If you haven’t heard of the Daily Mile yet, your time has come. Now taking place in 3,600 primary schools each day in 35 countries around the world, it takes children outside during normal lesson time to run or walk laps of the playground for 15 minutes. The ones who run cover around a mile each day.

The initiative has an endearing back story. It was developed six years ago by St. Ninian's Primary School in Stirling in central Scotland after children and teachers felt the pupils needed to be in better physical condition.

Other schools quickly realized the value, and it started to spread. It is now happening in around half of the Scottish primaries and a quarter of those in England; while schools have also got on board everywhere from the U.S. to the United Arab Emirates to Nepal to Australia.

With all this enthusiasm, it was time for researchers to ask the obvious question: Is it really worth doing?

We have been part of a collaboration between the universities of Stirling and Edinburgh that has just published the first results.

Inactive children

The backdrop to The Daily Mile is a global childhood physical activity crisis. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that children get at least 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise each day – the kind that gets them out of breath. They should also do some resistance exercise each week to strengthen their muscles. Despite this, fewer than 40% of children achieve these recommended levels.

Independent of the exercise you do, too much time spent sitting or lying down (while awake) is also bad for your health. The recommended maximum is two hours of TV per day and limited sitting the rest of the time. Again, fewer than 40% of children around the world achieve this. The healthiest people do high amounts of moderate/vigorous exercise and spend low amounts of time sitting/reclining.

The number of overweight and obese children has increased dramatically in recent years, and lack of exercise and too much sitting around will be part of the reason. Overweight kids are at higher risk of diabetes, strokes, and heart disease in later years, so this directly affects both their quality of life and potentially their lifespan.

Equally alarmingly, children’s physical fitness has significantly declined since at least the 1980s. They can’t run as far without stopping as their parents could.

What we found

Governments have introduced various research-led interventions to combat these threats – increasing the intensity of physical education classes, for example – but with mixed success. There are basically two hurdles: any intervention needs to be something children will keep doing, and it has to improve their health.

The Daily Mile has the attraction of being both simple and designed not by researchers but by a teacher and some children. The fact that so many schools are participating suggests that children keep doing it. So how about the effect on their health?

Children do The Daily Mile at whatever time of day their teacher chooses. Typically, they do a mixture of walking and running, doing laps of a school pitch, or playground in normal school clothes and shoes. Importantly, each child sets their own pace and is free to talk to other pupils or teachers as they go.

We compared 391 children ages 4 to 12 years old in two local schools over the course of an academic year. One school was about to introduce The Daily Mile while the other was not.

At the start and end of the study, we measured each child in the following ways: fitness (by bleep test), physical activity levels, and sedentary time (both by accelerometer belts), and body fat (by skin fold calipers). (We looked at skin folds and not weight because body mass index is not great at measuring “fatness” in this age group: the results get warped by the weight of bones developing as kids get taller.)

The children in the school that introduced the Daily Mile increased their moderate/vigorous physical activity by nine minutes per day (around 15%), and cut their sedentary time by 18 minutes per day (around 6%). They saw a 40-meter increase (circa 5%) in how far they could run, while their skin folds reduced by an average of 1.4mm or 4%.

Some question the impact of The Daily Mile on lesson time, but there’s little reason for this. We have previously shown in almost 12,000 children that a single bout of similar exercise made them more awake, increased their attention and verbal memory, and improved their feelings of well-being. We have also heard anecdotal claims about other benefits such as better sleep and diet.

In short, our results suggest The Daily Mile is definitely worthwhile. In the future, we need to expand our research to understand whether it can work in different educational settings, such as high schools, and whether it works equally well for pupils from different backgrounds.

![]() For the moment, The Daily Mile can certainly be part of the solution to child health and well-being. Look out for it: it could be here to stay.

For the moment, The Daily Mile can certainly be part of the solution to child health and well-being. Look out for it: it could be here to stay.

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva

A woman relaxes with a book at homeCanva An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva

An eviction notice is being attached to a doorCanva Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

