By age 18, my knees hurt. I didn’t know why, and they didn’t hurt a lot, but they did hurt a bit most of the time. As someone who took a lot of dance classes and played my share of netball, it was annoying, but not something I thought much about. After all, I reckoned, bad knees run in my family. But by age 20, the pain had gone from a bit annoying to definitely annoying. I decided, for the first time, to see a doctor about it.

She was a brisk woman with close-cropped grey hair, who glanced at me and told me my knee pain was due to early-onset arthritis as a result of my being overweight. My blood tests were negative for rheumatoid arthritis — but that didn’t matter, she told me. The only way to stop my pain from getting worse was by losing weight. So with the resigned sigh of anyone who has grown up fat, I accepted my fate. I was arthritic, at 20.

By 22, things were worse. My knees had gone from hurting a bit most of the time to spontaneously collapsing in blinding pain while I was doing innocuous activities like walking down the street. I went back to the doctor — a different one, because I just saw whoever was available at the student clinic. He asked me about my pre-existing medical conditions. I explained that my arthritis was a result of being overweight. He looked at me incredulously. “That’s not a thing.” No one gets non-rheumatoid arthritis in their twenties as a result of being overweight, he explained.

Instead, he decided we should figure out exactly why my knees were spontaneously collapsing. He sent me for an MRI, and I had a consultation with a specialist surgeon. “Patellae chondromalacia,” the surgeon declared. He showed me the shadows on my scan, which indicated rough patches on my knee caps. It was probably hereditary, exacerbated by my weight.

“Ok,” I said. “So what can I do about it?”

“You’re just going to have to manage the pain,” he explained. “And once it gets to be too much, you’re going to need your knees replaced. And that will probably be before you’re 30.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]I had eight years before I turned 30. It felt a bit like a death sentence.[/quote]

Resigned, I accepted my diagnosis. I said goodbye to yoga and dance, which aggravated the condition, and started wondering about how much two new knees might cost, and how I’d get around on crutches. I had eight years before I turned 30. It felt a bit like a death sentence.

At 24, my new housemate decided she was joining our local gym, and in a moment of optimism, I decided to go with her. This gym offered a free short session with one of their personal trainers to help newbies learn the ropes. “I’ll put you with Hao,” the receptionist said. “He’s got a physio background; he’s good with injuries.”

Hao was intimidating — really tall, super buff, thick Chinese accent that was hard to understand at first. “It says here you’ve got an injury,” he told me. “What is it?”

“I’ve got patellae chondromalacia in both knees,” I replied. “It’s-“

“Oh that,” he said, interrupting me. “I can fix that.”

What?

Hao explained to me that what I had was a pretty standard sporting injury that is usually treated successfully using exercise — a fact that none of my doctors had mentioned. I’d probably injured myself as a result of all that dance and netball I did as a teenager, and it might have been exacerbated by my family history of dodgy knees. It’s normally caught early and treated early — it’s very rare for it to get to the point of causing knees to collapse, but that can happen in serious cases with no treatment. “Work with me for 10 sessions,” said Hao. “If you don’t notice a difference, I’ll give you your money back.”

Well, after 10 sessions I noticed a pretty significant difference. After six months, the pain that had plagued me for six years was entirely gone.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]When doctors looked at me, they didn’t see a girl who danced, cycled, and played team sports. They saw a fat girl .[/quote]

I can’t help but think that there’s a whole lot of physical pain I could have avoided if any of the medical professionals I saw had considered the fact that I might have a sporting injury. And I can’t help but wonder if the reason they didn’t has to do with my weight.

When doctors looked at me, they didn’t see a girl who danced, cycled, and played team sports. They saw a fat girl — and they based their diagnosis on stereotypes about what that meant. I’m 29 now, and my knees no longer hurt. I don’t need to have them replaced — but if I’d listened to the weight-prejudiced opinions of my doctors, I might have.

This story is hardly unique.

Research shows that doctors have less respect for patients with higher body-mass indexes, which can lower the quality of care those patients receive. As one study put it:

“Many health care providers hold strong negative attitudes and stereotypes about people with obesity. There is considerable evidence that such attitudes influence person-perceptions, judgment, interpersonal behavior, and decision-making. These attitudes may impact the care they provide.”

Troublingly, many of the ideas that doctors have about fat patients aren’t even grounded in medical fact. Indeed, too often it’s forgotten that the science around weight loss and health isn’t all that settled. Does excess weight cause you to live a shorter life? Maybe, maybe not. Countless studies by BMI category have found that overweight people actually have lower rates of all-cause mortality than normal weight people.

Some researchers think that if you adjust for the increased risks caused by weight cycling (aka. yo-yo dieting) and dangerous weight-loss drugs, you’d find the same mortality rates for normal, overweight, and obese people — yes, even very obese people. And even without the adjustments, the increased risk for very obese people is only small — not the “you’ll be dead before you’re 30” nonsense often pedaled by purveyors of weight-loss surgeries.

What about serious disease? There’s certainly a correlation between being overweight and some diseases, but multiple studies suggest that the weight might actually be a symptom rather than a cause.

Then there’s the idea that excess tissue “strains” the body. Eminent obesity researcher Dr. Paul Ernsberger has been quoted as saying, “The idea that fat strains the heart has no scientific basis. As far as I can tell, the idea comes from diet books, not scientific books . . . Unfortunately, some doctors read diet books.”

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]So why, then, do doctors insist on prescribing diets and weight loss as a treatment for anything and everything?[/quote]

What about dieting? Well, there actually is some scientific consensus there : Diets don’t lead to lasting weight loss—not even if you call them lifestyle changes. After an extensive metastudy of diet and weight loss studies, Dr Traci Mann concluded, “The benefits of dieting are simply too small and the potential harms of dieting are too large for it to be recommended as a safe and effective treatment for obesity.”

So why, then, do doctors insist on prescribing diets and weight loss as a treatment for anything and everything?

Sarah, 29 from Newcastle, Australia, had the misfortune of breaking both legs as a teenager, the result of a freak accident involving her legs falling asleep and then getting twisted to the point of breaking. Not long after learning how to walk again, she was involved in a serious car accident that left her with further damage to her legs. “I’m accident-prone,” she laughs. The multiple injuries have left Sarah with a build up of scar tissue that can make walking painful. But when she went to the doctor, her pain was blamed on her weight.

“My weight is a factor in the healing process,” she says, “But it wasn’t the cause of my injuries — and I’ve got police reports, x-rays, and specialist reports to prove it.”

Sarah changed doctors recently, and her new doctor decided to do a full medical history, checking the notes from all the physicians Sarah has seen. What she found shocked her. “She said there’s no record of my injuries with most of my previous doctors,” Sarah said. “They all had written that my leg pain was caused solely by my weight, and that meant I wasn’t getting any useful treatment for the pain. They just told me to diet.” Sarah’s new doctor promptly started her on a physical treatment plan designed for someone with compound injuries and severe internal scarring.

The difference has been immediate.

“Within two weeks I could walk nearly five kilometers. Before I started the treatment, I could only manage one kilometer or less before my knees were so swollen and painful that I couldn’t keep going,” said Sarah. “Getting actual treatment for my injuries, rather than just being told to lose weight and see what happens, has changed everything.”

Just to be clear, I’m not saying that eating healthily and exercising aren’t good for you. The problem is when doctors prescribe diets and weight loss to patients without fully considering their symptoms and other treatment options.

Stigmatization may also, problematically, stop fat people from seeking out medical care in the first place.

“I just don’t go to the doctor,” says Anita, a 28-year-old advertising executive. The last time Anita saw a doctor, it was a routine visit to discuss vaccinations and antimalarial medication for an upcoming overseas trip. The doctor prescribed the vaccines and asked a nurse to administer the jabs. It was the nurse who decided Anita had diabetes — without having spoken to her, or seeing anything pertaining to her medical history.

“He kept saying I would get a discount on the vaccines if I registered my diabetes,” Anita explained. “I haven’t got diabetes, but he wouldn’t listen. His whole attitude was like, ‘You know you’re fat, right?’ Um, yeah, I’ve noticed that, actually. Just give me the jabs.” The experience was pretty upsetting, and left Anita firmer in her resolve to avoid doctors wherever possible.

Still, Anita, Sarah, and I are relatively lucky; our experiences have caused us pain and humiliation, but no permanent damage. This is not true for everyone.

First Do No Harm is a website that chronicles the experiences of fat people with medical professionals — and it’s filled with harrowing stories.

One woman lost a lot of weight suddenly and was praised for it — with doctors missing the fact that it was a sign of the cancer that shortly killed her.

A man vomited constantly due to multiple sclerosis, but instead of viewing that as a medical red flag, doctors simply celebrated the 120-pound weight loss it caused. The vomiting led to permanent nerve damage, back pain, and tooth decay.

A woman had an emergency doctor declare that she didn’t need treatment for abdominal swelling after a serious car accident because she was just fat. She nearly died.

A woman went years just being told to lose weight to address her ongoing, multiple health problems. It turns out she has a rare neurological disorder; the diagnosis delay has led to permanent brain damage.

There’s another trove of awful stories on fat prejudice here. And of course Google’s got plenty more.

[quote position="full" is_quote="true"]Hormonal problems? Lose weight. Broken finger? Lose weight. Migraines? Lose weight.[/quote]

A consistent narrative runs throughout these stories. Hormonal problems? Lose weight. Broken finger? Lose weight. Migraines? Lose weight. Losing weight is the consistent — sometimes only — treatment offered for every ailment imaginable.

For many, changing the narrative around weight is literally a matter of life or death. So what can be done to address the problem?

The good news is that there’s some recognition within the medical profession that this is a serious issue which must be addressed. It’s been noted that medical students don’t receive nearly enough training on obesity, and efforts are beginning to try to change that. Researchers are also working on empathy programs and raising awareness about the impact of implicit bias against patients. All of this is a promising start.

At the same time, we can all become our own health advocates. If you’re a fat person, or someone you care about is a fat person, you can develop your critical thinking skills and challenge the classic “just lose weight” prescription if it doesn’t seem to fit the symptoms.

This isn’t easy. There’s an implicit power imbalance between patient and doctor that makes challenging their statements very difficult. By working to become experts on our own health and our own situation, we stand a better chance of being able to call out something that doesn’t feel right.

Doctors are highly educated people, but they’re subject to the same biases as the rest of us, and many of them don’t stay up to date with the latest research. That’s not good enough. If obesity really is a major health concern, it’s essential that doctors stay educated on recent studies and metastudies that look at how to get the best outcomes for fat patients. If doctors really do care about their patients, they need to start looking at the overall picture of a person’s health, not simply the size of their body.

Most of all, doctors need to stop prescribing a treatment that’s proven not to work for conditions that don’t warrant that treatment in the first place.

The medical profession needs to step up. It needs to accept that diets aren’t the universal treatment option for fat people. It needs to accept that fatness isn’t the universal cause of ill health in fat people. It needs to engage with the very real damage caused by its attitudes toward fat people, and with the substandard care delivered to many people as a result of their size.

It’s not exaggerating to say that lives depend on it.

This piece is published in partnership with The Establishment.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

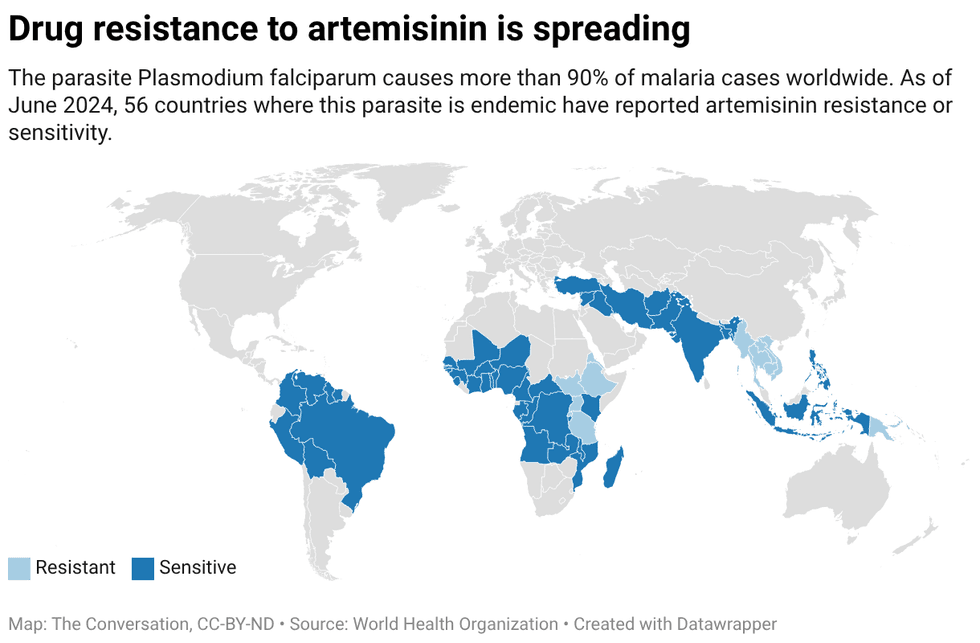

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

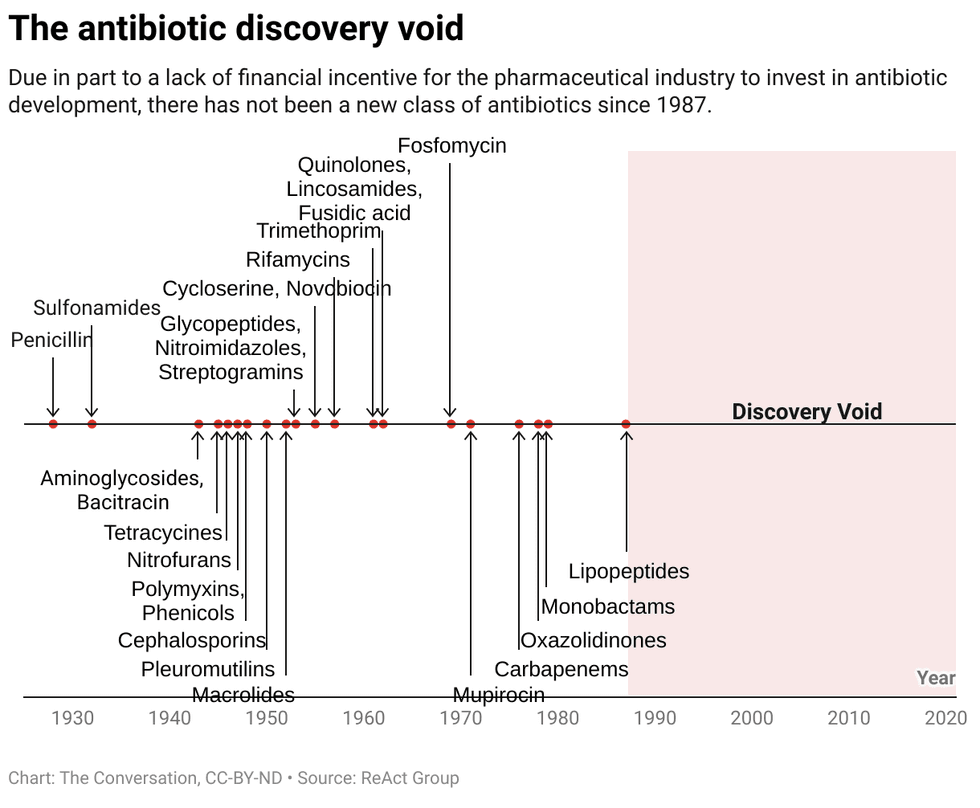

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.