When graphic designer Kate Bingaman-Burt noticed her credit card debt piling up a few years back, she knew exactly what she had to do to get out of this hole she’d dug for herself: draw her statements.

To her, this was the ultimate form of punishment (she hated drawing)—and just enough negative reinforcement to pay off her debt quickly.

But it also forced Bingaman-Burt to slow down and think about the choices she was making with her money. Here, she discusses why she made this conscious decision to bare her financial failures to the world and what she learned from being so open about the “D” word—debt.

Back in 2002, I was a designer and a salesperson for a gift company in Omaha, Nebraska. My job was to design things that people didn’t necessarily need: disposable goods, like gourmet foods, candles, and drink mixes. When I was traveling all over the country for trade shows, I witnessed consumerism on display in a very intense way.

I saw a physical fight break out between adults who were trying to place Beanie Baby orders at a show in D.C. This was when Beanie Babies were super popular, and it disgusted me to see grown people push each other out of the way so they could get their fall orders in.

Around that time, I was fascinated by the artist Ed Ruscha. In the 1960s he had a series of photo projects that existed on rule systems and rule structures. Basically, he would come up with this idea, and then set this rule system around it. So I made rules for myself to follow, execute, and repeat—and to not overthink, but to just make.

In 2004, I decided to draw my credit card statements. I created this rule for myself, mostly because I didn't feel comfortable drawing. And I was very ashamed about my debt. Plus, my shaky hand was the total opposite of the machine-generated statements I received every month.

I had a pit in my stomach when I started doing the credit card project because I was so embarrassed by my $24,000 credit card debt. It wasn't like I had made big purchases. It was just little things over time that kind of add up. And suddenly, I’m like, ‘Oh, I don't know how to manage my money.’

In a way, drawing the statements was like writing I will not be stupid with money over and over and over again.

I didn't love that project, but what I do love is moving closer to achieving a goal. When I saw the drawings pile up, I felt a sense of satisfaction. Every time I got a statement, I would try to double up on the minimum payments to pay it off faster.

I also sold my drawings on my website, Obsessive Consumption, to subsidize the payments. I had six different cards that needed to be paid off, so I put each illustration up for the minimum monthly payment of each statement. It varied from statement to statement. Some credit cards had a minimum of $144, others were just $24.

I was drawing in a pretty public way, and I wasn't sure how people were going to react. Some folks were like, ‘That’s so dumb, why would you want to do that?’ But a lot more people would tell me about their stressful credit card debt. I ended up being a credit card priest, basically. I was suddenly the confessional outlet. It was very emotional.

A lot of people contacted me just to tell me they had a lot of guilt about money—that they had X amount of debt and that they were not telling anyone and that they felt trapped. Usually, women would email me and tell me they were too afraid to tell their partners they had secret credit cards.

I don't think that they were necessarily looking to me for solutions, they were just looking to me for a sympathetic ear. It was more like, ‘Listen, this is my deal.’ There wasn't an expectation of a response. It was almost like they were practicing how they were either going to tell someone or how they were going to take steps to get out of debt. They didn't feel like they could tell their friends because they were worried about being judged. And I was this person who had no right to judge because I was screwed up, too.

Out of all the projects I've done surrounding personal consumption, that one was the most emotional. There was guilt and fear and shame.

I felt like I was coming from a place of extreme privilege because I had a job. I was able to pay off my debt and I had time to make drawings of it! For a lot of the people, that wasn't the case. About two years into that project, in 2006, I decided that I wanted to draw something else other than my dumb credit card statements—I wanted to draw my purchases.

I was really interested in the history and stories behind objects and the emotions connected to stuff. This process of documentation really made me slow down on more frivolous purchases and think about what I was buying. A lot of that was just about being aware of what we are consuming, both tangibly and online.

Initially, I thought this would be a fairly clinical process, but it surprisingly led to long, sometimes intense conversations—the catalyst being things. That’s what got me hooked: the strangely quick human connection over objects.

Today with social media, everybody loves to tell everyone else all of the things—but money hasn't quite gotten there yet. It’s still kind of a taboo subject. I feel like the more transparent we are with that, the easier it will be to tackle these issues.

As told to Jackie Lam

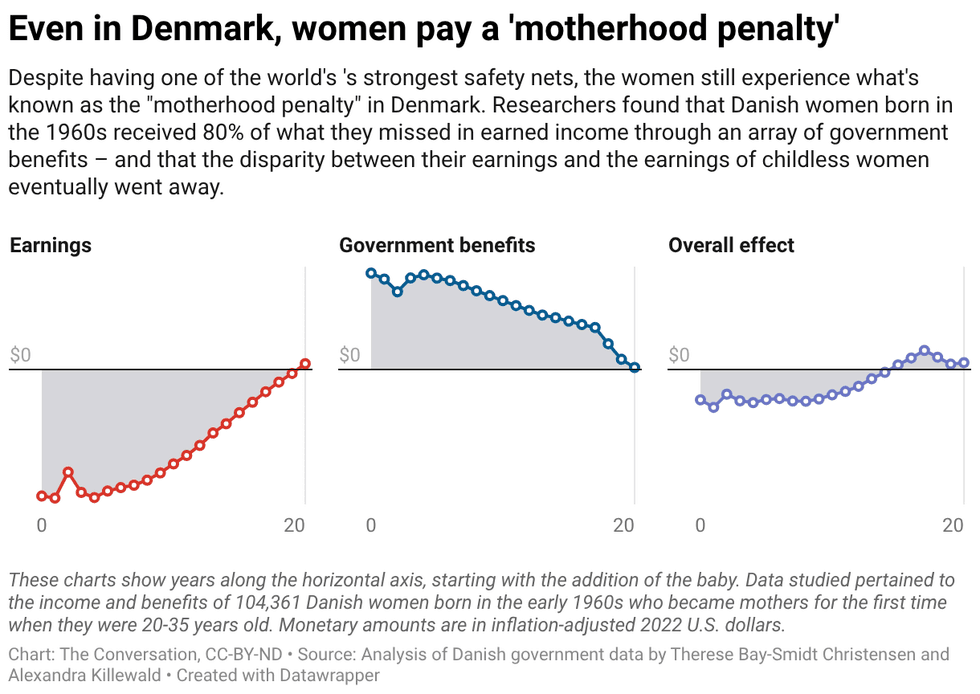

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents.

As mayor of Stockton, Calif., Michael Tubbs ran a pioneering program that provided a basic income to a limited number of residents. Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.

Martin Luther King Jr. believed Americans of different racial backgrounds could coalesce around shared economic interests.