I spoke in January 2026 with 150 high school students about career options. After explaining my own career as a professor of education, health and behavior, I asked the students a simple question: Would you want to be a teacher?

“Why in the world would I want to be a teacher?” one female student said.

“My aunt is a teacher and she works all the time … no thanks,” a male student added.

Several students said it felt like teachers were doing everything: from teaching lessons and helping students through personal struggles to managing class disruptions and constantly adjusting to whatever else the day brought. Students also mentioned hearing teachers talk openly about low pay or feeling a lack of respect from students and others.

These students’ observations align with national trends. While nearly 20% of college freshmen said in 1970 that they were interested in a teaching career, less than 5% said the same in 2020, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Many teachers report low levels of job satisfaction, and 52% polled by Pew in 2024 said they would not advise young adults to become teachers.

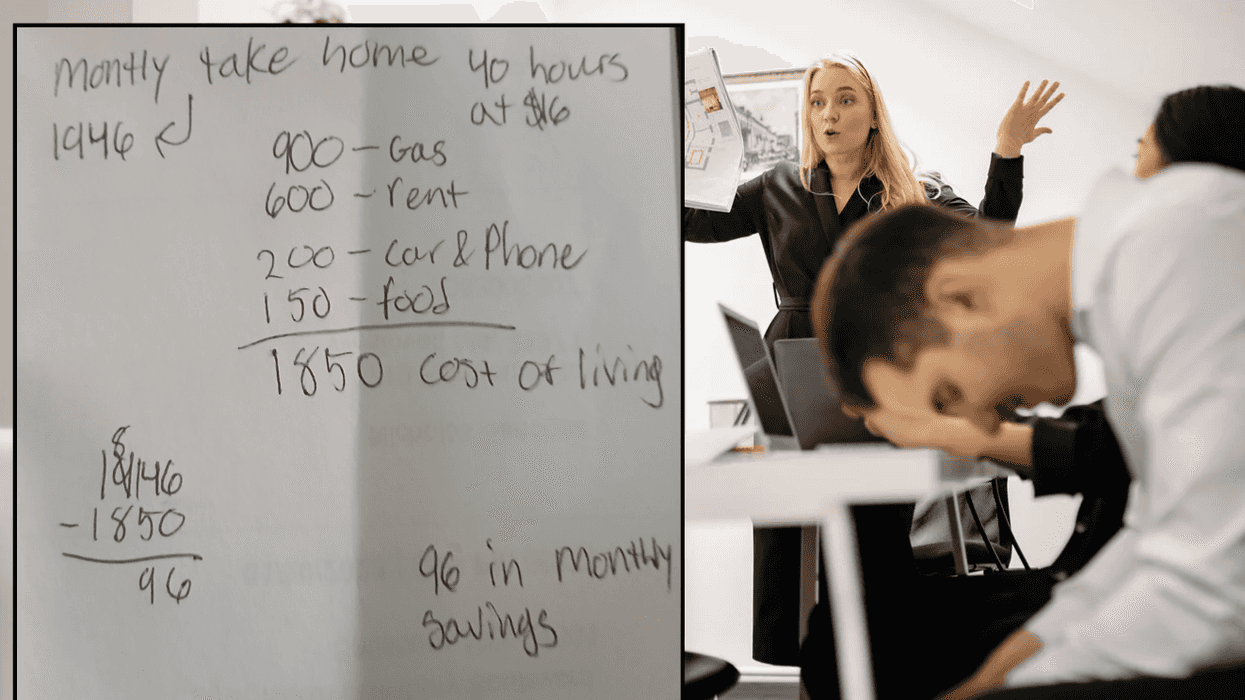

Teacher pay penalty

Education researchers and labor analysts have documented that teachers earn less than other people who also have college degrees.

This difference in pay is sometimes called the teacher pay penalty. This gap has widened over the past few decades.

In 2024 the teacher pay penalty reached its highest recorded level, with teachers earning roughly 73 cents for every dollar earned by other college graduates.

Average annual public teacher salaries recently have ranged from about US$53,507 in Mississippi and $53,098 in Florida to more than $95,160 in California and $95,615 in New York.

Nationwide, teachers on average earn about $72,030 per year.

National analyses show that teaching has steadily lost ground in wage competitiveness compared with other college-educated professionals over the past few decades.

Even as some states have enacted modest teacher salary increases year over year, these wide disparities persist.

Expanding expectations, rising strain

Teaching once centered primarily on academic instruction. Particularly through much of the 20th century, teachers’ roles were largely defined by planning lessons, instructing on different subjects and assessing student learning.

In addition to teaching core subjects, many teachers are now often expected to help support students’ social and emotional development, address complex behavioral challenges, respond to crises that spill into classrooms, such as students physically fighting, and manage substantial paperwork and administrative tasks.

The COVID-19 pandemic intensified many of these responsibilities, as teachers navigated remote instruction and students’ heightened mental health needs.

At the same time, concerns about school safety, including the reality of school shootings and other kinds of violence, have added another layer to teachers’ emotional strain and required vigilance.

Teachers are far more likely than other college-educated professionals to report frequent job-related stress and burnout.

Job available

Approximately 50% of all public school leaders reported in October 2024 that they feel their school is understaffed. And 20% of public school leaders reported teacher vacancies during that same time period.

In January 2022, shortly after the pandemic, more than 20% of public schools reported at least 5% of their teaching positions were vacant that month. Approximately 51% of schools reported that resignations were the cause of these vacancies.

A 2025 national teacher shortage overview estimates that roughly 1 in 8 teaching positions nationwide are either unfilled or staffed by someone not fully certified for the assignment, meaning a teacher working outside their licensed subject area or grade level, for example.

When positions are filled this way, the classroom will still have a teacher present, but not necessarily one formally prepared to teach a specific subject or group of students. This can result in greater reliance on substitutes or increased class sizes for remaining staff.

When teaching became women’s work

History helps explain why teaching looks – and pays – the way it does today.

In the early 1800s, teaching was a predominantly male profession.

But as the U.S. industrialized in the late 1800s and early 1900s, higher-paying jobs in business and manufacturing drew many men away from classrooms.

For many women at the time, teaching offered one of the few respectable professional careers available. It provided steady income and a measure of independence when many other professions were closed to them.

Labor force participation for women expanded significantly during the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, as legal and social barriers began to fall. Yet the pay and public standing of teaching does not seem to have risen at the same pace.

By the early 1900s, women made up about 70% of teachers. In 2024, 77% of teachers were women.

Nationwide, the gender wage gap has narrowed in the past few decades. Still, women in the U.S. earn an average 85% of what men make.

Who will teach the next generation?

Each year, more than 80,000 new teachers step into classrooms. But the overall pipeline has narrowed since the early 2010s, with enrollment at teacher preparation programs declining sharply and only partially rebounding in recent years.

Today’s students are coming of age in a landscape where teaching competes with many other college-degree professions that may offer higher pay, more predictable hours or clearer career advancement.

College students are often weighing financial security, mental health and long-term sustainability as they imagine their future.

Research consistently shows that compensation, working conditions and professional support play a central role in job retention. When those elements erode, so too does workforce stability.

Stability is the key as students are evaluating teaching – not as a calling, but as a potential career within a competitive labor market.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. You can read it here.

A coupe on a romantic dateCanva

A coupe on a romantic dateCanva

A woman swims in the oceanCanva

A woman swims in the oceanCanva A happy-looking dolphin popping out of the waterCanva

A happy-looking dolphin popping out of the waterCanva

When mayors come together, they often find they face common problems in their cities. Gathered here, from left, are Jerry Dyer of Fresno, Calif., John Ewing Jr. of Omaha, Neb., and David Holt of Oklahoma City.

When mayors come together, they often find they face common problems in their cities. Gathered here, from left, are Jerry Dyer of Fresno, Calif., John Ewing Jr. of Omaha, Neb., and David Holt of Oklahoma City. Mayors can find themselves caught up in national debates, as did Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey over the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement policies in his city.

Mayors can find themselves caught up in national debates, as did Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey over the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement policies in his city.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021.

Volunteers at the St. Francis Inn pray together before serving a meal on July 19, 2021. Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

Police close down a section of Kensington Avenue to clear a homeless encampment on May 8, 2024.

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

A woman scrolls through a dating appCanva

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.

Openly choosing the one you like best can help break down stigmas.