Gif of Kristen Bell saying 'Ya basic!' via

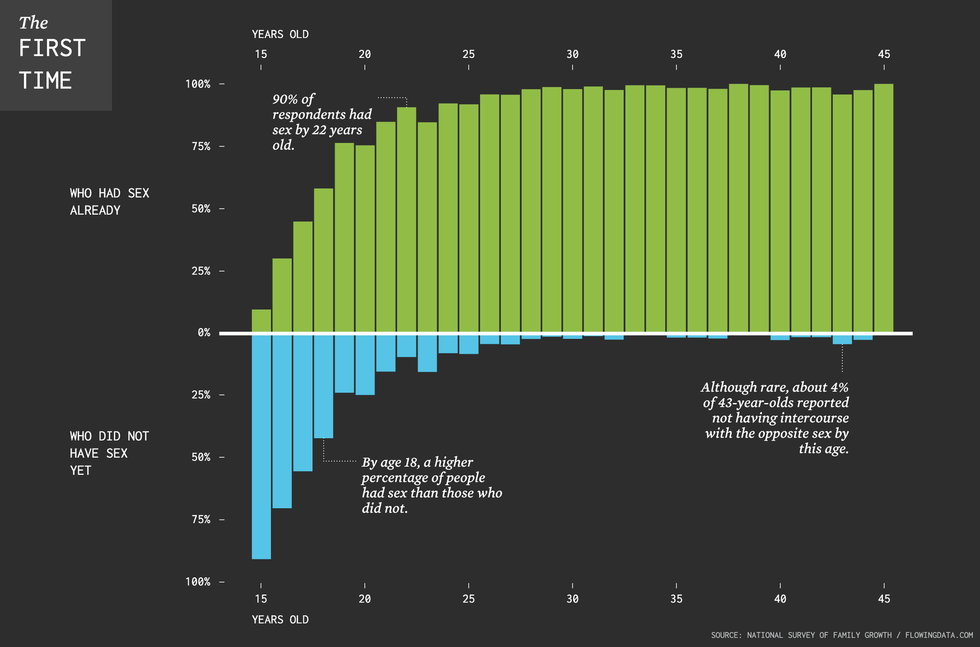

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex.

The chart illustrates that between ages 16 and 20, roughly half the population loses their virginity. By age 22, 90% of the population has had sex. A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

A group of young people hold their phonesCanva

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/

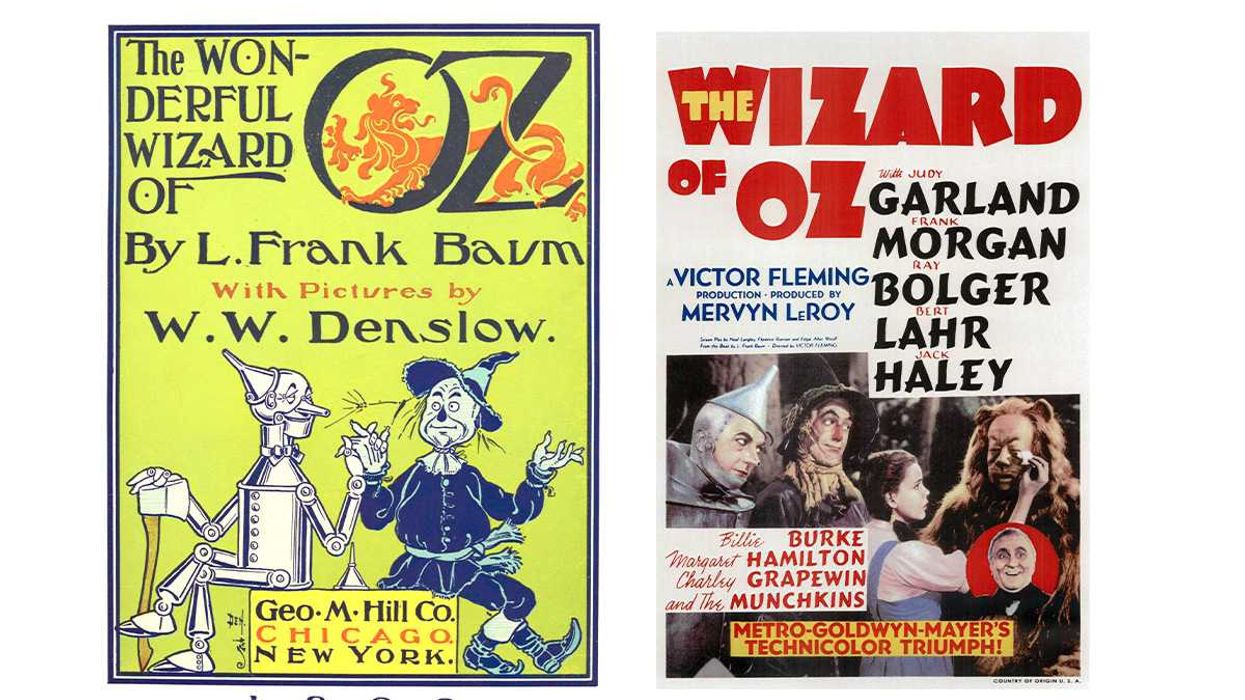

(LEFT) Judy Garland as Dorothy Gale and (RIGHT) Ray Bolger as Scarecrow from "The Wizard of OZ"CBS/  (LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

(LEFT) The Wonderful Wizard of Oz children's novel and (RIGHT) The Wizard of Oz movie poster.William Wallace Denslow/

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva

A frustrated woman at a car dealershipCanva Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

Bee Arthur gif asking "What do you want from me?" via

A couple on a lunch dateCanva

A couple on a lunch dateCanva Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

Gif of Obama saying "Man, that's shady" via

Elegance in red.Photo credit:

Elegance in red.Photo credit:  An older woman shows off some bling.Photo credit:

An older woman shows off some bling.Photo credit:  A woman enjoys a beautiful day. Photo credit:

A woman enjoys a beautiful day. Photo credit: