also the fact that 100 grams of ground cricket “flour” (really closer to a protein powder) has more than twice as much protein than the same amount of steak. Today, you can buy cricket tortilla chips, cricket bitters, cricket protein bars, and a lot more.

The problem is that cricket farming is still in its infancy. While many people are interested—Brentano says Tiny Farms has been contacted by hundreds of eager cricket ranchers—the output is still relatively small. That’s the reason a pound of cricket flour costs $35. There’s not a good, regulated way to farm them so the output meets the demand. To meet the world’s needs, the sector will need to ramp up dramatically, and soon.

That’s what companies like Tiny Farms are banking on. They hope to protect this market niche they’ve identified with their patents and build a large, sustainable business.

“They spent money creating a new product, and they applied to protect their product, and they got it,” said Michael Timmons, a professor in Cornell’s Department of Biological and Environmental Engineering focusing on entrepreneurship, speaking generally about agricultural patent holders. “Is there anything wrong with that? It's the capitalist society we live in.”

Patents exist in the first place for exactly this reason: Since innovators can profit from their ideas, they’re encouraged to innovate. Still, something niggles at your sense of justice when you think of patenting living things. While it’s true that companies and scientists spend years developing new strains of crops, selective breeding has produced essentially every animal and plant we know today, from roses to dachshunds. What if you got a cease-and-desist order in the mail every time your dog had puppies?

The issue in the current system is enforcement, said Timmons. On the one hand, broad patents can be essentially useless for their holders if they don’t stand up to litigation.

“You can file anything, basically, but it only has value if you can defend it in court,” he said. On the other hand, patent abuse can be a real problem, particularly “where a company files a patent, but it's something that might be considered common knowledge, but they have the legal muscle to prevent you from (challenging) it, even though it's common knowledge.”

Patents in farming, Gandelman said, “weren't intentionally created this way, but they end up favoring people who have a lot of money and a lot of reach. It's basically an abuse of power, but they are kind of acting within the law.”

Even Tiny Farms, which is currently building a business in part by relying on patents, isn’t much of a fan of our current system.

“The patenting of methods, is it real? Is it valid? I don't really know,” said Brentano. “I don't personally like it. Earlier, we had an open-source project, but unless you have very specific market conditions, it doesn't really work. So we've reverted to a more regular patent and license model. We'd love to go back to open source if the market changes … We feel cognizant of the catch-22, where you wish it didn't work that way, but if these are the rules everyone plays by, I guess we will too.”

Gandelman was living in India during Monsanto’s contentious battle to overturn its laws that prevented the patenting of any biological materials. “There was a lot of global pressure from Monsanto to patent seed in India,” he said. “Farmers there were committing suicide. They were afraid that if this went through, they would at the mercy of giant agribusinesses from around the world.”

The unfortunate reality of patent law is that it’s up to each patent holder how they want to enforce them. Do they simply use it to support an active business or do they chase down anyone they think might be violating it, tying up honest farmers in court for years? The decision is theirs, but it impacts all of us, especially as the world’s needs for as yet unorganized farming practices like insects, where patents are still up for grabs, grows.

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?

What foods would you pick without diet culture telling you what to do?  Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Flexibility can help you adapt to – and enjoy – different food situations.

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

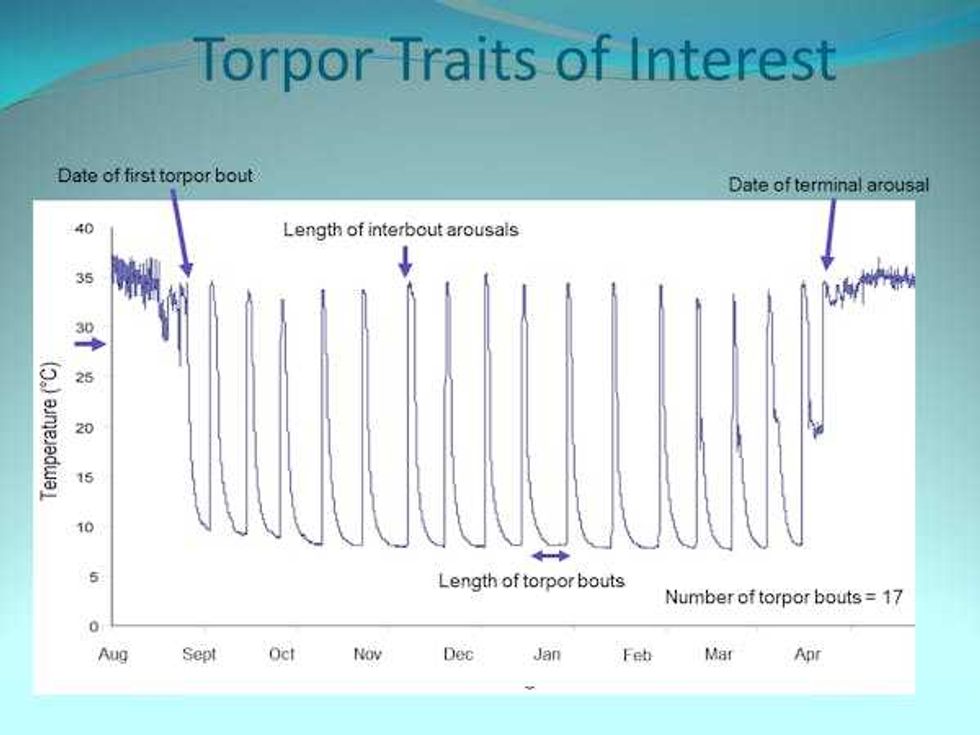

Female groundhog emerging from her burrow in late January.Stam Zervanos, Author provided This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

This Maine groundhog had 17 torpor bouts where body temperature went up and down.Stam Zervanos, Author provided Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

Male groundhog (on the right) greeting a female groundhog for the first time after they emerge from their separate burrows.Stam Zervanos, Author provided

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva

A beluga whale frolicking in the oceanCanva  A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A beluga whale pops up from the waterCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva

A woman sits in a new car at a dealershipCanva GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

GIf from 'Pretty Woman' of Roberts saying "BIg mistake. Big. Huge." via

People voting. Photo credit:

People voting. Photo credit:  Young women rally. Photo credit:

Young women rally. Photo credit:  Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/

Tressie McMillan Cottom.Tressie McMillan Cottom/