In fifth-grade parent-teacher conferences, I would have been unanimously labeled a "good kid": straight As, lots of friends, zero troublemaking. But I already felt a creeping anxiety, a sense of dread and general displacement—from my conservative small town town, from even my own family—that I couldn’t properly diagnose at age 10. I felt…weird, but I didn’t know why. Music became the escape hatch: the classic rock emerging from my parents’ tape deck (The Beatles, The Doors, Yes), the alternative rock soaked in via MTV and my older brothers’ CD collection (Smashing Pumpkins, Weezer, Stone Temple Pilots). But the most profound breakthrough— the moment that instantly made me feel, "A-ha, I’m not alone out here, and there’s a lot of magical weirdness in the world of adults"—was first encountering Radiohead’s "Paranoid Android" one ordinary weeknight on our rec-room TV.

It wasn’t even the song’s darkly comedic, NSFW animated video. It was the music itself—a thunderstorm of an arrangement that careened wildly between sweet falsetto and bratty punk snarl, between a steady 4/4 time and a jolting 7/8, between quiet acoustic picking and triple-guitar chaos and choral-rock splendor. As a sponge-like pre-teen with still-malleable taste, the game was over—I’d never heard anything like this. Decades later, I still haven’t. Back then, soon after that first encounter, armed with recently acquired birthday cash, I excitedly ventured to my local Walmart and bought a copy of the full album, 1997’s OK Computer. Back home, I popped the CD into my portable player, closed my bedroom door, and strapped on my massive headphones. In what became my marquee "important album" ritual—even through my adulthood as a music critic—I turned off the lights, closed my eyes, and pressed play. I’ve been chasing the thrill of that first listen ever since.

- YouTube www.youtube.com

"Paranoid Android" may have been OK Computer’s dynamic centerpiece, but the rest was equally cinematic: the slow-burn drama of "Exit Music (For a Film)," the twinkling psychedelia of "Subterranean Homesick Alien," the lush and multilayered balladry of "Let Down," the chillingly distorted atmospheres of "Climbing Up the Walls." The album continued Radiohead’s gradual metamorphosis of critical acclaim—from being widely dismissed as one-hit-wonders (Pablo Honey, home to the self-grunge anthem "Creep") to earning a baseline of respect (their more ambitious second LP, The Bends) to, finally, being anointed as the Pink Floyd of their generation. (It’s not just journalists either. OK Computer is currently ranked No. 2 all time on the fan site RateYourMusic, trailing only Kendrick Lamar’s 2015 hip-hop masterpiece, To Pimp a Butterfly.)

This was a pivotal moment in the maturation of popular music: With its use of dissonant string sections and processed drum sounds and glimmering keyboards, OK Computer gave "modern rock" bands more permission to experiment and push themselves. It was also a pivotal moment in my musical journey—from here on, I routinely sought out weirder and weirder bands, eventually becoming a devoted fan of art-rock and prog-rock and jazz-fusion. This was the gateway that opened 100 other gateways. Even still, in terms of emotional pull and pure imagination, no other album has ever drawn me in quite like this one. But why is that? Is OK Computer that incredible, or is my brain just clinging to the dopamine surge of my formative years? Do I only love it so much because, back then, I needed it so much?

Various studies support the theory that we reach a certain plateau in terms of music discovery—one that researcher Daniel Parris labeled "music paralysis." A 2018 New York Times exploration of Spotify data found that our most-played songs are often those released during our teenager years, particularly between ages 13 and 16. In 2021, a YouGov poll asked people which decade was the best for music, and there was a clear link between age and chosen decade. (For example, the highest percentage of Gen Z respondents (17%) picked the 2010s; for Millennials, it was the 1990s (23%); Gen X selected the 1980s (38%); Boomers went with the 1970s (38%), and the Silent Generation chose the '50s or earlier (39%).

- YouTube www.youtube.com

Experts say this is no accident. Dr. Nicole Anders, a Licensed Clinical Psychologist and instructor/counselor with Trauma Recovery Yoga (T.R.Y.) in Las Vegas, tells GOOD that the teenage brain is "literally hard at work doing two things: pruning and wiring."

"Your neural pathways are laying down and fortifying new connections on an almost hourly basis. It’s no surprise that, if a song or repeated stimulation is emotionally charged or novel, it’s going to be tagged in the brain as cement," she says. "The music you blast on your way to the park with your bike or sob to as you stare at your bedroom ceiling when your heart is broken…that music got associated with a chemical cocktail of hormones and memory consolidation and the imprint was made. That song will always feel carved into your identity. Like 'learn every lyric 20 years later and have the tune blast through your body decades after' kind of deep."

However, Anders says this whole thing is, naturally, a bit more complicated than one paragraph can explore. "To be fair, I think the notion that adults no longer listen to new music because they are too busy to find it (or take the time to get into it) is only part of the picture," she adds. "It makes far more sense to me to think of how patterns of immersion change over time. A teenager may listen to a record for 150 minutes, repeat lyrics, and learn the chord changes, but an adult may only squeeze in 15 minutes to a new song while on a commute. It is the exposure difference (tenfold) that consolidates a deeper connection when young. It is not that the adult brain is averse to newer music, but the conditions to form an intense connection are not present."

- YouTube www.youtube.com

In fact, she says that what people describe as "music paralysis" is more like "preference consolidation." She continues, "After a certain age (around 20 or so), the brain has evolved a more discriminating process with tagging emotional connection. Songs will get processed but not imprinted. The same goes for food, art, even friendships in many cases. Novelty windows are narrow and shorter in adulthood. Here is the part that makes it so difficult for new music to catch up: the songs from adolescence are connected with the context of that first heartbreak, that one-night drive, and a particular smell. New tracks just can’t compete with a full-body flashback."

Maybe the best music is the stuff that really endures on that physical level—it broke your brain when you were 12, and it still gives you goosebumps at 45. As I flash back to that sheltered fifth-grader escaping a mundane and confusing world by savoring "Karma Police" through his (Radio)headphones, I’m reminded of how this album has stuck to me like chewed-up gum under a bleacher. It was there in high school, for so many aimless windows-down drives around my small town. It was there in college, when I wrote an essay about it for an English course. And it’s here with me today, the placid guitar tones of "The Tourist" swimming out as I write this final sentence.

A high school senior shows how to unlock a magnetic pouch that holds her smartphone at University High School Charter in Los Angeles in March 2025.

A high school senior shows how to unlock a magnetic pouch that holds her smartphone at University High School Charter in Los Angeles in March 2025. An eighth grader unlocks her cellphone from a pouch at Mark Twain Middle School in Alexandria, Va., in March 2025.

An eighth grader unlocks her cellphone from a pouch at Mark Twain Middle School in Alexandria, Va., in March 2025.

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

Gif of a mom wiping her child's dirty face via

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva

A woman holds a family member's hand in the hospitalCanva A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

A bird flying across the sky under the sunCanva

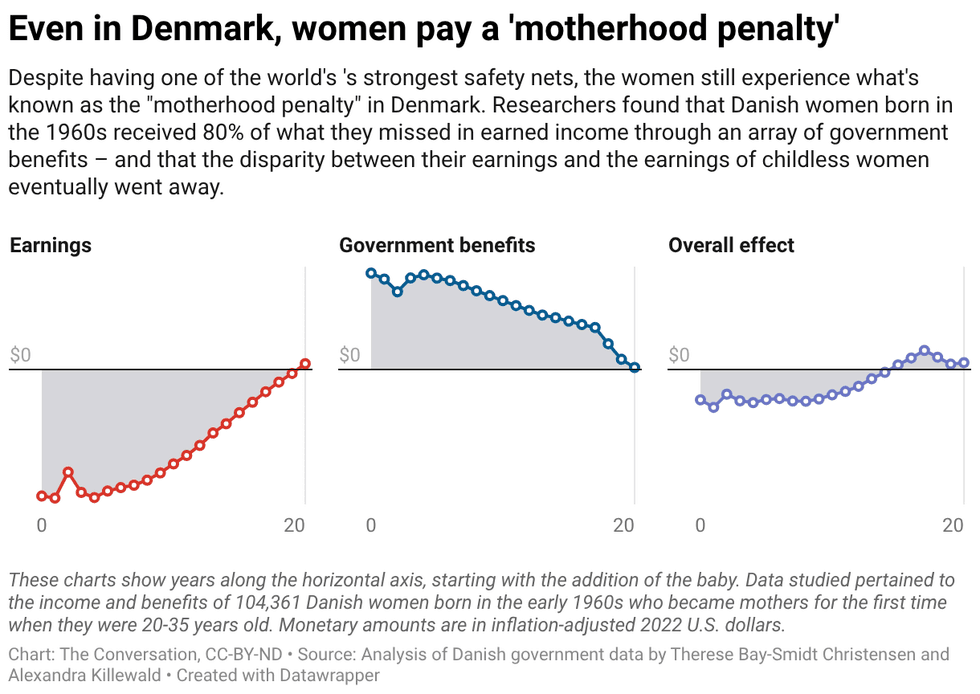

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

The ‘motherhood penalty’ is largest in the first year after a mom’s first birth or adoption.

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/

(LEFT) Film premiere at ArcLight Theatre Hollywood; (RIGHT) LaNasa signing autographs at TIFF.thepaparazzigamer/  Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Radical acceptance.Photo credit:

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/

Scott Galloway in Barcelona in 2025.Photo credit: Xuthoria/  Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:

Resting in the shade of a tree.Photo credit:  Two people thinking.Photo credit:

Two people thinking.Photo credit: