Studying tectonic plates helps geologists understand a landform’s geological history, locate rare metals, and predict future natural processes. In 2023, geologists from Utrecht University in the Netherlands made a stunning discovery while studying the Pacific plate. Suzanna van de Lagemaat, the team's lead geologist, found a massive, previously unknown tectonic plate once a quarter the size of the Pacific Ocean. They named it the "Pontus plate." A detailed study of this discovery was published in the Gondwana Research Journal.

The search for Pontus began unknowingly over a decade ago when researchers from the same university found fragments of old tectonic plates deep in Earth’s mantle using seismic tomography. This technique uses seismic waves from earthquakes or explosions to create images of Earth’s interior. Suzanna conducted detailed investigations of the mountain belts in Japan, Borneo, the Philippines, New Guinea, and New Zealand to reconstruct the lost plates, according to a university press release.

This decade-old study showed that a large subduction zone must have run through the western paleo-Pacific Ocean, which separated the known Pacific plates in the east from the hypothetical Pontus plate in the west. “11 years ago, we thought that the remnants of Pontus might lie in northern Japan, but we’d since refuted that theory”, explained Douwe van Hinsbergen, Suzanna’s PhD supervisor. “It was only after Suzanna had systematically reconstructed half of the ‘Ring of Fire’ mountain belts from Japan, through New Guinea, to New Zealand that the proposed Pontus plate revealed itself, and it included the rocks we studied on Borneo,” per the university press release.

Suzanna studied the planet’s most complicated tectonic plate region, the area around the Philippines. “The Philippines is located at a complex junction of different plate systems. The region almost entirely consists of oceanic crust, but some pieces are raised above sea level, and show rocks of very different ages.” Using geological data, Suzanna reconstructed the movements of the current plates in the region between Japan and New Zealand. The area was so large that she concluded that the old plates must have disappeared in the current western Pacific region.

The team also conducted fieldwork on northern Borneo, where they found “the most important piece of the puzzle.” Then they looked at the magnetic properties of rocks to learn when and where they formed, Suzanna told Live Science. The magnetic field surrounding Earth gets "locked in" within rocks when they form, and that magnetic field varies by latitude.

The magnetic field study of the plate rocks revealed clues to a previously unknown plate. “We thought we were dealing with relicts of a lost plate that we already knew about. But our magnetic lab research on those rocks indicated that our finds were originally from much farther north, and had to be remnants of a different, previously unknown plate,” said Suzanna. But there was another surprise waiting for her to unfold.

"It's surprising to find remnants of a plate that we just didn't know about at all," Suzanna told Live Science. Her discovery revealed that the relicts of Pontus are not only located in northern Borneo, but also on Palawan, an island in the Western Philippines, and in the South China Sea, indicating that what’s currently left is part of that old gigantic tectonic plate. This enormous plate originally stretched from southern Japan to New Zealand and must have existed for at least 150 million years. Over the years, it shrank and shrank, getting pushed under the Australian plate to the south and China to the north, disappearing 20 million years ago.

This article originally appeared 5 months ago.

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva

A road near equatorial Atlantic OceanCanva Waves crash against rocksCanva

Waves crash against rocksCanva

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:

Older woman drinking coffee and looking out the window.Photo credit:  An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:

An older woman meditates in a park.Photo credit:  Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:

Father and Daughter pose for a family picture.Photo credit:  Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

Woman receives a vaccine shot.Photo credit:

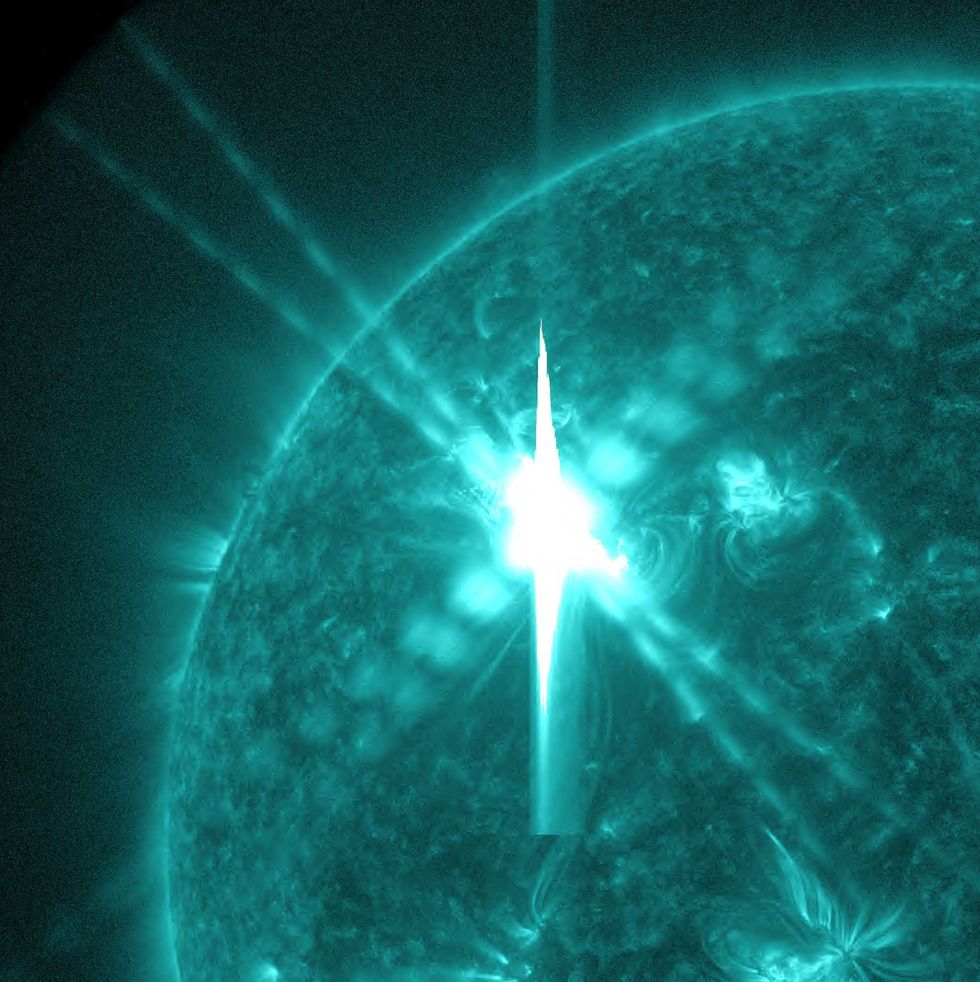

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Image artifacts (diffraction spikes and vertical streaks) appearing in a CCD image of a major solar flare due to the excess incident radiation

Brady Feigl in February 2019.

Brady Feigl in February 2019.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.

Yonaguni Monument, as seen from the south of the formation.