Chronic heavy alcohol drinking can lead to a problem that we scientists call alcohol use disorder, which most people call alcohol abuse or alcoholism. Whatever name you use, it is a severe issue that affects millions of people and their families and causes economic burdens to our society.

Quitting alcohol, like quitting any drug, is hard to do. One reason may be that heavy drinking can actually change the brain. Our research team at Texas A&M University Health Science Center has found that alcohol changes the way information is processed through specific types of neurons in the brain, encouraging the brain to crave more alcohol. Over time, the more you drink, the more striking the change.

In recent research we identified a way to mitigate these changes and reduce the desire to drink using a genetically engineered virus.

Alcohol changes your brain

Alcohol use disorders include alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence, and can be thought of as an addiction. Addiction is a chronic brain disease. It causes abnormalities in the connections between neurons.

[quote position="right" is_quote="true"]Alcohol changes the way information is processed through specific types of neurons, encouraging the brain to crave more of it.[/quote]

Heavy alcohol use can cause changes in a region of the brain, called the striatum. This part of the brain processes all sensory information (what we see and what we hear, for instance), and sends out orders to control motivational or motor behavior.

The striatum, which is located in the forebrain, is a major target for addictive drugs and alcohol. Drug and alcohol intake can profoundly increase the level of dopamine, a neurotransmitter associated with pleasure and motivation, in the striatum.

The neurons in the striatum have higher densities of dopamine receptors as compared to neurons in other parts of the brain. As a result, striatal neurons are more susceptible to changes in dopamine levels.

There are two main types of neurons in the striatum: D1 and D2. While both receive sensory information from other parts of the brain, they have nearly opposite functions.

D1-neurons control “go” actions, which encourage behavior. D2-neurons, on the other hand, control “no-go” actions, which inhibit behavior. Think of D1-neurons like a green traffic light and D2-neurons like a red traffic light.

Dopamine affects these neurons in different ways. It promotes D1-neuron activity, turning the green light on, and suppresses D2-neuron function, turning the red light off. As a result, dopamine promotes “go” and inhibits “no-go” actions on reward behavior.

Alcohol, especially excessive amounts, can hijack this reward system because it increases dopamine levels in the striatum. As a result, your green traffic light is constantly switched on, and the red traffic light doesn’t light up to tell you to stop. This is why heavy alcohol use pushes you to drink to excess more and more.

These brain changes last a very long time. But can they be mitigated? That’s what we want to find out.

Can we mitigate these changes?

We started by presenting mice with two bottles, one containing water and the other containing 20 percent alcohol by volume, mixed with drinking water. The bottle containing alcohol was available every other day, and the mice could freely decide which to drink from. Gradually, most of animals developed a drinking habit.

We then used a process called viral mediated gene transfer to manipulate the “go” or “no-go” neurons in mice that had developed a drinking habit.

[quote position="left" is_quote="true"]Employing viruses to deliver specific genes into neurons is already in practice for disorders such as Parkinson’s disease.[/quote]

Mice were infected with a genetically engineered virus that delivers a gene into the “go” or “no-go” neurons. That gene then drives the neurons to express a specific protein.

After the protein is expressed, we injected the mice with a chemical that recognizes and binds to it. This binding can inhibit or promote activity in these neurons, letting us turn the green light off (by inhibiting “go” neurons) or turn the red light (by exciting “no-go” neurons) back on.

Then we measured how much alcohol the mice were consuming after being “infected,” and compared it with what they were drinking before.

We found that either inhibiting the “go” neurons or turning on the “no-go” neurons successfully reduced alcohol drinking levels and preference for alcohol in the “alcoholic” mice.

In another experiment in this study, we found that directly delivering a drug that excites the “no-go” neuron into the striatum can also reduce alcohol consumption. Conversely, in a previous experiment we found that directly delivering a drug that inhibits the “go” neuron has the same effect. Both results may help the development of clinical treatment for alcoholism.

What does this mean for treatment?

Most people with an alcohol use disorder can benefit from treatment, which can include a combination of medication, counseling and support groups. Although medications, such as Naltrexone, to help people stop drinking can be effective, none of them can accurately target the specific neurons or circuits that are responsible for alcohol consumption.

Employing viruses to deliver specific genes into neurons has been for disorders such as Parkinson’s disease in humans. But while we’ve demonstrated that this process can reduce the desire to drink in mice, we’re not yet at the point of using the same method in humans.

Our finding provides insight for clinical treatment in humans in the future, but using a virus to treat alcoholism in humans is probably still a long way off.

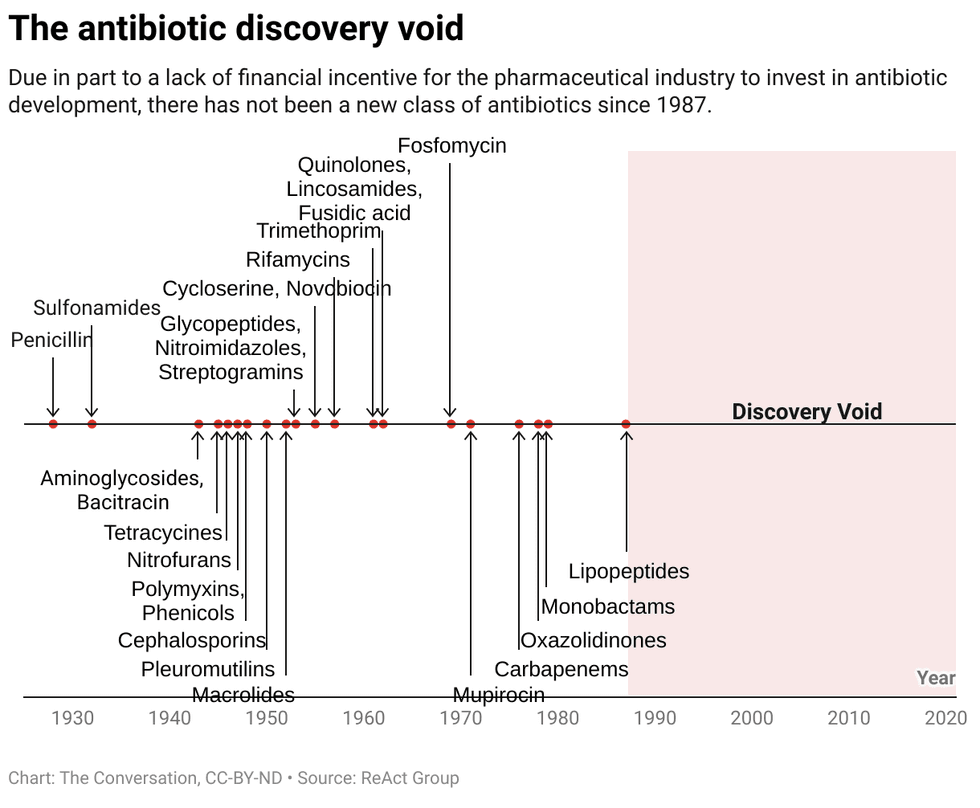

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:  Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:

Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:  Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit:

Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit: