If you’ve ever attended a party where everyone is dressed in fancy clothes and sipping champagne carried around on platters, there’s a decent chance you were either A) doing well in life and feeling perfectly at ease in this luxurious setting or B) suffering a severe case of imposter syndrome and wondering if everyone at said event was thinking to themselves, "Who invited this person?" Of course, I’m basing that hypothetical purely on my own concept of social status, not any concrete data. But a fascinating new study suggests a strong correlation between one’s self-perception of "class" and their ability to perceive other people’s emotions.

As the study’s authors noted in Scientific Reports, they found "a negative relationship between individuals’ social status and empathic accuracy," noting, "[S]pecifically, those with lower social status were better at identifying emotions in other individuals." Perhaps if you felt out of place at the aforementioned fancy luncheon, you would have been more likely to spot someone else with that same struggle.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Emotional perception and "upward social mobility"

The researchers open their abstract by recognizing the power of emotional perception on "upward social mobility," both personally and professionally—it seems logical that if you can hone in on how people feel, you’re more likely to succeed in life. However, that theory appears to contradict prior research suggesting that individuals of "lower social status" can better perceive people’s emotions. They set out to learn more about this conundrum: Are these social cognitive skills inherent to people of a "lower" social status, or does that ability help one advance their social status?

To find out, they recruited 1,197 American adults—average age 38, 50% female, 50% Democrats, and 74% white—to participate in a paid study via the tech company Prolific. The participants were asked to complete two tasks related to "emotion perception": the Geneva Emotion Recognition Test (focused on assessing emotions in individuals) and the Ensemble Emotion Task (groups). They also provided demographic information and answered questions relating to both subjective and objective social status.

The subjective status was determined via the MacArthur Subjective Social Status Scale, the Subjective Social Class measure, and the Subjective SES Scale. The first is particularly intriguing: The paper notes that "participants were shown a ladder in which the highest rungs represent the people who are best off (e.g., most money, education, career respect) and the lowest rungs those who are worst off and then indicated the rung that best represents where they are on that ladder (from 1 to 10)."

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Social status "across the lifespan"

As mentioned above, the researchers found that individuals with lower social status were more adept at identifying others' emotions. But they also drew further conclusions—considering changes in social status "across the lifespan" to observe "a negative relationship between the change in social status and emotion perception." (They did, however, highlight the need for additional research in this area.) Additionally, the "emotional status of people in a group was not predicted by social status, with the observed relationships only having marginal effects that were generally in the opposite direction."

Recent research also suggests interesting connections between intelligence and empathy. A paper published in the journal Intelligence, outlining the results of two studies focused on adults in the U.K., found that individuals who scored high on cognitive abilities (such as problem-solving, memory, and critical thinking) scored lower on moral foundations. This data, the authors wrote, challenges "existing theories relating to intelligence and moral intuitions," though "causal direction remains uncertain." Let's all do our best to show empathy, regardless of how smart—or high-class—we are.

