It was a spring evening in 2011. I was sharing an inflatable mattress in the back of my friend’s truck. We were midway through Coachella when a group of Irish tourists car-camped in the plot behind us. To the right of our truck was an abandoned yellow Lamborghini (because that’s a practical desert wagon) and to our left, were Wes and Joey.

Joey was 24 and a total babe.

As the night wore on, and a series of flamboyant ravers in neon headdresses infiltrated our camp, I sunk deeper into Joey’s armpit nook. We shared a box of Cheez-its as life happened all around us. It was pure romance.

Then he leaned forward and offered me a cold one. I declined. He asked why, as if I’d answered incorrectly. That’s when I disclosed that I’m straight edge. He asked me to explain. Suddenly, everyone around us seemed to lean in.

I told them the simple version: I don’t drink, smoke, or do recreational drugs–for life, by choice.

“Straight edge” for me is about being fully conscious and aware in an existential sense. It’s become the core to my identity and a crux to why I act the way I act and why I believe in what I believe. It’s embedded in me in a way that there’s really no temptation, because then nothing would make sense.

There were oohs and ahhs all around our impromptu tailgate kickback. Then the awkwardness set in.

Hardcore History

Straight edge is a subculture of the hardcore punk scene that promotes clean living for a conscious lifestyle–self-avowed abstinence from alcohol, drugs, and tobacco for life.

There is no manifesto or uniform. Just a 46-second anthem titled “Straight Edge” written in 1981 by Minor Threat that goes a little something like this:

“I’m a person just like you, but I’ve got better things to do / than sit around and fuck my head, hang out with the living dead / snort white shit up my nose, pass out at the shows / I don’t even think about speed, that’s something I just don’t need / I’ve got the straight edge.”

Frontman Ian MacKaye didn’t intend for the international movement that ensued. He was just sick of watching his friends waste themselves.

“[In the ’70s] pretty much what I saw were just people getting high,” MacKaye said at the Library of Congress in 2013. “In high school, I loved all my friends, but so many of them were just partying. It was disappointing that that was the only form of rebellion that they could come up with, which was self-destruction.”

Mackaye and his band mates began to drag marker tips in an ‘X’ —a along the backs of their hands before gigs at alcohol-serving venues to be clear of their clean intentions. This common minor-marking system predated wristbands and was swiftly adopted by adherents of the movement.

“[Self-destruction] just seemed counterproductive to me,” he continued. “If you wanted to rebel against society, don’t dull the blade.”

Straight edge became the anti to the anti, providing uncompromising youth with a drug-free alternative. It exchanged punk’s seemingly mandatory inebriated self-abuse and contradictory participation in mainstream drug culture for clean living dosed in a PMA, or “positive mental attitude.” The “sxe” movement challenged punk ideology and, through its extreme approach, queried adult rites-of-passage en masse, asking the obvious question: Do we really need this stuff?

That resistance to the “supposed to’s” resonated with me. To rebel against the rebellion. To have the courage to really think for yourself. It was more punk than punk itself. Made sense to me. Others, however, struggle to see it that way.

X Marks The Spot

Every morning I double-stroked the fat, black Marks-A-Lot across the back of my left hand for school. A handful of kids actually followed me because “it looked cool,” quick to give it up until the next house party. The only other boy I knew to not sell out remains a close friend today. My mom was the “show mom” who drove the two of us to hardcore gigs in our Pasadena stomping grounds.

We weren’t in it to be cool. We weren’t in it for each other. We sought to be clean to think for ourselves as best we could in the hyper stimulated, media-centric Western world.

To us it was just a different path, the path less intoxicated.

One day when I showed up at school with an ‘X’ in black nail polish at the base of my thumb, a friend asked, “So, does this mean you’re straight edge now?” No, it didn’t. It couldn’t, because I had no idea what that was and if I did, I wasn’t even doing it right.

That year I would Google search the term and marry it a year later. I researched the Teen Idles turn to Minor Threat, MacKaye’s other projects like Dischord Records and Fugazi, Davey Havok’s personal journey to sobriety, the PM behind Bad Brains, and so on.

That year I would also experience a particularly dramatic run-in with my divorced parents that led me to a couple of attempted suicides. I was unwilling to talk about it and knew I needed a new hobby than offing myself.

But if we’re going to pinpoint a VH1 “that’s where it all changed” moment, it wasn’t the functioning alcoholic father or the overworked single mom or the preteen episodes of regained consciousness from bathroom-floor tiles. It was seeing my best friend cry with a terrifying scene straight out of an after-school special.

A Match Made in Tim Burton Hell

I was probably in my elastic-waisted red skirt on the walk home–a tribute to my scant femininity and body-image insecurities, hiding from pant sizes so I just wore skirts until my hips stopped shifting. By my side, Ashley’s dark, vinyl lips dripped from a Mac mask complete with the harshest onyx eyeliner only femme frontmen like Robert Smith or Marilyn Manson dared to draw on.

My stringy thrash-metal split ends. Her fishnets underlined by creepers. My TRIPP jacket. Her plaid bomber. We were a match made in Tim Burton’s hell. Actually, our mothers introduced us

We schlepped our way three long blocks to her house. Ashley (not her real name) lived in an upstairs apartment off of a main street in Temple City. We climbed that last step up at the top of the staircase. The door was unlocked. Her mother, Ellen (not her real name), was home.

The playful tone we walked home with didn’t follow us into the dead living room, it’s carpet now covered in eggshells.

Then, it clicks: My mother mentioned earlier in the week how customer complaints had sent Ellen home from work on counts of slurred speech and smelling like Jack Daniels.

Playing it cool, I tried to carry the afternoon despite my friend’s embarrassment and fear. She didn’t want me there, as a witness, but didn’t know how to ask me to leave.

About two hours into our hang-out-gone-awry, her mother barked from her room for Ashley’s bedside assistance. This would now happen every three or four minutes. With each exchange, my friend was being stripped of a wall she had carefully mortared.

Ellen wanted something. She grew more and more desperate.

“Do it. Do it or I’ll fucking kill you.”

My reflexes kicked in. I couldn’t stop shaking. I shouted, but my voice broke like a prepubescent boy reading out loud in class.

“You do not talk to her like that,” I said. “That’s my friend. I don’t care who you are.”

Ashley’s Mac mask, the one that lit up at our inside jokes and bottomless Spongebob references, was now smeared to ruin. Well-versed in self respect (thanks, Mom), I drew the line, but for a moment I was convinced that maybe I was the one who crossed it. Ashley didn’t want to leave, but I got us outside and phoned her aunt for rescue.

Later that night, my mom got Ellen into rehab. Ashley would sleep over a lot after that. Not once did we talk about that afternoon, which was fine. She was safe.

But these hours play out in a flash every time someone asks me why I chose straight edge.

The Isolation of a Sober Life

Joey would reject me that night in the desert valley. He said it was because I was “too innocent.” Not the first time I’ve gotten that.

I’ve never been drunk or high. My lack of temptation often instigates a challenge around hostile crowds. There’s always charming threats to get me “fucked up” or drug my drink when my guard is down. I’m often forced to repeat my beliefs, particularly at family gatherings with bets placed on when I’ll “grow out of it.”

Alcohol is so normalized in society that my identity as a straight edge is seen by skeptics as nothing but a laughable, interim phase. The danger here is that it’s actually socially-acceptable exclusion. The widespread rejection of me and my sober lifestyle feels like a soft discrimination in the otherwise progressive societies of modern day.

In this Twilight Zone episode that is my life, those under the influence label me as a judgmental prude in less than two minutes of meeting.

But I’m not the militant prick edger or the holier-than-thou pusher preaching conversion. If you ask, I’ll reply. The biggest bummer of it all is that my lack of participation tends to project others insecurities, avoided addictions, or self-judgements they may have onto me, regarding a lifestyle I chose for my individual self. It’s just easier for many to label me as a boring or naive person who is “going through a phase.” Go ahead, I’ve heard it all.

Those who stuck around into the third minute of this theoretical sobriety spiel have proven to be some of the most genuine humans I’m honored to have met. They don’t hesitate to hang out, knowing I can include myself in just about any situation. And to the handful that have trickled through my grasp due to frequenting other friend circles reliant to the bar crawl, I get it–it’s just easier.

As for me, to be my authentic self, I must be mindful in every given moment. I’m behind every decision I’m allowed to make, anticipating those with unfavorable ends, and I’m executing it to my best ability. It’s all me.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

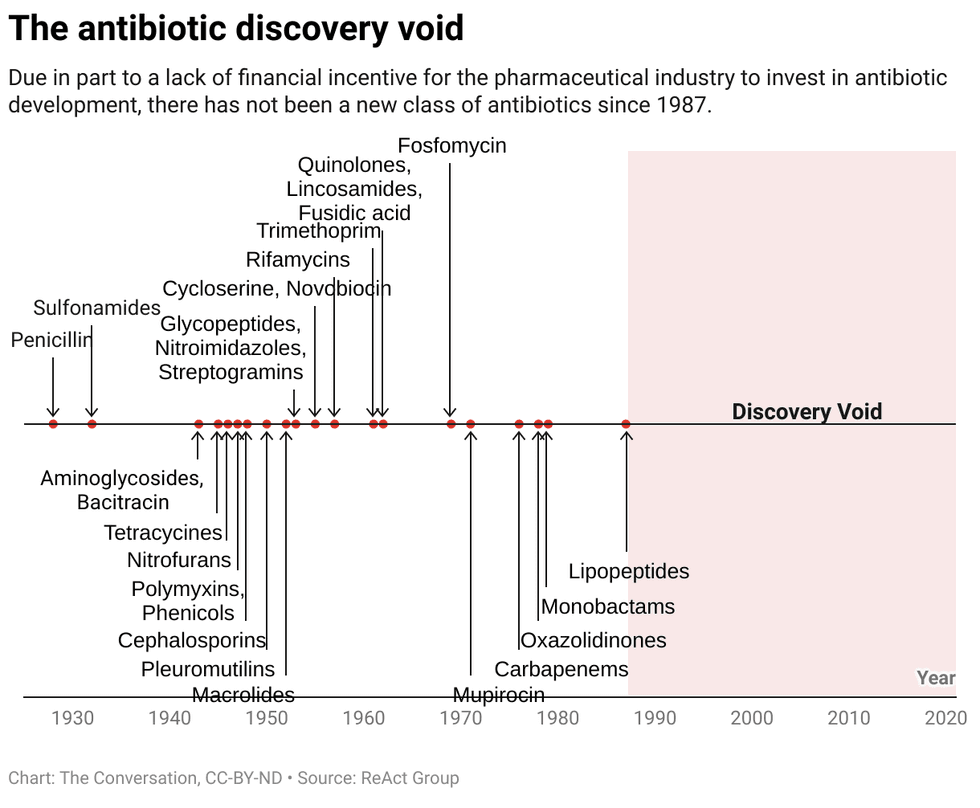

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.

Amoxicillin is a commonly prescribed broad-spectrum antibiotic.  Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Chart: The Conversation, CC-BY-ND

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:

Mushrooms containing psilocybin.Photo credit:  Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:

Woman undergoing cancer treatments looks out the window.Photo credit:  Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit:

Friend and patient on a walk.Photo credit: