When it comes to stopping the outbreak of a dangerous drug-resistant “superbug” bacteria, doctors often have to become detectives. They can treat each patient as they come in, but stopping the infection from spreading — that can be the key to saving even more lives.

Recently, a team at the University of Michigan and Rush University Medical Center used data from a real-world outbreak of a dangerous, drug-resistant superbug called CRKP to show that genetic testing can reveal how these superbugs are spreading, giving doctors a heads up on how to break the chain of infection and potentally stop an outbreak in its tracks.

The data from that CRKP outbreak provided researchers with the story of how the disease spread. In 2008, a man — who was incredibly sick and dying from a CRKP infection — was transferred to Rush University Medical Center in Chicago from a hospital in northern Indiana. Doctors there knew he wasn’t the first CRKP case in the Chicago area. Another case had cropped up just five months earlier.

Two cases of a dangerous superbug appearing in the same region had the doctors worried. A team headed by Mary Hayden, an infectious disease physician, began investigating. With a bit of legwork, they were able to find and map out the spread of the infection, watching how it hitched rides on dozens of different patients as they were transferred from hospital to hospital, nursing home to nursing home.

At the time, genetic analysis wasn’t sophisticated enough to really help Hayden track the chain of infection, but her team preserved samples from the patients anyway, hoping they could one day serve as time capsules for future investigations.

Now, they can.

The recent breakthrough involves whole genome sequencing. As bacteria grow and spread, they inevitably accumulate mutations in their genome, and by taking genetic samples from two different strains and comparing their unique mutations, scientists can tell if they’re related. It’s kind of like running a bacterial paternity test.

Hayden wanted to see if this kind of sequencing could have helped find the chain even faster during the 2008 outbreak.

To test her theory, she teamed up with Evan Snitkin’s genetics lab at the University of Michigan. Snitkin’s team tested each of Hayden’s samples in the order they were originally collected and without any prior information about each sample, essentially walking through the crisis beat-for-beat. As they did, they used the genome sequencing to build a kind of bacterial family tree.

When the two teams compared the new bacterial family tree with the results of Hayden’s 2008 investigation, they lined up nicely.

The technique won’t just duplicate conventional detective work, Hayden says. It could also help reveal nuances and insights into how a superbug is spreading, allowing doctors to move quickly to stop the chain of infection.

During the 2008 outbreak, for example, there were five patients, all at the same hospital, who had all caught CRKP. But doctors didn’t know how and when each patient picked up the bug. If one patient had carried it and spread it to all the others, for example, that’d mean the superbug was spreading within the hospital. On the other hand, if each patient had picked up the bug somewhere else and then came to the hospital, the source must be somewhere else.

Back then, the doctors had to work without knowing which scenario was true, but Hayden’s new genetic analysis showed that it had actually been a combination of both scenarios. Three of the patients contracted CRKP outside the hospital first, then two of them spread the bug to two other patients once they were hospitalized.

Had this technology been available at the time, doctors would have known as soon as they saw the test that they needed to do something to prevent transmission inside the hospital, such as isolating carriers and infected patients, as well as look for an outside source.

“The earlier we can intervene to contain an outbreak, the more likely it is that we can eradicate it," Hayden explained in a press release.

Drug-resistant bacteria like CRKP have become a major medical problem in the United States. At least 2 million Americans catch one of these infections each year and more than 20,000 die from one.

The team’s process will still need to be tested in other settings, like nursing homes and with other diseases, says Hayden, but it should work with nonbacterial infections, such as those caused by viruses and fungi, and could provide a powerful complement to standard epidemiological detective work. The team’s work appeared in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

The team isn’t the only lab that has this kind of equipment and capability, and as such, they’re hoping their results can serve as a proof of concept for doctors and public health agencies like the CDC.

When outbreaks happen, doctors have to become detectives. Thanks to tools like this, the medical Moriarty that is superbug outbreaks may soon be easier than ever to defeat.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

Revenge can feel easier than forgiveness, which often brings sadness or anxiety.

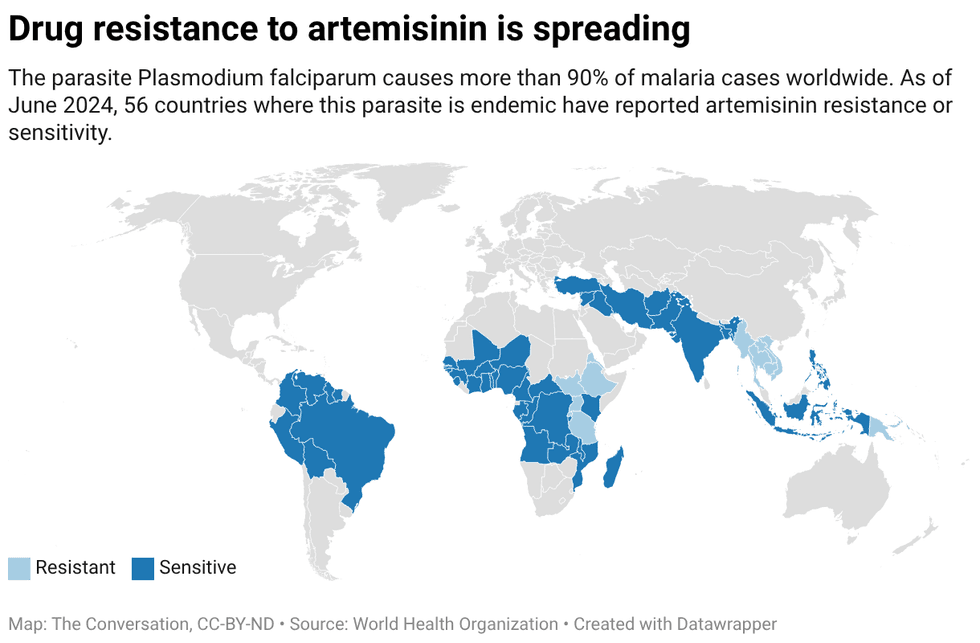

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age.

In the past two years, two malaria vaccines have become available for babies starting at 5 months of age. By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells.

By exploiting vulnerabilities in the malaria parasite’s defense system, researchers hope to develop a treatment that blocks the parasite from entering cells. Created with

Created with

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Volunteers who drive homeless people to shelters talk with a person from Ukraine in Berlin on Jan. 7, 2026.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health.

Tasks that stretch your brain just beyond its comfort zone, such as knitting and crocheting, can improve cognitive abilities over your lifespan – and doing them in a group setting brings an additional bonus for overall health. Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Overdoing any task, whether it be weight training or sitting at the computer for too long, can overtax the muscles as well as the brain.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely.

Counterintuitively, social media can make you feel more bored and lonely. Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Talking about what you’ve read can add a social dimension to what can be a solitary activity.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.

Women and people of color who experience cardiac arrest are less likely to receive CPR.