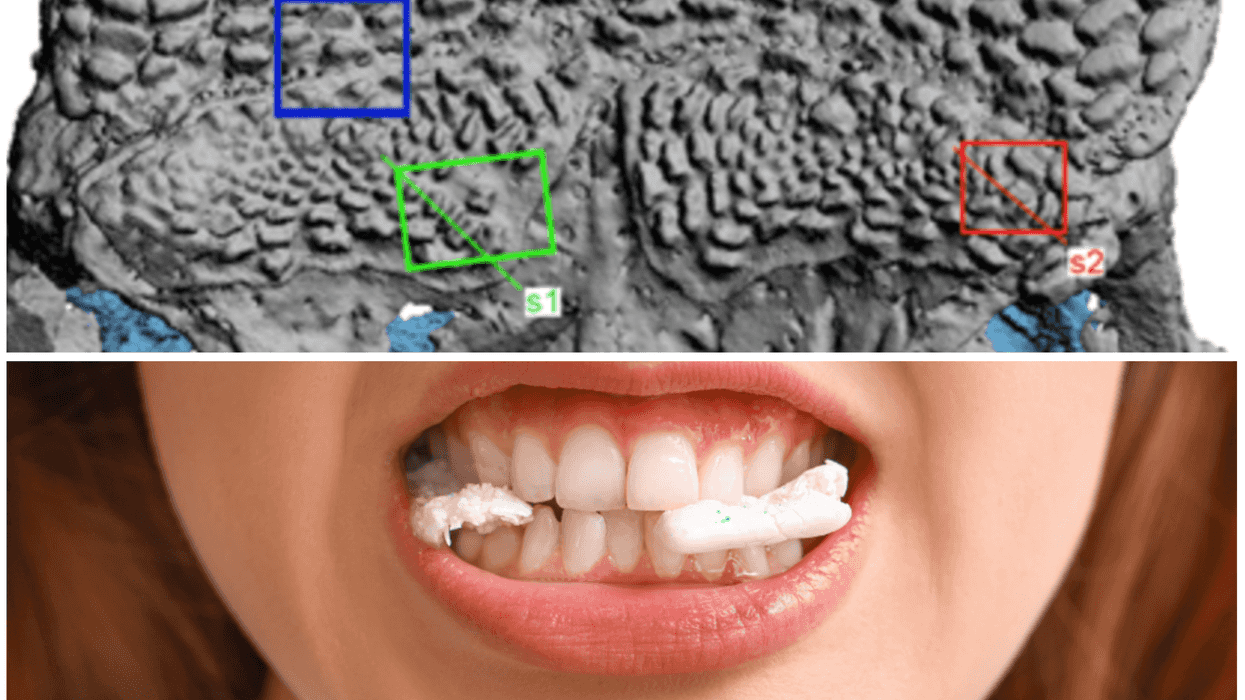

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:

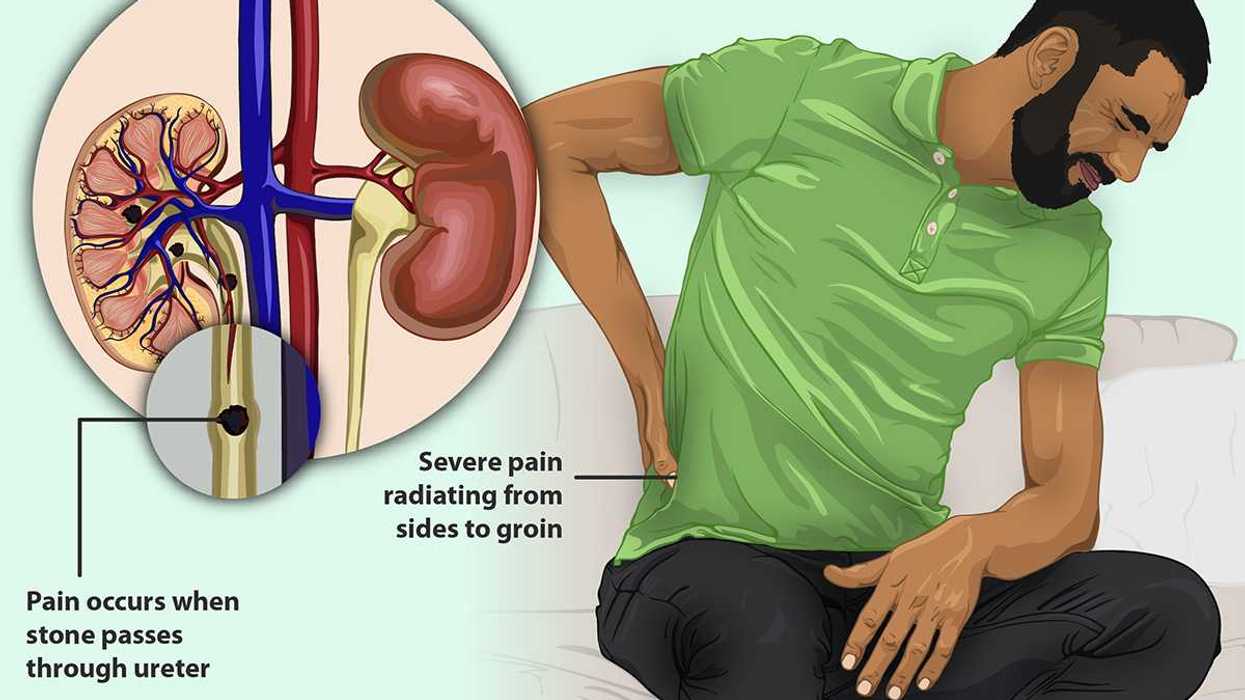

Left: A robotic arm. Right: Rice grains.Photo credit:  A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

A diagram on kidney stones.myupchar/

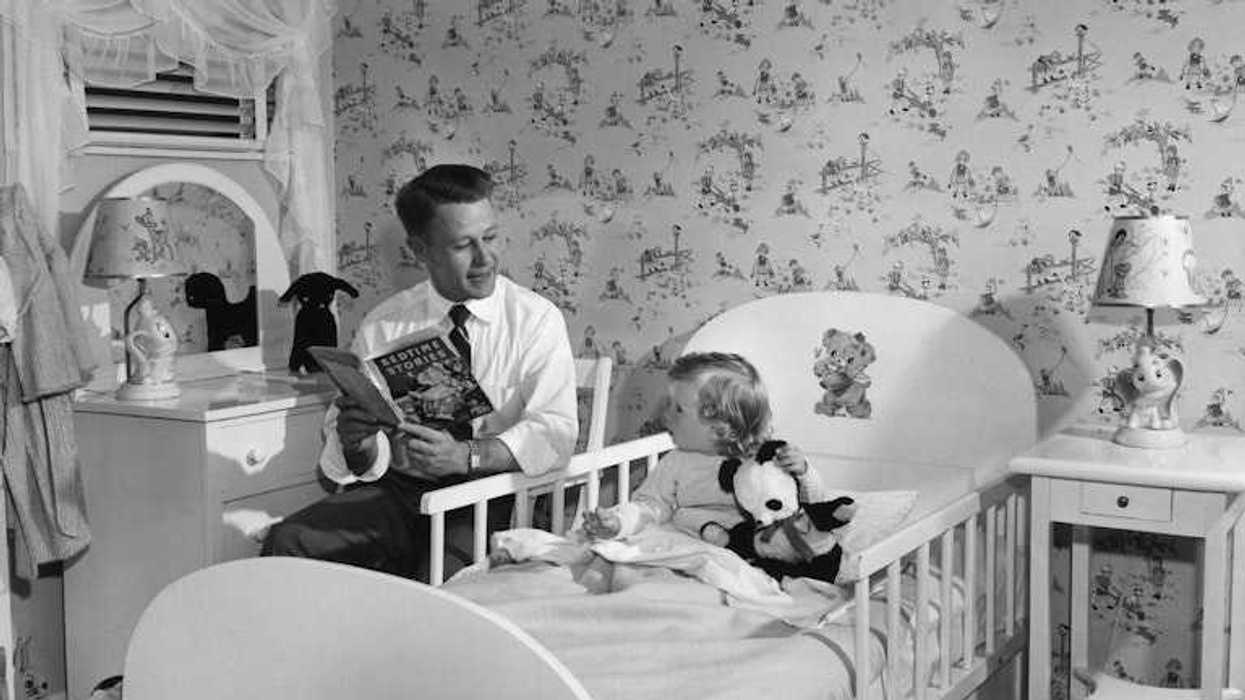

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025.

Christy Lam-Julian, a mother in Pinole, Calif., reads to her son in April 2025. Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.

Children who read bedtime stories with their parents are likely to benefit from a boost in creativity – especially if they consider questions about the books.